Use AI to understand the Don Lemon prosecution

Former CNN anchor Don Lemon was arrested and federally indicted earlier this week for allegedly violating the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act in connection with an anti-ICE protest that disrupted a church service. A federal grand jury in the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota returned the indictment on January 29, 2026, charging Lemon and eight co-defendants with one count of conspiracy against rights (18 U.S.C. § 241) and one count of injuring, intimidating, or interfering with the exercise of religious freedom at a place of worship under the FACE Act (18 U.S.C. § 248). The U.S. Department of Justice, under Attorney General Pam Bondi, brought the charges, with involvement from the FBI and Homeland Security Investigations. It did so after a federal magistrate had refused to issue an arrest warrant against Mr. Lemon.

Lemon was arrested late on January 29, 2026, by federal agents in Los Angeles, California, while covering the Grammy Awards. He appeared in federal court in Los Angeles the following day and was released on his own recognizance without bond.

If convicted, penalties under the FACE Act for a first-time offense include fines and up to one year in prison (or six months for nonviolent physical obstruction); subsequent offenses carry up to three years. The conspiracy charge under § 241 is more serious. It can carry up to 10 years if no aggravating factors like bodily injury apply. Lemon, now an independent journalist, has vowed to fight the charges, with press freedom advocates decrying potential First Amendment implications.

That's the news. My social media feeds are full of outrage over this prosecution. But what is the law here? And, more to the point, how can AI help us understand the prosecution? This is the story of how I used AI – the combination of Claude Cowork and midpage.ai I described in a previous blog post – to produce an 196-page grounded briefing book in a morning. It educates readers about the conflict between the first amendment freedoms of Mr. Lemon and the first amendment freedoms of worshippers at the church whose services were disrupted as well as the property interests of the church. The briefing book contains a legal memo discussing journalist liability, 18 case briefs providing detailed information on each of the cases described in the memo, and several "statute briefs" giving additional information on statutes that Mr. Lemon may have violated. That briefing book proved the predicate for a NotebookLM site that has in turn produced video presentations, an audio debate, and other materials that should prove useful to those concerned about constitutional liberties.

Here is a copy of the briefing book as a PDF file.

Here's an AI-generated ~600-word summary of the far-longer briefing book.

The Constitutional Framework: What the Law Actually Says

The First Amendment robustly protects the publication of news, but it confers no special privilege to gather it. This distinction, established in Branzburg v. Hayes (1972) and consistently reaffirmed, means journalists enjoy no immunity from generally applicable laws. A reporter who trespasses, obstructs, or conspires is as liable as any other citizen who does the same.

The Newsgathering Doctrine in Brief

The Supreme Court has never recognized a constitutional right of access for the press beyond what the public enjoys. In Houchins v. KQED (1978), the Court held that "the First Amendment does not guarantee the press a constitutional right of special access to information not available to the public generally." This principle extends to private property: consent to enter can be revoked, and exceeding the scope of permission converts a lawful presence into trespass. Courts in Dietemann v. Time, Miller v. NBC, and numerous other cases have held journalists liable when their conduct—hidden cameras, deception, or overstaying welcome—exceeded what their initial access permitted.

