The Killer App can now write law review articles: Learning Resources v. Trump

Imagine a world in which legal scholarship is not the result of months of research and writing and in which the field of all possible articles is no longer sparsely populated because of that constraint. Instead, imagine a world in which the space of all possible law review articles can be rapidly filled by AI. No, we are definitely not there yet. And we may not be there for some years if ever. The space is enormous, humans still have a role to play, and, even with AI assistance, production of quality legal scholarship definitely still takes time. Moreover, quality scholarship probably still requires a modicum of human insight with which it will be challenging to bestow AI. But as of early 2026, I contend that AI grounded in the legal raw materialscan write pretty good law review articles with minimal human intervention. This blog entry is my attempt at proof.

I want to tell you all that it took at produce a 15,000-word article on Learning Resources v. Trump, the tariffs case decided yesterday by the Supreme Court. The entire process took about two hours, during most of which I could clean the kitchen as Claude Cowork toiled in the scholarly fields. It relied heavily on what I described in a prior blog entry as The Killer App, combining agentic AI (Claude Cowork) with a great model (Opus 4.6) with a connector (Midpage AI MCP) with a legal database (Midpage AI). If you want to see the results and defer examining the process, just go to the bottom of this entry and read the article. Alternatively, go to this link to read the result as a Microsoft Word (docx) file. But here first is a screenshot of what Claude could produce and then a description of what it took to let AI produce what sure looks like a bona fide law review article.

I started by feeding Claude the 170-page PDF opinion fresh off supremecourt.gov.

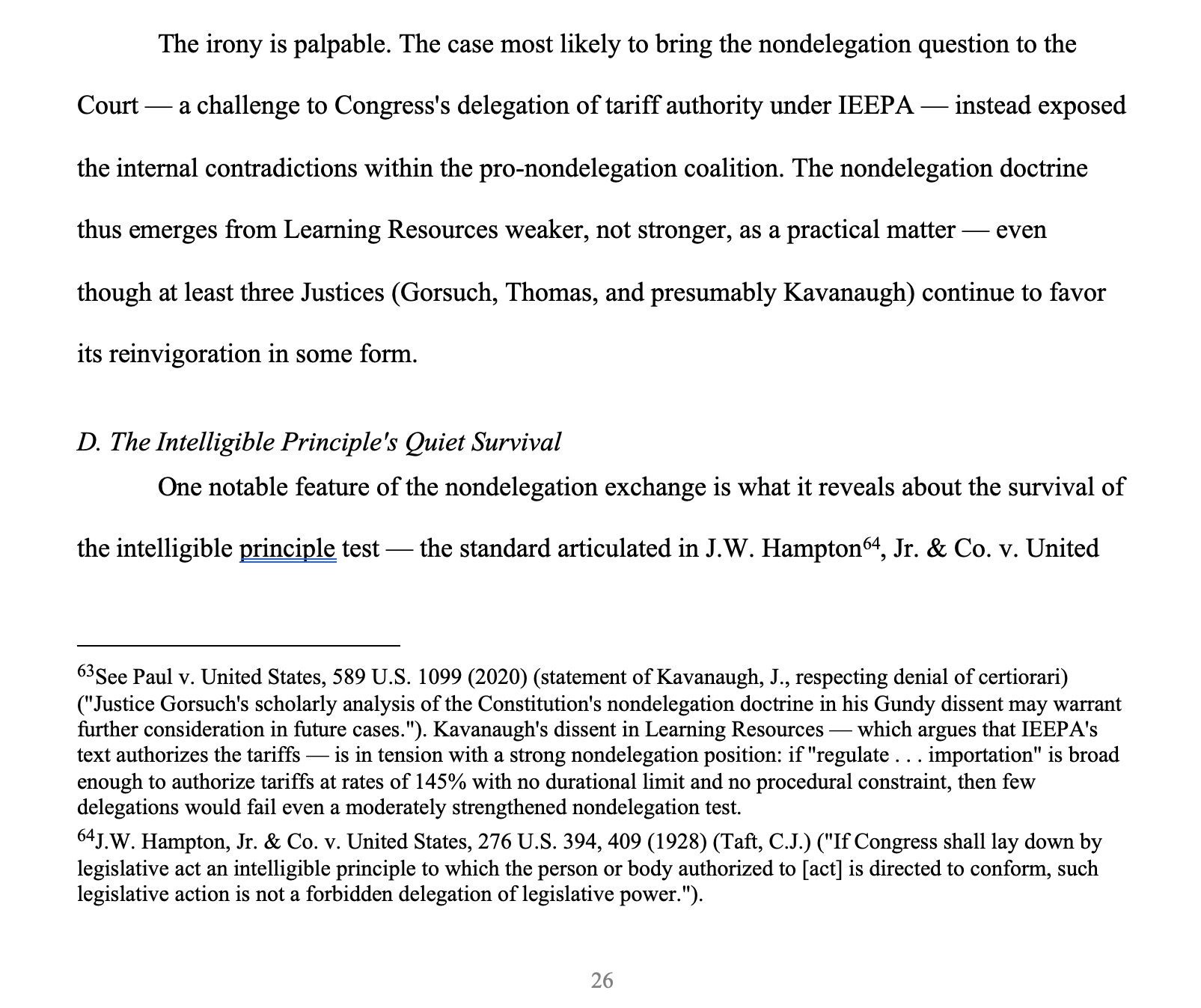

Claude produced this output. I have posted all the artifacts produced in yesterday's work on this Github repository.

