Why I Learned Linux (and What It Taught Me About Systems, Teaching, and Control)

I did not come to Linux because I hated Apple or Microsoft. Let’s get that out of the way early. In fact, I like Apple hardware quite a lot. I’ve used Macs for years. I’ve also lived in Windows land for enough periods of my life to know my way around it without flinching. This was not a rage-quit situation or even a quit situation at all. This was curiosity—the slow-burn, slightly nerdy, why-does-the-world-work-like-this kind.

The initial thought was simple: if the world’s biggest, most important computers run Linux, maybe I should understand it. Not at the “open a terminal and feel powerful” level, but at the deeper level where you understand what’s actually happening underneath the shiny user interface.

There was also a practical angle. macOS is, at heart, a Unix-like system. Linux, which likewise descends from Unix, isn’t macOS, but it’s family. Learning Linux felt like learning the backend of my own machine—like discovering that the pleasant restaurant I enjoy eating at also has a fascinating, noisy, slightly chaotic kitchen behind it. Also, since most of the work I am doing in AI relies on Cloud Computing anyway with a browser interface, what could really be lost by a dalliance with Linux.

I had no idea that this innocent curiosity would lead me to:

- buying nine computers for under $1,500 total,

- learning more acronyms than I thought a human brain should contain,

- yelling at Wi-Fi drivers at 2 a.m.,

- developing opinions about window managers (this happens to people),

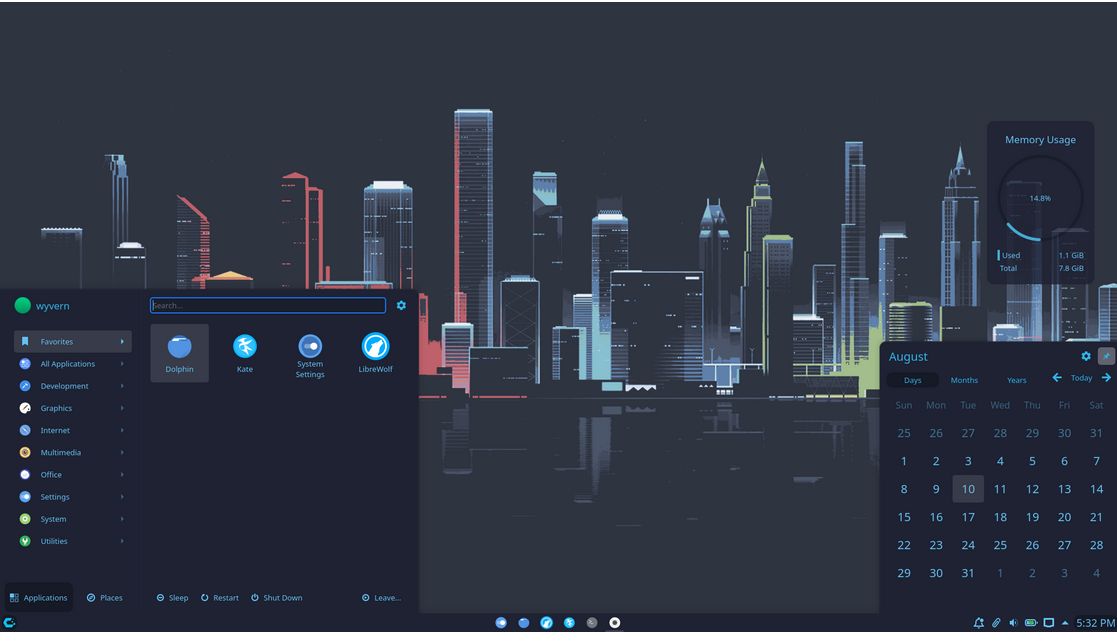

- and eventually building a reproducible Linux system that can boot into Plasma, Cinnamon, Xfce, Hyprland, or COSMIC on demand. (If you don't know what these are just feign awe).

This is that story. I know it isn't for every reader of legaled.ai, and maybe it isn't completely on point, but I have to get it off my chest.

Phase 1: The Terminal and the Illusion of Competence

Like many people, my Linux journey began with the terminal.

There’s a very specific dopamine hit that comes from typing ls and seeing files scroll by. It feels like you’ve unlocked something secret, even though you’ve really just asked the computer to list things. Then comes cd, and suddenly you’re moving through space. cat lets you read files as if you’re peeking behind the curtain. Magic.

At this stage, Linux feels clean. Honest. Slightly austere, but in a good way. And not even that hard. Plus, no popups. No nags. No operating system trying to save you from yourself like a helicopter parent. Talking about you, Windows. Moreover, with mid 2020s AI you don't have to learn or remember how to find a list of the device drivers for your wifi or execute other commands. Any decent AI will give you a good answer and if you install Warp Terminal, you can even have it guide you as the terminal. (lspci -k | grep -A 3 -i "network", for the curious).