The FACE Act: Protecting Religious Worship

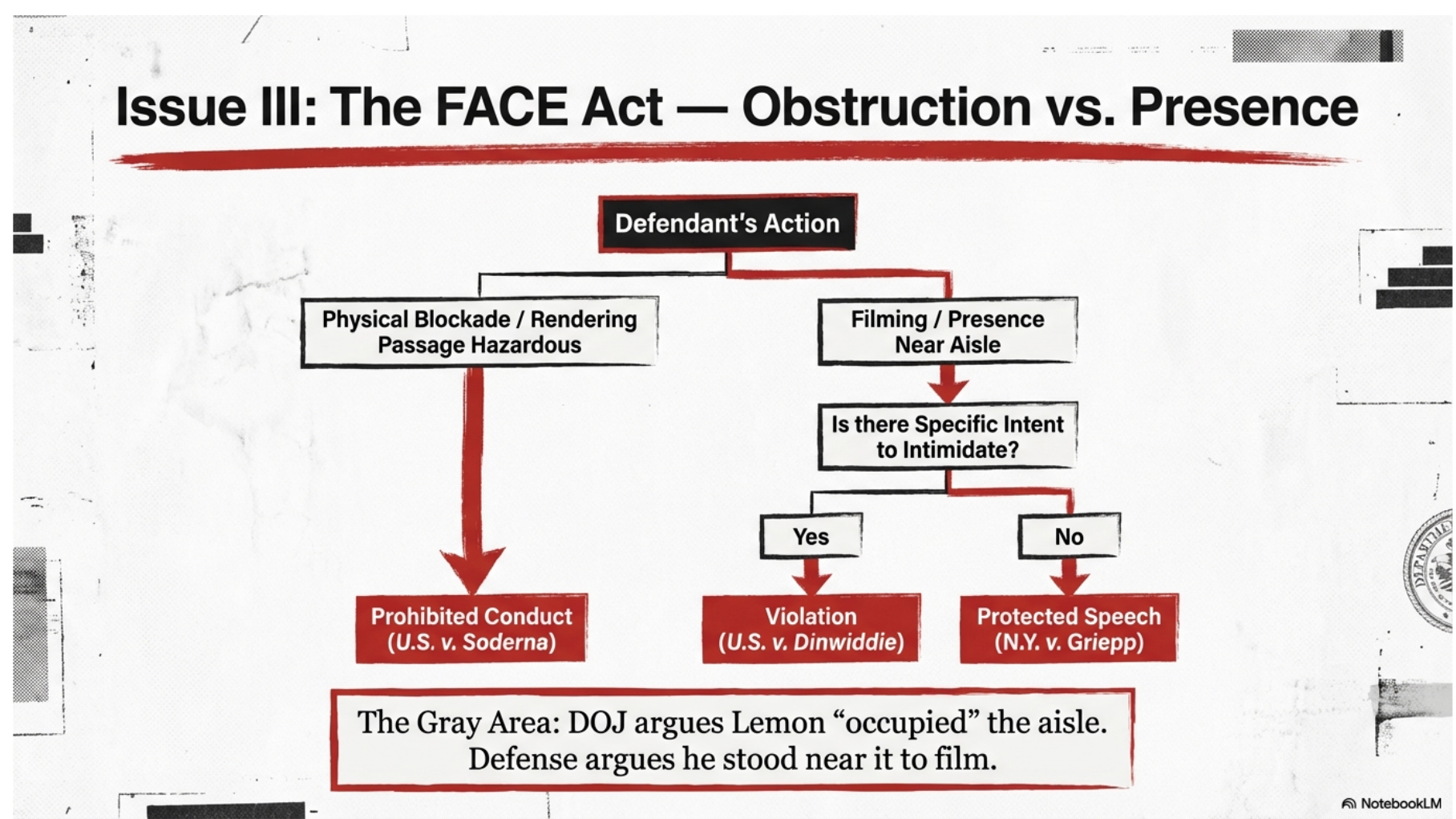

The Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (18 U.S.C. § 248) protects not only reproductive health facilities but also "places of religious worship." It prohibits using force, threat of force, or physical obstruction to intentionally injure, intimidate, or interfere with persons obtaining or providing religious services.

"Physical obstruction" under FACE means "rendering impassable ingress to or egress from a facility" or "rendering passage to or from such a facility unreasonably difficult or hazardous." Courts have interpreted this to include human blockades, locked arms, and coordinated interference—but the statute requires more than mere presence. The government must prove the defendant intended both to obstruct and to interfere with the exercise of religious rights.

Section 241: Conspiracy Against Rights

The companion charge, 18 U.S.C. § 241, criminalizes conspiracy to "injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate" any person in the free exercise of constitutional or federal rights. Conviction requires proof of: (1) an agreement between two or more persons; (2) to injure or intimidate someone in the exercise of a federal right; and (3) an overt act by at least one conspirator. Critically, the defendant must have specific intent to deprive the victim of a known federal right—not merely general awareness that disruption might occur.

