What the heck did the Supreme Court just do?

Using AI to try to make sense of NIH v. APHA

This afternoon, the Supreme Court released one its most inscrutable opinions – or, rather, five of its most inscrutable opinions. The catalyst was an emergency appeal in a case called National Institutes of Health v. American Public Health Association, which questions whether the NIH could lawfully terminate thousands of previously awarded research grants—especially those involving DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion), gender identity, and COVID-19—after new executive orders redirected funding priorities. I defy anyone (except possibly Professor Steve Vladeck) to swear they understood this set of opinions on first reading.

The result of my confusion was a conversation this evening was ChatGPT in which we collaborated on an effort to get to the bottom of the matter. The result is a 3,500 word article that attempts to stradle a legal professional/journalist audience and explain what the case is really about. Hint: it's a continuation of the remedies and forum shopping battle that underlay last term's decision in Trump v. CASA, which was the basis for one of this blog's first entries and whose virtual museum this blog inspired and described.

For those who doubt what human-AI collaboration can accomplish, I present the article here. It doubtless has warts; but I immodestly believe it is likely to be the best thing yet published on the decision. It should go viral. Yes, I have edited it. But very, very lightly. I ate my own dog food and used the method described in my blog post of earlier today to get it to draft in my style without much intervention.

I've also used NotebookLM AI to create an audio and video summary of this blog entry.

The Strange Triumph of the Lonely Concurrence: Remedies, Jurisdiction, and Politics in NIH v. APHA

NIH v. APHA is not merely a skirmish over public-health grants; it is the newest chapter in the Supreme Court’s multi-year effort to redraw the law of federal remedies and forum selection. To understand why a single Justice’s idiosyncratic “split-forum” view now governs—despite eight colleagues rejecting it—you have to connect three strands: the Bowen baseline for APA remedies, Trump v. CASA’s retrenchment on nationwide injunctions (with its studied hesitation about vacatur), and the Court’s recent channeling of money-adjacent disputes into the Court of Federal Claims. Along the way, the political context matters: these fights are unfolding amid rapid reversals of federal policy on DEI, gender identity, and COVID-related research in the Trump Administration’s second term.