Of course, this is also the stage where you begin to realize how just much you don’t understand. ChatGPT 5.2, which helped me sculpt this blog entry from a stream-of-consciousness dump, suggested at this point that I should write "This phase is pure joy, and everyone should get to experience it at least once." No! This phase is hardly pure joy. It is a mixture of every emotion under the planet. Joy, frustration, rage. The secret, I discovered, was knowing when to call it a night and to start fresh in the morning.

Phase 2: Distros, Distros Everywhere

Then you discover distributions.

At first, this seems reasonable. Linux is just the kernel; distros package it in different ways. Fair enough. But then you realize there are hundreds of them. And people have opinions – opinions that end up littering YouTube and other fora with thousands and thousands of postings. Do not inquire into how many of them I have examined.

Arch users will tell you that everything else is training wheels. (I sometimes use Arch, BTW). Debian users will explain stability with monk-like patience. Ubuntu users will say “it just works” (sometimes defensively). Fedora users will talk about “upstream” and “modern kernels.” Someone will inevitably recommend Gentoo, which is the Linux equivalent of suggesting that someone learn to swim by crossing the English Channel.

This is where most beginners get bad advice. I too now have a strong opinion with which I will now litter the internet. If you are beginning there is only one good choice. Well, maybe two. You should use Linux Mint. Not because it’s flashy. Not because it’s cool. But because it works.

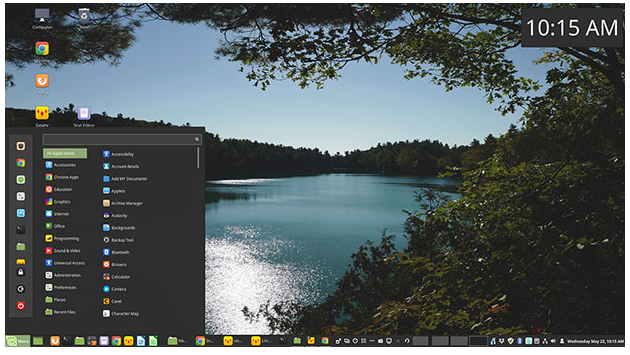

Mint installs cleanly. Unlike its parent Ubuntu, it handles non-standard Wi-Fi hardware and drivers (like the sort Apple puts on its laptops or the 2013 "trash can" Mac Pro that was my starter Linux machine) better than almost anything else. The prodigal child Mint took five minutes to conquer what had taken at least 10 hours to get working on the Ubuntu distribution that the Interweb had suggested as my starter distro. Mint doesn’t assume you want to become a part-time system administrator. And — this matters — its "Cinnamon" desktop feels familiar to both Mac and Windows users. Mint is Linux without the hazing ritual.

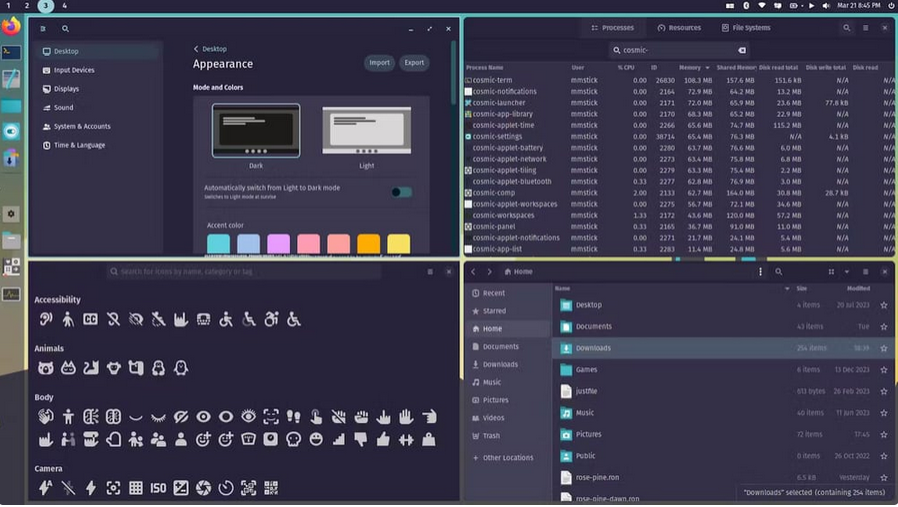

I mentioned, however, that there might be a second right answer for beginners. Indeed, I suspect that in six months it will be the better answer. It is Cosmic from Pop!_OS (a name that reads like a password). When my Linux journey began, that distribution was in beta. Indeed, if you speak to large language models about Cosmic, they will often dismiss it as some risky thing still in alpha. That's the sort of hallucination that comes from relying on 2024 or early 2025 training data that, in the world of computers, is grotesquely outdated. And it leads to bad advice. Perhaps a year ago, Cosmic was at the frontier. Not today. A few weeks ago, it emerged out of beta into the world as something real.