Where the Line Falls

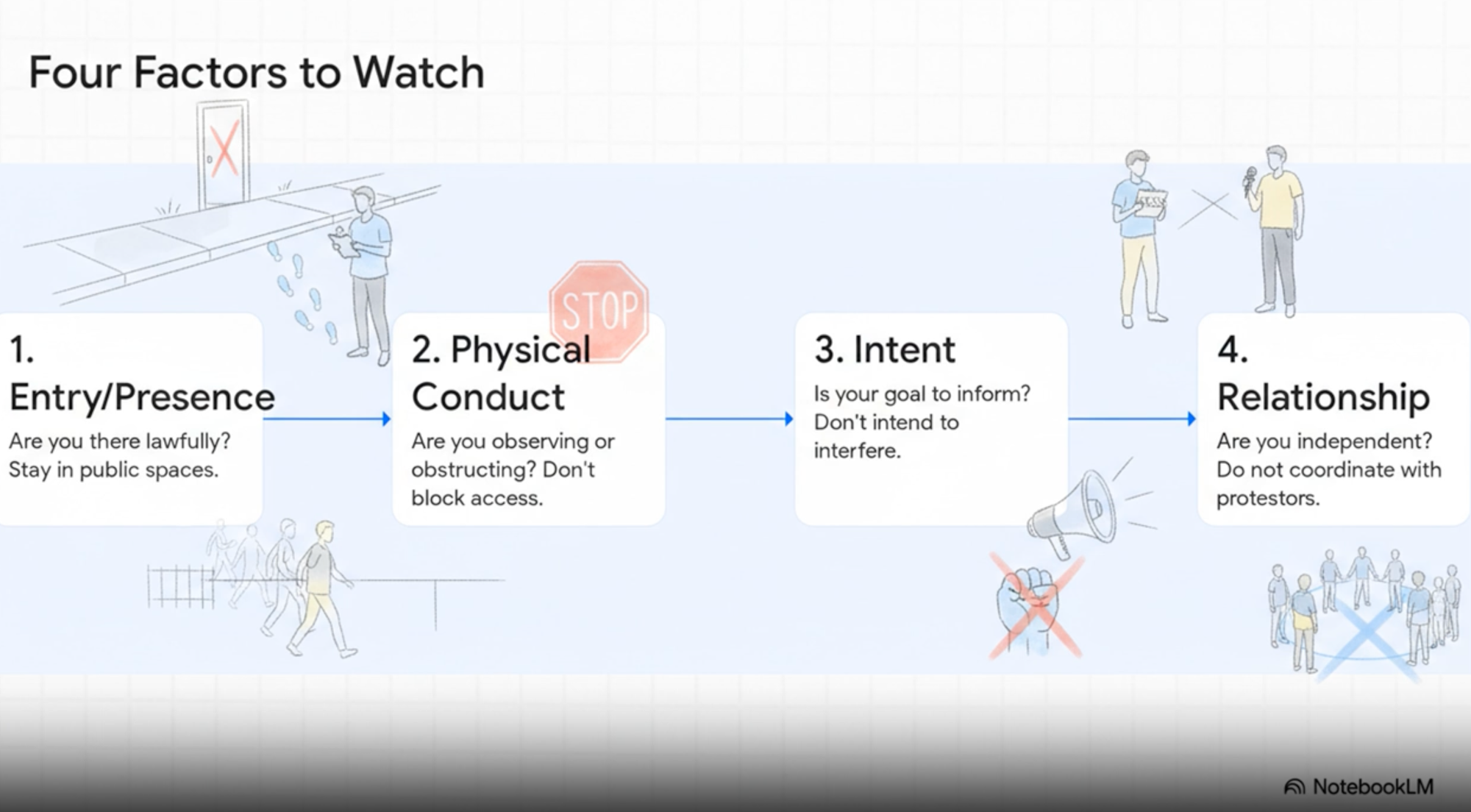

The legal question in any journalist prosecution under these statutes is whether the individual crossed from observer to participant. Mere presence at a protest—even an unlawful one—does not establish conspiracy. The government must prove the journalist agreed to the obstruction and took some act in furtherance of that agreement.