I. What Just Happened in NIH v. APHA—and Why It Matters

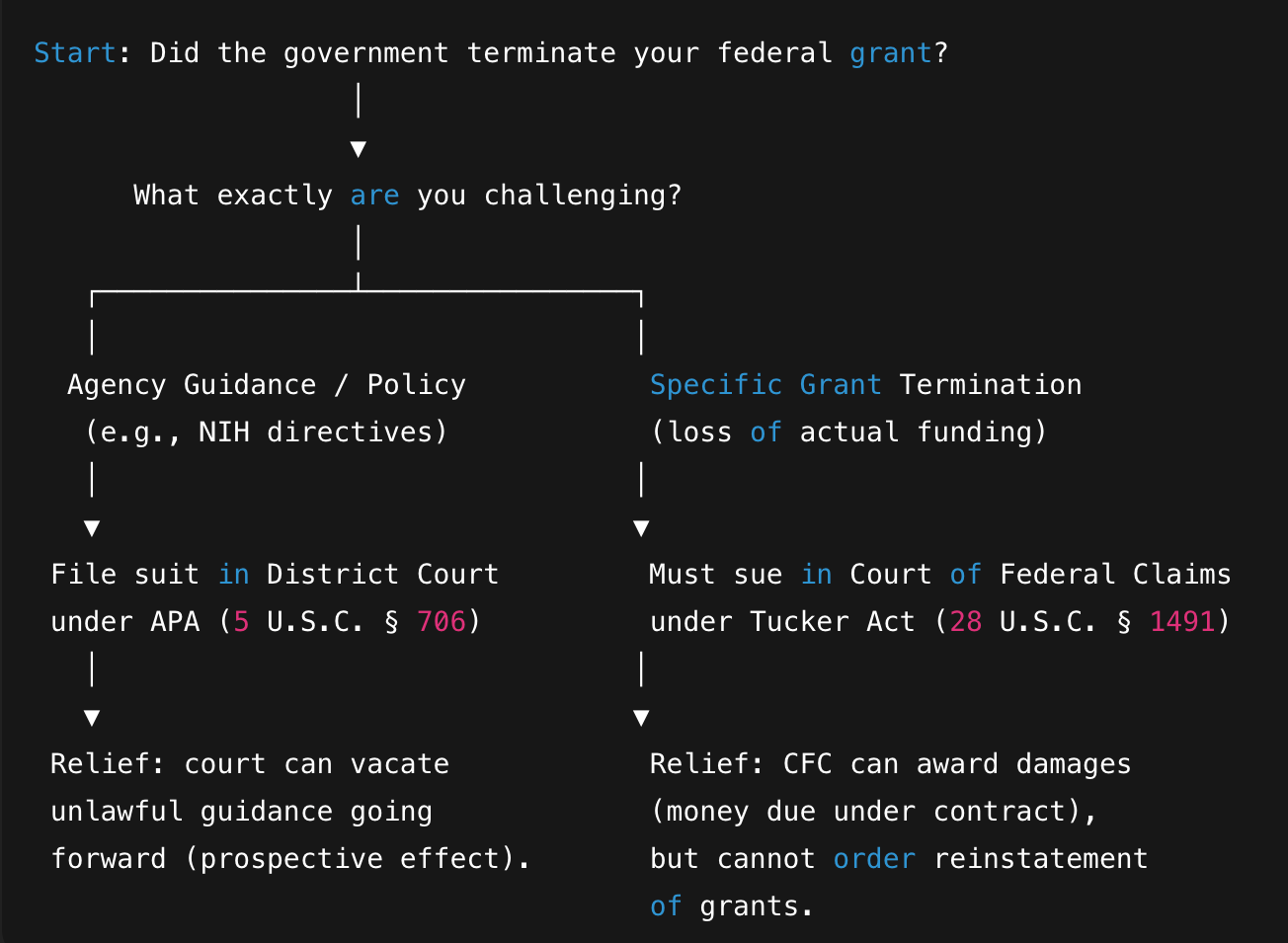

In late winter 2025, the National Institutes of Health moved quickly to “align its funding with changed policy priorities” announced in a trio of executive orders. Internal guidance followed: NIH would no longer fund research “related to DEI objectives, gender identity, or COVID–19,” and it would discontinue practices that awarded grants based on race. NIH then terminated a large number of ongoing grants. Researchers, professional associations, and states sued in the District of Massachusetts, challenging both the guidance and the terminations under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The district court vacated the guidance and the “resulting” terminations and ordered disbursement “forthwith.” The First Circuit declined to stay that judgment. The government sought emergency relief in the Supreme Court.