Cosmic is thoughtfully designed, and modern without being alien. It has lovely tiling windows, which enhances productivity on laptops by automatically organizing windows into non-overlapping tiles that maximize limited screen real estate, while enabling lightning-fast keyboard-driven navigation and switching that eliminates the need to constantly reach for the trackpad or mouse. Great for couch computing if nothing else. Indeed, I am using Cosmic right now (well, Cosmic desktop over NixOS) as I write this blog entry moving among couch, kitchen counter and office.

The Big Realization: Decomposition

But here’s the important part: if you know what you’re doing, you don’t have to choose between Mint or Cosmic. What we think of as an “operating system” like macOS or Windows is actually a composite of several layers:

- Base functionality (kernel, core utilities)

- Software provisioning (what apps come with the system, how you install more)

- Window management, and

- Compositing and desktop environment

MacOS and Windows tightly bundle these layers so that they seem seamless. Linux – or least some Linux distributions – do not.

This decomposition is both Linux’s greatest strength and its greatest source of confusion. Once you understand that you can mix and match these layers—swap desktop environments, change window managers, replace software provisioning system, Linux suddenly makes sense. Before that, it feels like a maze of arbitrary choices. With a little bit of up front effort, now, you can seemlessly shift between Cinnamon (Mint’s desktop), Cosmic or other front ends (Hyprland, Xfce) without committing to their full distros. That's the beauty of free and open-source software and of decomposing the unified operating system presented by Microsoft and Apple into modular parts.

This realization took me a long time. And most online advice assumes you already understand it, which is why it’s so often unhelpful. BTW if I need a flimsy excuse for how my Linux education relates to my day job, it is that learning something new and difficult makes you a better teacher – or at least it should. It teaches you not to make assumptions, how to embrace transitory oversimplifications, and how to build up from there. More importantly, it boosts EQ by teaching patience, resilience, persistence, and humility. Maybe that isn't so flimsy after all.

The Arch Linux Phase (a.k.a. “I Almost Stayed Here”)

Most Linux users—especially those caught in the self-reinforcing YouTube recommendation algorithm—eventually fall victim to "the grass is always greener" syndrome. I was no exception. Despite having built a perfectly happy home on Mint, I felt the itch for adventure. That led me into an Arch Linux phase. By the way, I'm still in it.

Arch is minimal in the same way a well-designed workshop is minimal: nothing extra, everything intentional. You install only what you need. It forces you to understand your system because there’s nothing obscuring the details.

The ecosystem is equally impressive. Pacman is fast, simple, and a joy to use; I don't have a sudo pacman -Syu tee-shirt yet, but I probably should update my wardrobe with one. Between the native repositories and the astonishing Arch User Repository (AUR), if a piece of software exists, it’s available.

However, you don't have to build from vanilla Arch to get these benefits. Many distributions use Arch as a high-performance foundation. Enter CachyOS. It takes the Arch base and adds a curated software suite and a polished installer for various desktop environments. Most impressively, it squeezes extra performance out of your hardware by using a custom-tuned kernel and packages compiled specifically for modern CPUs. It’s Arch, but with the turbocharger already bolted on. I'm not a gamer, but if I were the case for CachyOS becomes even stronger. All of this is probably why CachyOS has been number one on the Linux hit site "DistroWatch" for the past year. (Mint is second; NixOS (more later) is a respectable number 15).

Cheap Computers and the Joy of Resurrection

At some point, my Linux journey intersected with eBay.