This is fact-intensive terrain. Did the journalist enter with permission or as part of a coordinated trespass? Did they merely document events, or did their physical position contribute to blocking access? Did they have advance knowledge of and agreement to the unlawful plan?

The Constitutional Tension

Both sides in this debate have legitimate stakes. Journalists serve democracy by documenting government action and civil unrest—including inside churches where federal enforcement occurs. But worshippers have a federal statutory right to access their place of worship free from physical obstruction and intimidation.

The FACE Act and Section 241 are content-neutral; they regulate conduct, not speech. A journalist who physically blocks a church door while recording is not prosecuted for the recording but for the blocking. The Constitution permits this distinction.

The hard cases arise in the middle: journalists embedded with protesters, whose presence may inadvertently contribute to obstruction, or who receive advance notice of planned disruptions. Here, intent and agreement become dispositive—and notoriously difficult to prove beyond a reasonable doubt.

What emerges from the case law is not a bright line but a functional test: the press may observe and report, but it may not participate in the unlawful conduct it covers.

AI thus suggests that the issues are more complex than advocates on either side are asserting. Before those strongly opposed to the Trump administration's abuses in connection with Operation Metro Surge and to its anti-immigrant policies evangelize the Don-Lemon-as-victim-of-fascism narrative, they ought to think about the legal issues more carefully. The short version is that, although I do not think it likely that Mr. Lemon had the intent necessary to have violated the FACE Act, advocates need to take a more nuanced view of the constitutional issues involved. How would those advocates feel if MAGA zealots accompanied or possibly egged on by right-wing journalists invaded the services of a liberal church extolling the virtues of tolerance and support to immigrants? How would they feel if a similar journalist-augmented gang invaded their home or secular organization where a meeting organizing protests was occurring?

But intellectual honesty requires acknowledging the powerful counterarguments. Two federal judges independently reviewed the evidence against Lemon and found it wanting. Magistrate Judge Douglas Micko refused to sign arrest warrants for Lemon and four others, finding no probable cause — and notably crossed off the FACE Act charge even against actual protesters, writing "NO PROBABLE CAUSE" in the margin. Chief U.S. District Judge Patrick Schiltz went further, writing to the Eighth Circuit that Lemon and his producer were "not protesters at all" and that "[t]here is no evidence that those two engaged in any criminal behavior or conspired to do so." The Eighth Circuit declined to overrule these decisions. The government's response was not to accept the judiciary's assessment but to circumvent it by empaneling a grand jury — a body that hears only the prosecution's evidence and is somewhat facetiously stated to be ready to indict a ham sandwich. When Attorney General Bondi was reportedly "enraged" by the magistrate's decision, and when Assistant Attorney General Dhillon publicly warned Lemon he was "on notice" during a podcast appearance rather than in a court filing, reasonable people can question whether the prosecution reflects a good-faith application of the FACE Act or a politically motivated use of legal machinery against a prominent administration critic.

Moreover, the indictment's own theory should trouble anyone who cares about press freedom regardless of political alignment. The government's evidence against Lemon appears to rest substantially on his own journalism — his livestream video, his narration of what protesters were doing, his presence at a pre-protest gathering he was covering as a reporter. Journalists routinely receive advance notice of planned protests and show up at staging areas; that is called sourcing, not conspiracy. The legal framework I have described above correctly states that journalists who cross from observer to participant enjoy no special immunity. But the factual question — whether Lemon actually crossed that line — is one that two federal judges answered in the negative, and the chilling implications of the government's contrary theory extend well beyond this case. If describing a protest's purpose on a livestream or attending a staging area can supply the intent element of a federal conspiracy charge, embedded war correspondents and beat reporters covering civil disobedience everywhere should take notice.