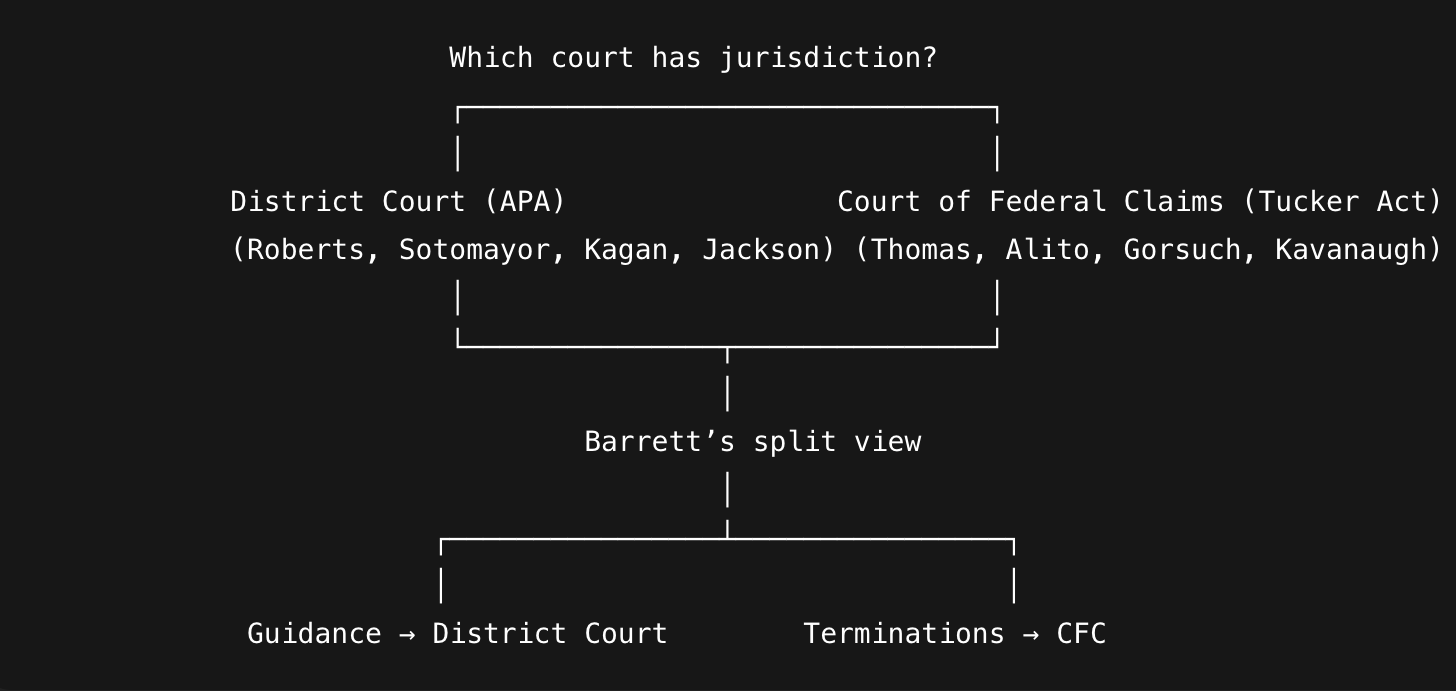

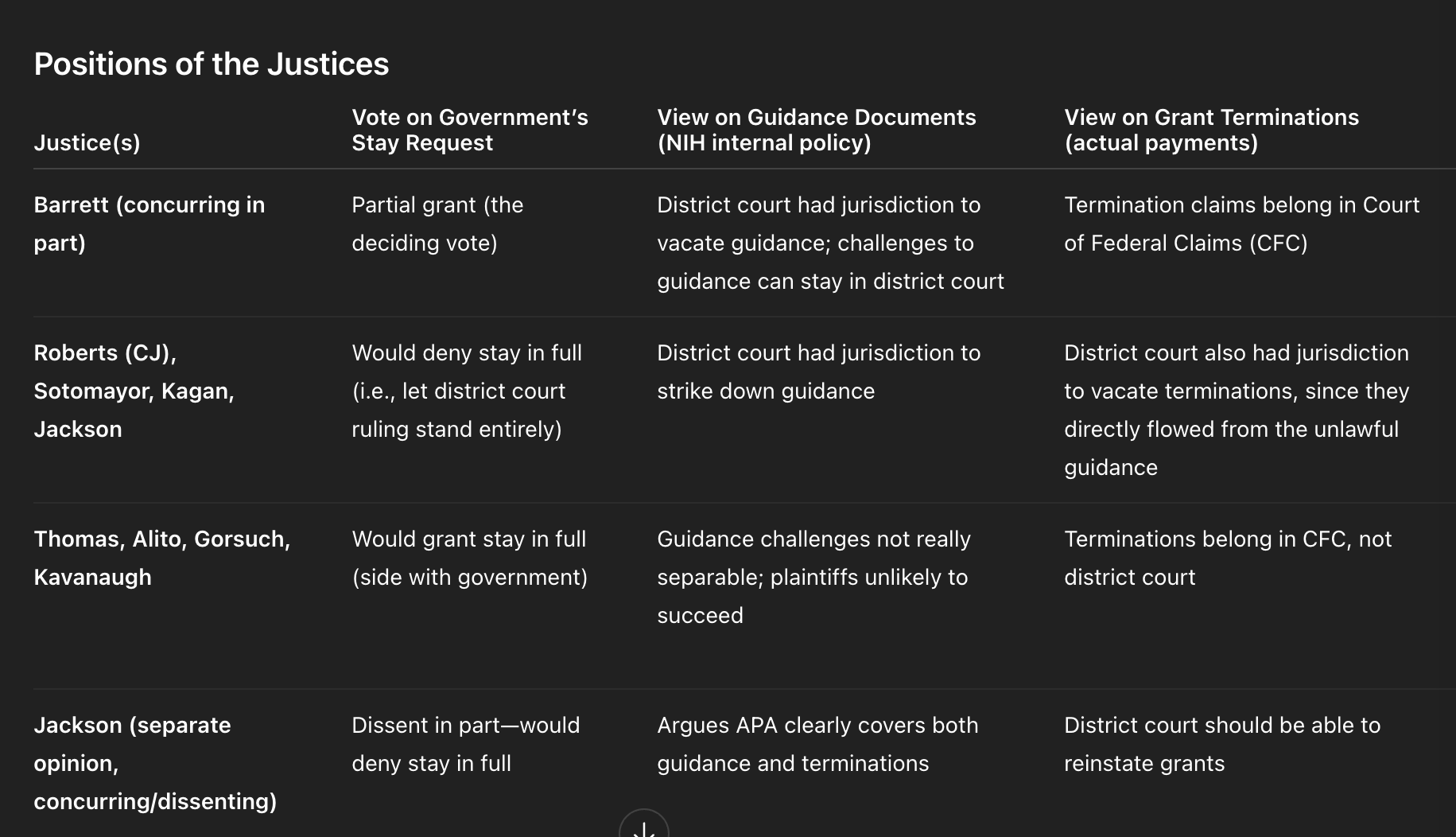

On August 21, 2025, the Court granted a stay “in part.” It stayed the district court’s judgments as to the grant terminations, but not as to the vacatur of the guidance. In short: the policy is off the books for now, but terminated grants do not spring back to life by virtue of that vacatur. Four Justices (Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh) would have granted a full stay; four (Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan, Jackson) would have denied it entirely. Justice Barrett alone supplied the fifth vote for a middle course.

The upshot is a jurisdictional and remedial split that almost no one affirmatively endorsed: challenges to guidance can proceed in district court; claims seeking to restore terminated grants must go to the Court of Federal Claims (CFC) under the Tucker Act. The Court anchored the latter proposition in its per curiam order earlier this year, Department of Education v. California (2025)(per curiam), which had treated suits functionally seeking payment under grants as contract-type claims “founded upon” agreement with the United States, and therefore exclusive to the CFC. In NIH v. APHA, the Court emphasized that the APA’s “limited waiver of [sovereign] immunity” does not authorize district courts to order relief “designed to enforce any ‘obligation to pay money’ ” under those grants.

Two more features of the order are notable. First, the Court accepted the government’s irreparable-harm theory on the terminated-grants piece: while “loss of money” is usually not irreparable, it becomes so if the funds “cannot be recouped” once spent; here, plaintiffs had not committed to repay if the government ultimately prevailed. (The