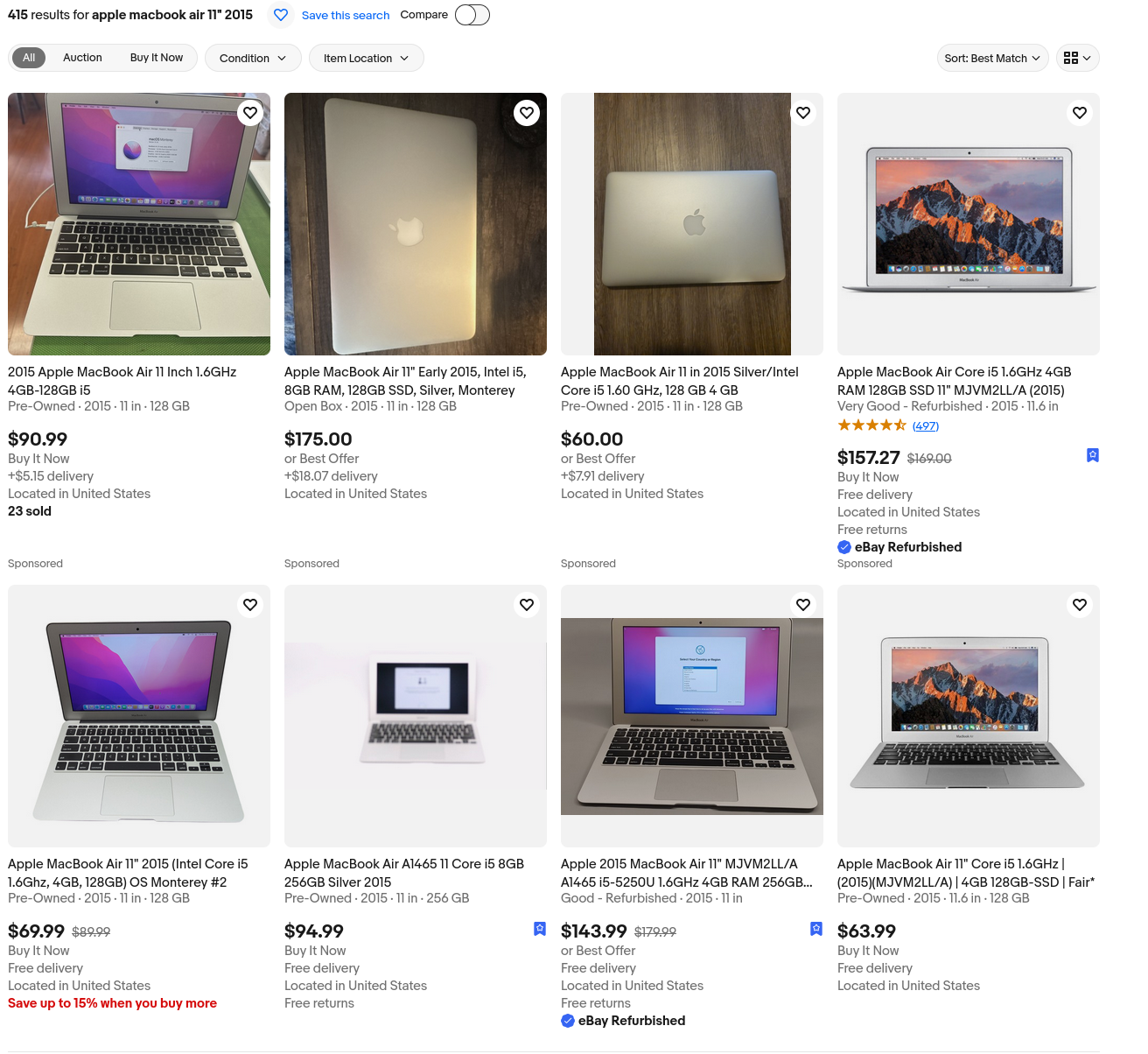

You can buy old MacBooks for dirt cheap. $100. $150. Sometimes less. Why? Because Apple, being Apple, stopped supporting them. Suddenly you’re stuck running an OS from 2017. A lot of useful software won't run; the internet declares the machine “obsolete.” That practice may make profits for Apple shareholders: consumers who perceive themselves as trapped in the Apple ecosystem – could one really give up instant AirPod pairing? – are induced to purchase the latest and greatest. But the casting of well built electronics into landfalls is very wasteful. Moreover, until about 2019 Apple even allowed mere mortals to upgrade RAM and storage and to install other operating systems on their machine without having to evade the ever watchful T2 security chip. These earlier machines are begging for Linux, which, particularly if you get a lighter distribution such as Arch (or NixOS or Guix) with Xfce or CachyOS, can run perfectly well on the sort of 4 GB RAM, 128 SSD machines that used to be the low end of offering from Apple, Dell, Lenovo and many other reputable vendors. Indeed, you can even run Hyprland under CachyOS, which gives you a very glitzy and very programmable tiling window manager (kind of like the one on Cosmic).

So after a few weeks of testing the waters with a Mac Pro 2013 trash can and figuring that if I could conquer getting its proprietary video system to work properly under Ubuntu I could do just about anything, I started buying computers. One after another. Because, until you realize that you can actually test various distributions on the same machine without too much difficulty, you might perceive a need for multiple testing platforms. Plus, they are so ridiculously cheap compared to their original prices or the prices of modern hardware. How could any Linux explorer not buy them? And so, before I knew it, I had bought seven computers for under $1,000 total, even including the cost of some memory upgrades that I plopped in after negotiating with Apple's proprietary and microscopic "pentalobe" screws. Indeed, I got two of those computers because I submitted ridiculously low "Best Offer" bids late at night for fun, wrongly figuring that the seller would never accept them. And, if I am being honest with my readers, I also succumbed to a well-specc'd Lenovo Thinkpad T480, as a high end machine on the theory that it could do "real work" and, because as a highly upgradeable device, was a great Linux investment.