But, as this a blog about AI in legal education, let me now get beyond the immediate issues of Don Lemon and talk about the methodology. How can you make your own briefing books on legal issues that you care about? My journey began with a general purpose AI. I asked it a series of questions about what had happened that precipitated Mr. Lemon's arrest, whether his actions might have constituted trespass under state law, and ultimately asked it to write up the legal question I might pose to a grounded AI that would have access to actual case law. I got a lengthy memo, but here is the first paragraph, which is what I ultimately used.

The core legal question is: Under the First Amendment and generally applicable federal and state laws—including criminal and civil trespass statutes, disorderly conduct laws, and the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act (18 U.S.C. § 248), which protects access to places of worship—when does a journalist who enters private property (such as a church during a worship service) to observe, livestream, interview, or report on a group protest or demonstration that itself involves unlawful entry, disruption, intimidation, obstruction, or interference with others' religious exercise cross into personal civil or criminal liability for trespass, aiding/abetting unlawful conduct, interference with protected rights, or conspiracy against rights (e.g., 18 U.S.C. § 241), rather than enjoying protection for newsgathering activities?

Midpage

I then fed the output from this general purpose AI into midpage.ai, a legal research AI that has access to legal texts and can draft responses to legal questions. After 90 seconds of thinking, midpage came back with the 3,000-word essay you see atop the briefing book. Here's an excerpt. You can see that it is full of properly cited legal authorities. In the original midpage version, these authorities are actually linked to their full text.

FIRST AMENDMENT, NEWSGATHERING, TRESPASS, FACE ACT, AND SECTION 241 CONSPIRACY: A LEGAL FRAMEWORK

MEMORANDUM

At a high level, the First Amendment protects the publication of news and, to a lesser extent, the act of gathering it—but it does not give journalists a license to trespass, obstruct access to religious worship, or join in a conspiracy to deprive others of federal rights. Liability turns on three things: (1) whether the journalist's physical presence or entry is authorized, (2) whether their conduct goes beyond observation into obstruction/intimidation or active facilitation, and (3) their intent and agreements with others.

Below is a framework keyed to the authorities you flagged.

1. Baseline First Amendment / Newsgathering Rules

The Supreme Court has been clear that the press enjoys no special immunity from laws of general application.

The Court has repeatedly held that generally applicable laws—contract, tort, trespass, tax, antitrust, etc.—apply to the press as they do to everyone else, and the First Amendment does not confer a special exemption simply because conduct is undertaken for newsgathering. Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972 U.S. LEXIS 132 (1972); Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 111 S. Ct. 2513 (1991). In Cohen, the Court emphasized that the press has "no special immunity" from laws of general applicability such as promissory estoppel; the fact that a promise was made in the course of journalism did not bar liability. Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 111 S. Ct. 2513 (1991).

Likewise, the Court has made clear that neither the public nor the press has a constitutional right of special access to private property or to information in government control beyond what is available to the public generally. Houchins v. KQED, Inc., 438 U.S. 1 (1978); Branzburg v. Hayes, 1972 U.S. LEXIS 132 (1972). That principle applies a fortiori to a privately owned church: there is no First Amendment right for press or public to enter or remain on church property when the church withholds or revokes consent.

Lower courts have articulated the corollary rule in the newsgathering context: "the First Amendment is not a license to trespass or to intrude by electronic means into the precincts of another's home or office," and does not immunize crimes or torts committed during newsgathering. A. A. Dietemann v. Time, Inc., 449 F.2d 245 (9th Cir. 1971); Ronald E. Galella v. Jacqueline Onassis, 487 F.2d 986 (2d Cir. 1973).

So the baseline: journalists have robust protection in publishing what they lawfully learn and in using "routine reporting techniques" such as asking questions, but no special privilege to invade private property, obstruct access, or join a criminal scheme. Nicholson v. McClatchy Newspapers, 177 Cal. App. 3d 509 (Cal. Ct. App. 1986); Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 111 S. Ct. 2513 (1991).