order invokes Justice Scalia’s in-chambers reasoning in Philip Morris USA Inc. v. Scott, 561 U.S. 1301 (2010) (Scalia, J., in chambers).) Second, the Justices openly disagreed about how California applies, about whether the guidance/termination split makes doctrinal sense, and about what forum (district court or CFC) can actually provide effective relief. The opinions—Barrett’s controlling concurrence in part; Roberts’s concurrence/dissent joined by three; Gorsuch’s concurrence/dissent joined by Kavanaugh; Kavanaugh’s separate writing; and Jackson’s partial concurrence/dissent—expose a Court divided not just about outcomes but about the architecture of judicial review.

II. The Political Context the Law Can’t Ignore

The policy pivot underlying this case is not routine. NIH acted “in recent months” to implement a suite of early-term presidential directives on DEI, gender identity, and COVID-related research priorities; plaintiffs say the agency raced to cancel thousands of grants with little regard for statutory constraints or scientific need. The district court found the process “breathtakingly arbitrary and capricious,” with indicia (on that court’s factual record) of discrimination in what was cut. The Administration, for its part, cast the actions as necessary to align funding with new national priorities. This is hardball public law in real time, and it fits a visible pattern in the current political moment: rapid reversal of prior-term programmatic commitments coupled with litigation over the speed, method, and lawfulness of administrative implementation. Recognizing the political context of the case is not “taking sides.” It is acknowledging an explanatory fact about why these cases arrive on the emergency docket and why they fracture the Court.