I learned a lot from these purchases. I learned that, beautiful a piece of technology as it is, I might not have needed the Thinkpad. You can really do just fine doing real work in 2025 on one of these little machines. With CachyOS and and Xfce desktop environment, for example, you can run all the web-based large language models (Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, AI Studio). You can run Westlaw, LEXIS, midpage and your favorite legal research tools without a problem. You can run local AI tools such as AntiGravity and VS Code. Maybe you can't do all of this at once. And you do have to pay attention to the little "memory pressure" bar I put in the "Waybar" at the top of my window. But, as long as you are willing to take a little care and give up on 100% perfect compatibility with Microsoft Word, you can get your work done. For lawyers and law students alarmed at that last clause, please recognize that with the LibreOffice suite of products or the OnlyOffice suite, you can certainly work with most Microsoft Word files as well as Excel and (I am told) PowerPoint. And these products may have better security than commercial alternatives.

With all these machines around just waiting to be differentiated, I also succumbed to a typical Linux infection: ricing. Ricing is the art (and mild obsession) of customizing your desktop until it looks exactly how you want. Colors, fonts, animations, widgets—everything tuned just so. Is it productive? Debatable. Is it educational? I suppose so in the sense that you learn about the capabilities and aesthetics of computer desktop design in the way that Leonardo learned about the capabilities and aesthetics of various pigments.

Is thinking about keybinds at bedtime a sign that you’ve gone a bit too far? Possibly.

But ricing taught me minimalism in a very concrete way: you learn what matters because you configure everything yourself. Nothing is abstract. Nothing is free.

Privacy and Professional Hygiene

I also stumbled along the way into the larger world of privacy. Many Linux enthusiasts have a strong libertarian streak. Fear of big government. Fear of big corporations. A deep sense of wanting to control every aspect of your computing life and public footprint. Sometimes that concern veers into excess. But, perhaps more than ever, you don’t need to be paranoid to care about privacy. For lawyers—and for clients who think carefully about risk—privacy isn’t ideology. It’s professional hygiene. Reducing unnecessary data exhaust is just good practice.

This led me to explore browsers like: LibreWolf (principled, sometimes too strict), Brave (a pragmatic compromise), Min (beautifully minimal and more secure, perfect for my little 4 GB systems). All of these strip out information that might reveal information about you and protect you from much of the targeted advertising that form the business model of companies like Google. I didn’t become a zealot. I still use Chrome. I still use Gemini. I still use Microsoft products. I became more intentional. Linux made that possible by making tradeoffs visible.

The Big Twist: “Wait, I Can Program My OS?”

And then ... just when I thought I’d reached the bottom of the Linux rabbit hole, that remarkable YouTube algorithm confronted me with something that changed everything. There are Linux distributions that literally let you program your whole computer system! Not applications. Not programs running on your system. But key features of the system itself. And you can do so in a way that prevents the conflicts that beleaguer developers.

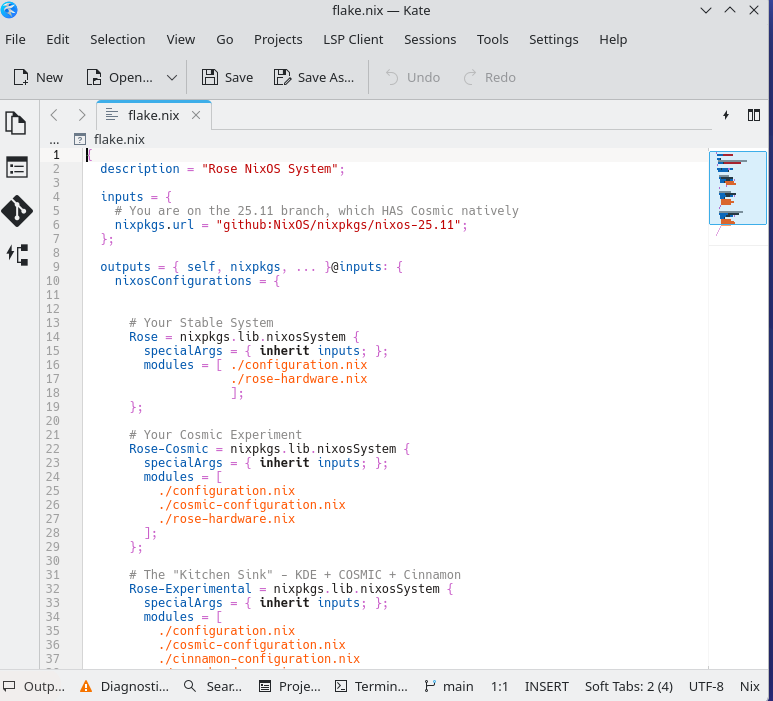

So this is where NixOS enters the story for real. NixOS doesn't rely on "statements"—those one-off commands like sudo apt install package that you shout at a terminal and hope for the best. Instead, it uses a functional language (Nix). To a lay reader, that might sound like a distinction without a difference, but it makes all the difference in the world. Traditional computer systems work is like giving a chef a list of random tasks ("Buy onions," "Chop carrots"). The step might individually make sense but collectively they create waste and conflict. NixOS gives the chef a master recipe.