Claude Cowork

I then fed the entire memo to Claude Cowork and gave that new fantastic AI-variant the following prompt.

For each case (and particularly for each link provided) track down the case and provide a legal brief of that case as a part of the appendix. Use my case-briefing-skill to create the brief. Your ultimate output is a markdown file that has the original memo and an appendix with briefs for each of the cases. each brief should start on a new page. Also, save each brief to a file as we move along so that if there are problems we do not lose saved work and can pick up where we left off. Report each time you have finished briefing a case.

Case briefs

The referenced case-briefing skill is a Claude skill I had earlier developed (with Claude's assistance) and is based on work I did more than a year ago in creating a CustomGPT to brief cases. Here's the skill for those who want to deploy it. (Nothing is too good for my devoted readers). Once given the above directive, Claude Cowork proceeded diligently to do what generic AI is completely unable to do. It worked for over an hour to track down all 18 cases referenced in midpage's legal memo, brief them according to my specifications, and append the results to an ever-growing markdown file. Claude Cowork sometimes researched cases in parallel and was smart enough to save interim versions of its activities and to smoothly transition between sessions when the work outgrew its context limit. Here's an excerpt from a sample case brief.

Case Brief: Anderson v. WROC-TV, 109 Misc. 2d 904 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1981)

1. Memory Jogger

Television journalists who enter a private home without the owner's express consent cannot claim implied consent or First Amendment protection from trespass liability, even when accompanying law enforcement during a lawful search warrant execution.

2. Detailed Case Facts

Key Facts:

- On September 9, 1980, an investigator employed by the Humane Society of Rochester and Monroe County obtained a search warrant and conducted an investigation at 89 Arch Street in Rochester, New York.

- The investigator contacted three television stations—WROC-TV, WHEC-TV, and WOKR-TV—informing them of the impending search and inviting them to send newscasters and photographers to accompany him.

- Television photographers and reporters from WROC-TV and WOKR-TV responded to the invitation and accompanied the investigator into the plaintiffs' home.

- Plaintiff Joy E. Brenon expressly asked the television people to stay out of her house, but they entered notwithstanding her explicit instructions.

- The television crews filmed the interior of the home, and the story was subsequently broadcast on the evening news shows of WROC-TV and WOKR-TV.

- The plaintiffs sought damages against: (1) Ronald Storm (the Humane Society investigator) and the Humane Society for abuse of the search warrant and unlawful taking of property; (2) WROC-TV, WOKR-TV, WHEC-TV and their named individual employees for trespass.

Relevant Constitutional Provisions:

- First Amendment (freedom of speech and press; right to gather news)

- Fourth Amendment (unreasonable searches and seizures; limits on search warrant execution)

- Common law property rights and tort law (trespass)

Statute briefs

With that done, I then told Claude Cowork to go back through the midpage document and create briefs of the statutes that midpage referenced, using my statute-briefing skill to do so. It took about 10 minutes to produce the additional material.

And here's a sample from a "statute brief."

RULES: 18 U.S.C. § 248 (FACE Act)

Rule-Module: § 248(a)(2) — Prohibition on Force/Obstruction at Places of Religious Worship

1. Provision

18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(2)

2. Trigger conditions (elements)

- Means: The defendant acted "by force or threat of force or by physical obstruction"

- Mental state: The defendant "intentionally injures, intimidates or interferes with or attempts to" do so

- Protected person: The victim is "any person lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom"

- Location: The conduct occurs "at a place of religious worship"

- Dual intent (judicially implied): The defendant acts (a) with intent to injure/intimidate/interfere, and (b) because of the victim's exercise or anticipated exercise of religious worship rights

3. Legal effect

Prohibition: Criminalizes the use of force, threats, or physical obstruction to intentionally injure, intimidate, or interfere with persons exercising religious freedom at a place of worship.

Entitlement: Creates a private cause of action and authorizes Attorney General civil enforcement.