III. Bowen v. Massachusetts and the APA’s Remedy Blueprint

To make sense of the split that NIH v. APHA produces, start with Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U.S. 879 (1988). There, Massachusetts challenged the federal government’s disallowance of Medicaid reimbursements. The government argued the state’s lawsuit belonged in the Claims Court (now CFC) because it sought money. The Supreme Court disagreed. It distinguished between (i) substitutionary money damages (compensation for a past wrong, the core of Tucker Act jurisdiction) and (ii) specific relief under the APA that prospectively sets aside unlawful agency action—relief that may result in the release of funds but is not itself a damages award. On that logic, district courts may order APA relief (vacatur or injunction), and the incidental fiscal consequences do not transmogrify those suits into Tucker Act cases.

Bowen did not merely resolve a forum squabble. It supplied a mechanism that state and institutional plaintiffs used for decades to challenge federal benefit and grant decisions in district courts nationwide, with access to preliminary relief and appellate review in the regional circuits. The core intuition was simple and administrable: if you are challenging agency action as unlawful, the APA is your vehicle and district court is your forum—even if Treasury dollars flow as a result. If you are suing on a contract, you go to the CFC.

In doctrinal shorthand, Bowen said: APA “set-aside” relief is equitable and prospective even when money is the practical consequence; that does not turn the claim into a Tucker Act suit.

IV. The Rise of Universal Injunctions and Trump v. CASA

By the 2010s, district courts—especially in high-salience fights over immigration, health policy, and environmental regulation—were issuing nationwide or “universal” injunctions that barred federal policies’ enforcement against anyone, not just the named plaintiffs. Critics called this “one-judge veto” a misuse of equity that fueled forum shopping and policy whiplash. The Court eventually intervened.

In Trump v. CASA, Inc. 606 U.S. ___ (2025), the Court—through an opinion by Justice Barrett—sharply limited universal injunctions. The majority insisted that traditional equitable principles authorize courts to grant plaintiff-specific relief, not nationwide decrees that extend to nonparties. Crucially, however, the opinion reserved an increasingly important question: whether vacatur under APA § 706(2)—which says courts “shall… set aside” unlawful agency action—functions as “party-specific” or “rule-wide” relief. In footnote 10, Justice Barrett left that question open.

That reservation mattered immediately. If universal injunctions were out, sophisticated plaintiffs would naturally reach for vacatur as the next-best tool to halt an unlawful policy as such. On its face, vacatur speaks in the register of object-focused adjudication: the unlawful agency action is “set aside.” On one view, that means the rule or guidance cannot be applied to anyone, not just to the parties before the court. On the opposing view, vacatur is simply the APA’s label for the remedial consequence of a merits judgment, but the decree must still track equitable limits (i.e., party-specific enforcement). CASA did not settle that debate. It guaranteed, instead, that vacatur would become the battleground.

V. Department of Education v. California and the CFC Turn

Earlier in 2025, the Court decided Department of Education v. California,604 U.S. ___ (2025) (per curiam), in an emergency posture, staying a district court order in a grants case and signaling that claims “based on” the government’s obligation to pay money under grant agreements belong in the CFC. The per curiam reasoned that the APA’s waiver of sovereign immunity does not extend to judicial orders that, in substance, enforce contractual “obligation[s] to pay money.” That interim order—controversial for its speed and brevity—nonetheless changed the conversation. It warned lower courts against reframing contract-adjacent disputes as APA claims and suggested that, when the practical relief is Treasury payment under an agreement, the Tucker Act controls.

Whether California undercuts Bowen depends on how you draw the line: Is the plaintiff challenging an agency’s lawfulness (APA), or enforcing a promise to pay (Tucker Act)? What California did, as a practical matter, was shift courts’ presumption toward the latter whenever terminated grant payments are at stake.

VI. NIH v. APHA: Opinions, Votes, and the “Split-Forum” Result

The NIH v. APHA opinions crystallize the stakes.