In a traditional OS, you are just running a sequence of errands; if you forget one step or do it out of order, the whole meal can be ruined, and you might not know why. In NixOS, you describe the final result in a script. The system then evaluates that code and builds the environment to match your vision exactly. Moreover, it is not just any old code. It is code written in a functional language, Nix. Functional is a term of art; it does not mean "it works". It means the code is mathematically pure, avoiding the 'side effects' that clutter traditional systems. It is rooted in heavy duty ideas: formal logic and Lambda calculus—the idea that a given input should always produce the exact same output, every single time. As someone with 35 years of experience in functional programming—largely through the Wolfram Language—this clicked immediately. It moves system management from the realm of 'fingers crossed' to the realm of mathematical certainty. This is how I think. This is how systems should work.

So I have now built the system I want. It has a solid base. I can evolve it with sudo nixos-rebuild switch --flake . any time I want (And, yes, I am getting a tee-shirt made with that command emblazoned on it). I can roll it back to a working state whenever I break it. I can log into five different environments any time I want: Plasma, Cinnamon, Xfce, Hyprland, or Cosmic. NixOS comes with an enormous and very searchable repository of packages; it's not quite Arch Linux, but it is very strong. Moreover, I can reproduce my NixOS system on any machine I want. Big machines, tiny machines, PCs and Macs. I can port that configuration to your computer. Or a $150 laptop from eBay. And so, right now, I am writing this blog entry on a sub $100 EBay Apple Macbook Air 11" from 2015 with 4 GB of RAM running Cosmic without any problems, using Gemini, ChatGPT and other AIs to help me through the writing and research process. I have hooked up an old external monitor, which makes the experience even more pleasant. And if, in a few minutes, I decided I would enjoy my riced version of Hyprland and do the same thing, it would be a matter of logging out and logging back in. If that doesn't make you feel excited and empowered, you are just not a nerd.

Time for the Guix Digression

<digression>

There is, however, one thing I don’t love about NixOS. It uses Nix, a custom domain-specific language. To be sure, Nix is powerful enough and it is well-suited for its job of producing systems. But its very specialization means that it has lost the network externalities that come with many other languages. There's no huge community of people writing about it as there is with mainstream languages such as Python, JavaScript, C and others. It's not written about as much as other Linux distributions such as Ubuntu or Fedora or Debian. In the olden times before 2023 that obscurity might not have mattered quite so much. But now it does. It means that there is less data for AI to train on. It means that you have to be extra careful when asking AI for help about Nix. When data is sparse, AIs helpfully fill the gap with hallucinations. Although Gemini and Claude have come through pretty well for me notwithstanding the lack of training data, there's no question that hallucinations or just misguided responses have made it more challenging to set up camp in the land of NixOS.