4. Exceptions / defenses / safe harbors

- First Amendment safe harbor: "Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit any expressive conduct (including peaceful picketing or other peaceful demonstration) protected from legal prohibition by the First Amendment to the Constitution." — § 248(d)(1)

- No intent to obstruct/intimidate: If defendant's purpose is documentation, self-protection, or observation—rather than injury, intimidation, or interference—the dual intent requirement is not satisfied.

5. Procedure / decision-maker

- Criminal: Prosecuted by United States Attorney in federal district court

- Civil (private): Action may be brought by "a person lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship or by the entity that owns or operates such place of religious worship" — § 248(c)(1)(A)

- Civil (government): Attorney General may commence action upon "reasonable cause to believe that any person or group of persons is being, has been, or may be injured" — § 248(c)(2)(A)

- Standard: Criminal: proof beyond reasonable doubt; Civil: preponderance of the evidence

6. Consequences

Criminal penalties (§ 248(b)):

| Offense Type | First Offense | Subsequent Offense |

|---|---|---|

| General | Fine and/or ≤ 1 year imprisonment | Fine and/or ≤ 3 years imprisonment |

| Nonviolent physical obstruction only | Fine ≤ $10,000 and/or ≤ 6 months | Fine ≤ $25,000 and/or ≤ 18 months |

| Bodily injury results | Fine and/or ≤ 10 years | Fine and/or ≤ 10 years |

| Death results | Fine and/or any term of years or life | Fine and/or any term of years or life |

The result of both of these processes, as mentioned, is an almost 200-page work giving a very complete analysis of the legal issues and case and statutory authorities involved. This is work that would have taken a trained human at least 10 hours. It's also the sort of thing that even the best large language models could not do several months ago without someone skilled in writing API calls. Legal educators need to realize that the AI landscape has changed yet again. Now, the average person without programming skills can call on AIs such as Claude Cowork to undertake massive and sophisticated sustained tasks and produce legal outputs grounded not in mere training data but in the actual text of cases and statutes.

NotebookLM

But ... Claude Cowork may have been too thorough. How many of us are really going to read through 200 pages to figure out the extent to which federal prosecutors may have overstepped? Enter NotebookLM, still the best general purpose AI tool for legal education. It is a master at digesting and repackaging materials. I fed it the 200 pages and then added in some sources on the actual arrest of Don Lemon. Here's a link to the result.

Set forth below are some of the artifacts it produced. One of the lovely things about NotebookLM is that you can take it, add your own sources, and produce your own artifacts.

Here's a debate about the constitutionality of the arrest of Mr. Lemon.

Here's a slide presentation created by NotebookLM from the lengthy grounded materials I provided to it. I append a screen capture of one of the slides.

And a six-minute video podcast of the issues involved.

The Big Picture

As with many of my blog entries, I have two purposes here. The first is to explicate a legal event of significance. A federal executive seeking to imprison people exercising legitimate first amendment rights of free speech is a terrifying prospect. It is all the more terrifying when that same federal executive seems to be imprisoning people – even 5 year olds – without lawful cause. But it is equally dangerous to place beyond legal challenge the invasion of private property — and, a fortiori, a place of worship — by people who disagree with the church's actions or positions. No true liberal should condone the latter actions. Invading a church because you think the pastor is evil is as problematic as invading a private home of a law school dean because you happen to disagree with the dean's stance on on the October 7 war or its aftermath. Journalists wanting the shield of the first amendment need to be very careful that they are at most covering the news, not creating it and not augmeting violations of others' rights. Maybe it's a bit unfair that wealth and property can buy constitutional protection from the mob, but the alternative is far worse.

My second purpose, however, is again to show how modern AI can spectacularly reduce the cost of legal scholarship to the point that activities that would otherwise never be contemplated (unless a lot of money was involved) now become eminently doable. The democratization of rigorous legal analysis is no longer aspirational; it is, as this exercise demonstrates, already here for anyone willing to explore the ever-simpler tools.