Justice Barrett (controlling concurrence in part) endorsed a two-track scheme. Challenges to internal guidance—documents that set policy but do not themselves disburse money—can proceed in district court under the APA. Challenges to grant terminations—decisions that cut off payments under existing awards—must proceed in the CFC. Vacating guidance does not “reinstate” terminated grants; the district court had to issue a separate order to that effect, which in Barrett’s view exceeded its jurisdiction. Plaintiffs, she noted, can litigate sequentially: pursue APA claims against the guidance in district court; then, if they seek compensation for termination, sue in the CFC. This bifurcation, she added, reflects the “jurisdictional scheme governing actions against the United States,” which often requires multiple actions to obtain complete relief.

Chief Justice Roberts (joined by Sotomayor, Kagan, Jackson) would have denied the stay outright, keeping both the guidance and the terminations within district-court APA review. On his reading, the district court’s vacatur of the directives was “prospective and generally applicable,” well within Bowen’s ambit, and the terminations “result[ed]” from those directives. Given the government’s own characterization of a “uniform policy” implemented “globally,” he saw no need to “split [the case] into two parts.”

Justice Gorsuch (joined by Kavanaugh) would have granted a full stay. For him, California’s ratio decidendi binds lower courts: grant-termination suits are Tucker Act suits, and attempts to relabel them as APA actions cannot evade the jurisdictional bar. He criticized the district court for relying on dissenting views in California while disregarding the Court’s controlling guidance. He also would have stayed the guidance vacatur on standing and separability grounds.

Justice Kavanaugh concurred separately to stress two points: (1) grant-termination claims belong in the CFC; (2) the guidance challenge is weak on its own terms (e.g., agencies need not define every term in internal documents guiding discretionary resource allocation), and the equities tilt toward the government absent a commitment that plaintiffs would return funds if they ultimately lose.

Justice Jackson (concurring in part and dissenting in part) would have denied the stay fully. She sees California as a rushed and under-reasoned emergency order that lower courts and the Supreme Court are now over-reading. She contends that the majority’s split erects a remedial “labyrinth”: district courts can declare policies unlawful, but no court can restore funding promptly; the CFC’s remedial powers are limited, and § 1500 and preclusion rules make sequential litigation fraught. As she puts it, the Court’s approach gives plaintiffs “the mirage of judicial review while eliminating its purpose.” She also flags looming “final agency action” pitfalls if guidance challenges are severed from terminations.

Two institutional stakes surface in these writings. First, remedies: Is vacatur a meaningful tool after CASA if it cannot restore the status quo ante when money has been cut off? Second, forum: Who decides and how quickly? District courts (with preliminary relief and circuit review), or the CFC (with damages years later and no injunction)?

VII. Vacatur After CASA: A Back Door or a Hollow Door?

If universal injunctions are disfavored (as CASA holds), can vacatur under § 706(2) still provide system-wide relief? NIH v. APHA’s practical answer is: sometimes, but not when the relief would functionally reinstate payments or compel disbursements—at least not in district court.

The district court here vacated both the guidance and the “resulting” terminations, apparently reasoning that if the predicate policy is unlawful, so are the actions taken under it. Justice Barrett’s controlling view cuts that causal chain in half: vacatur of guidance is permissible (subject to other defenses), but the “resulting terminations” do not automatically fall within district-court remedial power. They must be litigated in the CFC. The government, and Justices aligned with it, view that severance as necessary to prevent vacatur from becoming an “end-run” around CASA’s limit on universal injunctions. The Roberts bloc sees the severance as incoherent and Bowen-inconsistent: if the directive is unlawful, forbidding its application to plaintiffs necessarily entails setting aside the termination decisions it generated, with the incidental consequence that money flows.

This is where the rubber meets the road. As a litigation strategy, plaintiffs will still seek vacatur of policies to stop prospective enforcement “as to everyone.” But NIH v. APHA signals that vacatur alone may not deliver the relief plaintiffs most need in grant-termination cases: restoration of ongoing funding. Even if a policy falls, plaintiffs may need a second trip to the CFC—without equitable remedies and without the leverage of a preliminary injunction—to recover compensation, after the lab or clinic has shuttered.

VIII. Preclusion, § 1500, and the “Labyrinth” Problem

Could plaintiffs leverage a district court’s vacatur to win summary judgment in the CFC? Theoretically, they would invoke issue preclusion: the legality of the guidance was actually litigated and necessarily decided; the government should not relitigate that issue. But two obstacles loom.