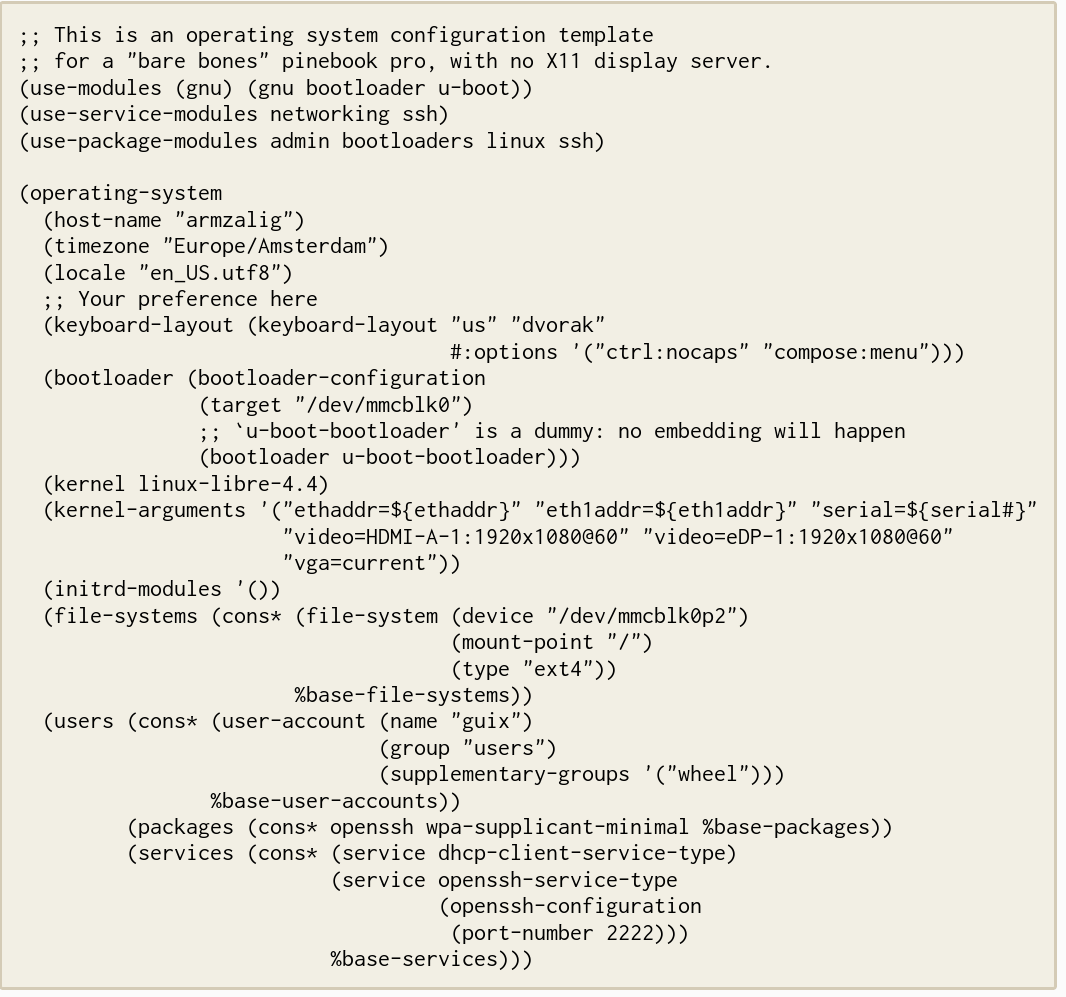

And it was this conceptual shortcoming of NixOS that took me on my most recent excursion Linux wonderland: Guix – properly pronounced as "Geeks." It too uses a functional language. But instead of using its own specialized language, Guix piggybacks on Scheme, which is an old and well-documented flavor of the Lisp, one of the ur-languages of computer science. Brilliant! Take NixOS's functional approach but instead of a custom language use one that has decades of documentation, a rich academic heritage, and—crucially—plenty of training data for AI assistants. When Claude or Gemini help you write Guix configuration, they're drawing on a deep well of Lisp/Scheme knowledge rather than improvising from sparse Nix examples. That matters enormously in 2025.

But Guix has embraced an uncompromising interpretation of Free Software Foundation principles, i.e. absolute user control over all code they run, and rejection any reliance on proprietary components—even when such reliance is functionally unavoidable in modern hardware and professional ecosystems. The FSF philosophy isn't wrong about everything. Proprietary software can create genuine problems—security vulnerabilities you can't audit, vendor lock-in, privacy violations. It does get annoying at times to "be the product" when you surrender your privacy for convenience. Fair points. But Guix orthodoxy on this point makes their system practically unusable for real work. Want to run it on Mac hardware? Good luck without proprietary WiFi drivers and firmware blobs. Need professional tools? Most legal tech, Adobe products, even basic things like Chrome require jumping through hoops with third-party repositories.

Here's the deeper irony: Guix is supposed to be empowering. Control your computing! Freedom from corporate overlords! And in some imaginary world where everyone runs free software and hardware magically works without proprietary drivers, maybe it would be.

But in the actual world—the one where you save old Macs from landfills, where colleagues send Word documents, law schools use Zoom, legal databases require specific browsers, and students need to collaborate using mainstream tools—Guix's purity becomes disempowering. You're not liberated from corporate control; you're disconnected from the ecosystem where work actually happens. The "freedom" to refuse proprietary software becomes the constraint that prevents you from participating in professional life. That's not empowerment. That's self-imposed isolation dressed up as principle.

Yes, there's Nonguix as a workaround. People associated with Guix have made some grudging compromises. But maintaining an unofficial channel to access forbidden software proves the policy is broken. Maybe there are other workarounds that some future YouTube video will tell me about. But in the interim, it looks as if you're fighting the system rather than using it.

The tragedy is that Guix could have been NixOS 2.0—same brilliant functional approach, but with a real programming language that AI can actually help you with. Instead, ideological purity relegated it to a tiny niche.

Meanwhile, I've discovered something practical: learning Scheme to understand Guix's approach actually helps with Nix programming. The functional thinking translates. AI assistants trained on Scheme – does anyone see a Claude Skill coming? – can reason about similar Nix patterns. So Guix became accidentally useful—not as my daily driver, but as a conceptual bridge to better NixOS configuration.

</digression>

A Final Realization About Cost and Access

Somewhere between EBay computer number six and seven and again while trying to come up with the legaled.ai angle for this rather personal blog entry, it hit me. I see students coming in with fancy computers and exiting law school with debt. But most students could get by extremely well on a sub-$200 computer if they’re willing to climb a very small Linux learning curve. And that curve is shallow if they stick to Mint or Cosmic. So pay for AI subscriptions. That's empowering. But think hard before incurring credit card debt or use scarce financial aid for glitzy computers.

What do students give up? Not much. LibreOffice handles most Word files. Web browsers work identically. The real sacrifice is conformity—and maybe that's the point.