First, the Supreme Court’s forum split frames the guidance challenge and the termination dispute as legally distinct—one an APA question, the other a Tucker Act question. That framing gives the CFC space to say: whatever the district court thought about “guidance,” the CFC’s task is to decide whether NIH lawfully terminated particular awards under the relevant grant terms (or money-mandating statutes). Collateral estoppel is therefore uncertain.

Second, 28 U.S.C. § 1500 bars the CFC from hearing claims that share “substantially the same operative facts” as claims pending in another court. Plaintiffs may therefore be forced to proceed sequentially, not in parallel. By the time the district-court APA case ends, the record may have shifted; any preclusion arguments get messier; and the practical harm (lost research capacity) is already baked in. Justice Barrett acknowledges the two-track, sequential reality and treats it as a feature of Congress’s sovereign-immunity scheme. Justice Jackson sees it as a bug that deprives plaintiffs of “complete relief.”

IX. Is This Just About Law, or Also About Politics?

It is both. Formally, NIH v. APHA is about the scope of the APA’s waiver, the meaning of “set aside,” and the Tucker Act’s channeling of claims “founded upon” contract. Functionally, it is about who gets to stop a rapid policy reversal and how fast they can do it.

On one side is the institutional preference to funnel money-adjacent disputes into a specialized court with limited equitable powers and a slower remedial tempo. That preference dampens the ability of states, universities, and NGOs—often suing in circuits perceived as more receptive to their claims—to secure nationwide halts to federal policies. On the other side is the Bowen-inflected view that the APA is meant to police agency reason-giving and legality in real time, and that district courts are the correct forum for that oversight even when money is at stake. The present Administration’s early-term directives on DEI, gender identity, and COVID-related research funding make the context salient: plaintiffs contend that NIH’s mass terminations were arbitrary, inadequately reasoned, and sometimes discriminatory; the Administration argues that reprioritization was both authorized and urgent. No one can credibly assess the Court’s remedial moves without acknowledging that policy stakes are driving the forum war.

X. How the Votes Produced a Rule Almost No One Wants

The structure of emergency relief made this outcome possible. Four Justices wanted all district court; four wanted all CFC. Justice Barrett alone wanted split jurisdiction. In stay practice, the Court had to pick a disposition. Barrett’s position generated five votes for granting a stay as to terminations (her vote plus the four conservatives) and five for denying a stay as to guidance (her vote plus the four liberals). That is how an approach rejected by eight Justices as a matter of first-best preferences becomes controlling law. The result may be a bizarre statutory scheme that it is hard to imagine Congress thought through. [That last sentence can be blamed on me.]

The opinions underscore the oddity. Roberts says the government itself painted the picture of a “uniform policy” implemented “globally,” making it a paradigmatic APA case in which relief for plaintiffs logically dissolves the “resulting” terminations. Gorsuch says like cases must be treated alike, California controls, and district courts cannot wish it away with dissenting views. Jackson says the Court has constructed an obstacle course “nowhere in the relevant statutes” that effectively insulates abrupt policy shifts from timely judicial correction. Barrett, for her part, stresses that two-track litigation and sequential suits are a built-in consequence of Congress’s partial waivers of sovereign immunity.

Is this stable? Maybe not. On full merits, the guidance challenge may draw sharper “final agency action” arguments; some Justices may be moved by the remedial-gap problem; the Court could align five votes behind one forum. But for now, the “lonely concurrence” is the law of the land.

XI. Where Bowen Now Stands

Bowen is not overruled. Its core distinction between substitutionary damages and specific APA relief survives, in principle. But its operational space has narrowed.

Three developments mark the retrenchment. First, CASA curtails universal injunctions, making vacatur the focal remedial tool—yet the Court is plainly wary of vacatur functioning as a universal injunction by another name. Second, California tilts grant-termination disputes toward the CFC when payment obligations are at stake. Third, NIH v. APHA severs the line between unlawful policy and its concrete fiscal effects, holding that even when plaintiffs establish the former in district court, they must seek redress for the latter elsewhere.

In combination, those moves hobble the practical bite of APA remedies in high-stakes, time-sensitive grant disputes. Plaintiffs can still set aside the rule. They just cannot necessarily get their funding back in the same courtroom, or in time to save the program the funding supported.

XII. A Note on Irreparable Harm and the Emergency Docket

The order’s irreparable-harm analysis is brief but consequential. The Court leaned on Philip Morris v. Scott to say that “loss of money” can amount to irreparable harm if the funds are “irrevocably expended” and “cannot be recouped.” Because plaintiffs did not commit to repay if they lost, the government faced irreparable injury from ongoing disbursements during appeal. That framing will recur in future stay applications: agencies will argue that compelled interim payments are non-recoverable and thus irreparable; plaintiffs will be pressed to choose between promising to repay (thereby undermining their ability to litigate or sustain operations) or risking a stay. This is a subtle but real shift in the equities on the shadow docket.

XIII. Practical Guidance for Litigators and Observers

Two practical consequences follow from NIH v. APHA.

First, expect paired suits—an APA action in district court aimed at vacating policy, followed (sequentially, to avoid § 1500) by a Tucker Act action in the CFC seeking compensation for terminations. Counsel will have to plan record-building and timing with preclusion in mind, knowing that the Supreme Court’s framing invites the CFC to treat APA vacatur as non-determinative on contract-law issues.

Second, do not assume vacatur will accomplish everything a universal injunction once did. It can still remove a policy from the legal landscape prospectively. But when payments have been cut off, vacatur may be only half a remedy. Plaintiffs will need contingency planning—bridge funding, alternate sponsors, or state appropriations—to keep programs alive while a damages suit winds its way through the CFC and Federal Circuit.

XIV. Conclusion: Remedies, Forums, and the Politics We Cannot Unsee

NIH v. APHA is a case about administrative law, but it is also a case about power: the power to pick the forum, to choose the speed of adjudication, and to define what counts as meaningful relief. It arrives in a charged political moment—early-term presidential reversals of prior research policies in areas (DEI, gender identity, COVID-related projects) that are culturally salient and intensely contested. The Supreme Court’s fractured order, with Justice Barrett’s solitary “split-forum” view controlling, advances a remedial and jurisdictional project that has been gathering steam: constraining nationwide relief, channeling money-adjacent disputes into the CFC, and narrowing the practical reach of Bowen.

Whether one regards that project as overdue discipline or as an erosion of the APA’s central promise, the stakes are unmistakable. For law professors, this is a teachable synthesis of doctrine, institution, and politics. For journalists, it is a through-line that explains why a “stay in part” on a Thursday afternoon can quietly reset how and where the next big policy fight will be won—or lost.

Learn More

I've created a NotebookLM notebook containing a briefing, study guide and audio and video summaries of the case and this blog entry. Here is the link.

Appendix

Another virtue of AI is that it can swiftly produce tables and graphics. Here are a couple generated during this evening's conversation.

| Feature | Federal District Court (APA) | Court of Federal Claims (Tucker Act) |

|---|---|---|

| Core jurisdiction | Challenges to agency action under the APA (arbitrary, capricious, contrary to law, ultra vires) | Contract and money-mandating claims against the U.S. |

| Relief available | • Vacatur of unlawful rules/guidance | |

| • Injunctions (prospective, can stop agency from enforcing policy) | ||

| • Declaratory judgments | ||

| • Practical effect: can reinstate grants by voiding the policy that terminated them | • Money damages (past due payments under a grant viewed as a contract) | |

| • Occasionally equitable relief incidental to money judgment, but no broad injunctive power | ||

| • Practical effect: cannot reinstate ongoing funding; can only write a damages check after years of litigation | ||

| Speed / leverage | Injunctive relief can be immediate, forcing the agency to restore funding midstream | Recovery comes later; by then, research programs may have collapsed |

| Systemic impact | One district-court judgment can block an agency’s policy nationwide (especially if affirmed on appeal) | Relief limited to the plaintiff’s claim; no ability to vacate policy for everyone |

| Forum politics | Wide range of venues, some in circuits with judges more skeptical of Trump Administration policy shifts (e.g. 1st, 2nd, 9th Circuits) | Single specialized court in Washington, D.C.; narrower remedies, less political diversity, 15-year appointed judges |