Because here's the tension emerging Linux advocates face: Corporate law runs on Windows and Mac. Show up with your EBay Linux laptop and you're the person who needs "special accommodation" for standard tasks. That's a real cost, and I won't pretend otherwise. And law schools have hints of corporate culture that could likewise pose an issue. Many, for example, use ExamSoft as exam security software. It doesn't run on Linux. Neither does Exam4. So schools using that system will either have to accommodate Linux students with loaner laptops, switch to Proctorio, which does support at least some Linux distros (yay), or tell the student to borrow a friend's computer or (gasp!) hand write. I can't pretend students saving money and exploring computer science by getting Linux machines won't face issues.

But I also won't pretend that teaching requires preparing students only for the world as it exists. Law school should expand how you think, not just train you to click the right icons. Understanding Linux—really understanding how computers work—changes how you approach every technical problem afterward.

It's the same reason we teach legal theory even though partners seldom care about Ronald Dworkin. The knowledge reshapes your thinking.

So learn Linux if it interests you. Not as career preparation, but as intellectual development. For less than the price of an overpriced casebook (a story for another blog entry), you can build a system from scratch and actually understand what's happening when you press a key.

As for me? I'll keep tinkering with my small fleet of resurrected MacBooks. The journey turns out to be the destination. And that's enough.

Coda: The "Why" Question

After reading a draft of this post, a friend asked me a pointed question: Why? For 98% of people, a Mac or a Windows laptop from the 2020s is a marvel of engineering that just works. You open the lid, you write your brief, you close the lid. You attach devices and they are plug and play. Claude works just fine on a Mac. Does it work any better on Linux? (No.) Why should you or anyone else struggle with drivers, spend many hours learning how to program a system configuration in a niche functional language and retrain yourself in new forms of keyboard muscle memory just to achieve what Apple and Microsoft give you for free out of the box?

Do I have a better answer than the Mt. Everest "because it's there" response?

She has a point. In fact, she has the sensible point. For most professionals, the computer should be like a refrigerator; you don't need to understand the thermodynamics of the coolant to get successfully extract a can of H-E-B sparkling water from behind the Tupperware. But I think the better analogy is camping. We could live comfortably in climate-controlled houses, never braving a trail with bears or spending a night on the hard ground. Yet, some people still go into the woods. They do it because there is something vital about self-reliance, about understanding the fire you built yourself, and about seeing the stars without the glare of the city. Linux is "computing in the wild." It’s getting back to the "nature" of the machine. But if I have to justify the time spent along the way without metaphor, I think it comes down to three pillars: autonomy, economy with a make-weight capability support thrown in.

Autonomy and the End of the Tenant Model

When you use a modern commercial operating system, you are essentially a tenant. You live in a beautiful, high-rent district designed by Apple or Microsoft. They choose the colors, they decide when the locks get changed, and they can move your furniture around whenever they please via a mandatory update. If you don't like the new layout, your only real option is to move out, which is a massive pain.

Linux, and specifically the reproducible model of NixOS, changes you from a tenant to an owner. I don't just use the systems I am now using; I define them. If I want a workspace that is entirely keyboard-driven and looks like a 1980s terminal, I can have it. If I want a sleek, modern interface that mimics the best of macOS but without the telemetry back to Mountain View, Redmond or Cupertino (or Beijing for that matter) , I can have that too. That autonomy—the ability to turn the computer back into a personal tool rather than a corporate portal—is deeply satisfying.

Economy as Environmental and Financial Sanity

There is also the matter of economy. We have been trained to believe that a five-year-old computer is a paperweight. My fleet of sub-$200 eBay finds proves that is a lie. By stripping away the bloat of modern commercial operating systems, these machines run faster than they did the day they were manufactured.

As someone who watches students take on five or six figures of debt, and who sees poor people in our community unable to access AI (or even the web) to help meet legal needs, the idea that we can resurrect high-quality hardware for the price of name-brand sneakers feels like a healthy counter-narrative. Struggling public interest organizations or even small town government can take advantage of the opportunities too. Not that I'm much of an environmentalist, but I do find a bit of pleasure in selective resistance to our disposable culture.

The Capability Make-Weight Argument

Finally, although it did not motivate me to embark on the journey, and I can't say it's my best argument, if I must defend this journey as directly relevant to my work at my law school or for legaled.ai, I can throw in a simple truth: Linux is the native habitat of Artificial Intelligence. While Windows and Mac are wonderful for consuming AI through a browser, Linux is where AI is actually built, trained, and optimized. By working in a "bare metal" Linux environment, I learn more about the world developers inhabit. And if I or my students ever do access fancy hardware, the learning gained on small systems will serve me well when I gain access to performance efficiencies that commercial systems purposely lock away. Familiarity with NixOS will help us solve the notorious "dependency hell" of data science. We can create isolated, mathematically reproducible environments ensuring that an experiment running today will work exactly the same way next year. That's a very nice fringe benefit of the journey.