I then asked Claude to produce a "modernized" version of the opinion in what I call "Tufte-Latex" form using a pre-baked skill. My idea was that I could give this excerpted version of the case to my class this week, which, as it happens, was studying the major questions doctrine and the non-delegation doctrine, both of which form important parts of Learning Resources v. Trump.x`

Here is the first page of the result. You can see that it is a kind of reconstruction of the opinion with sidenotes in the style of Professor Edward Tufte (one of my heroes).

Since Claude was kind of busy and I had been contacted by the Houston Public media outlet for my views on the case, I then fed another AI (Gemini) a request to read the opinion and focus on its practical implications, with attention to "the local angle." Houston imports a lot of tariffed goods. I then fed Gemini's output back into Claude and asked it to review and revise the work. It then responded with the following comments and a Word document.

I then asked Claude for something punchy to provide interviewers. It came back with 10 pull quotes. Here's an excerpt of what it produced:

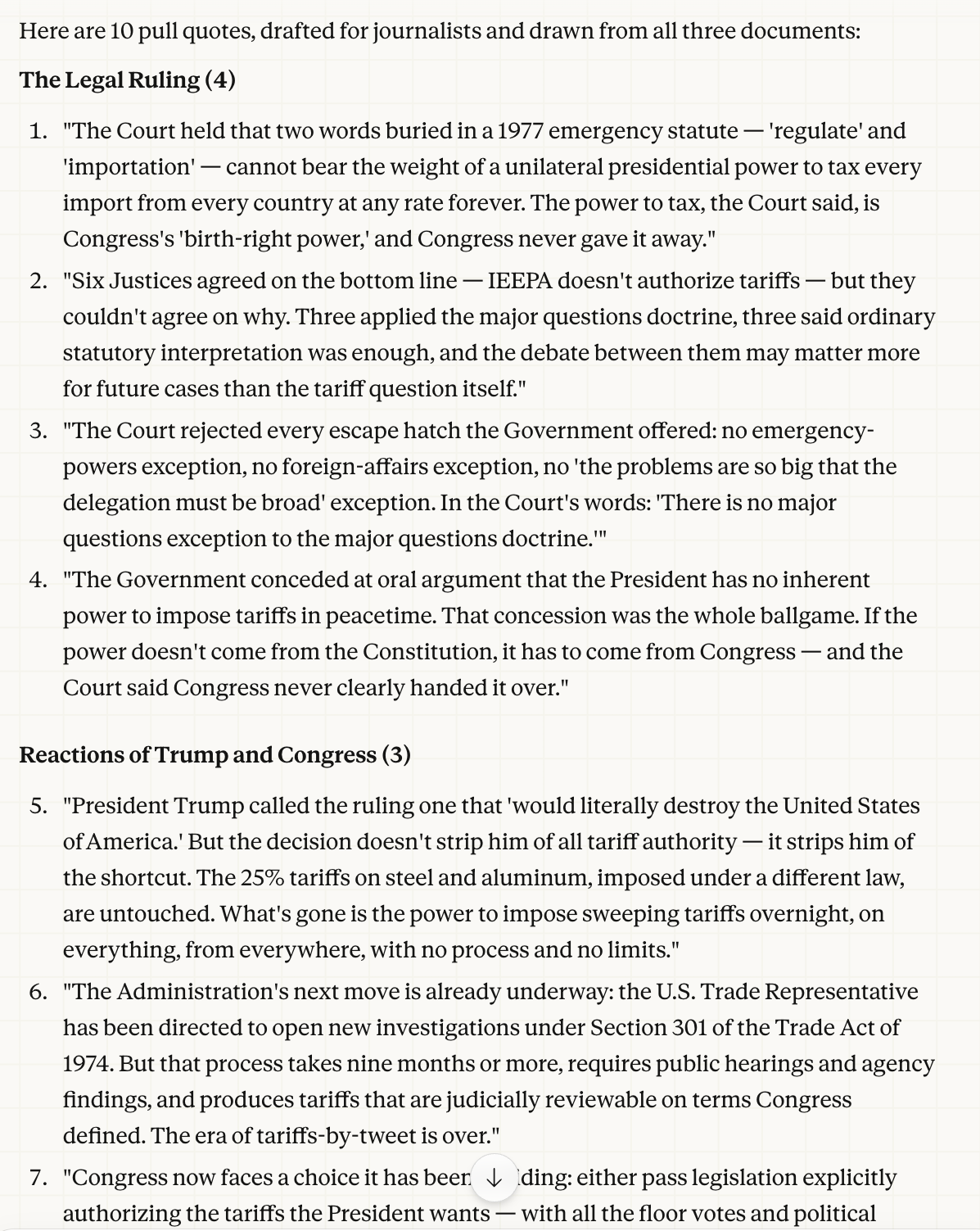

By this time I was thinking it might be possible to generate a class lecture or maybe even an instant law review article about the case, a form of just-in-time legal scholarship. And, here I relied on some human expertise and teaching expertise. My class has already studied some of the cases cited in Learning Resources and so I wanted to see how the court had dealt with those precedents. Thus ...

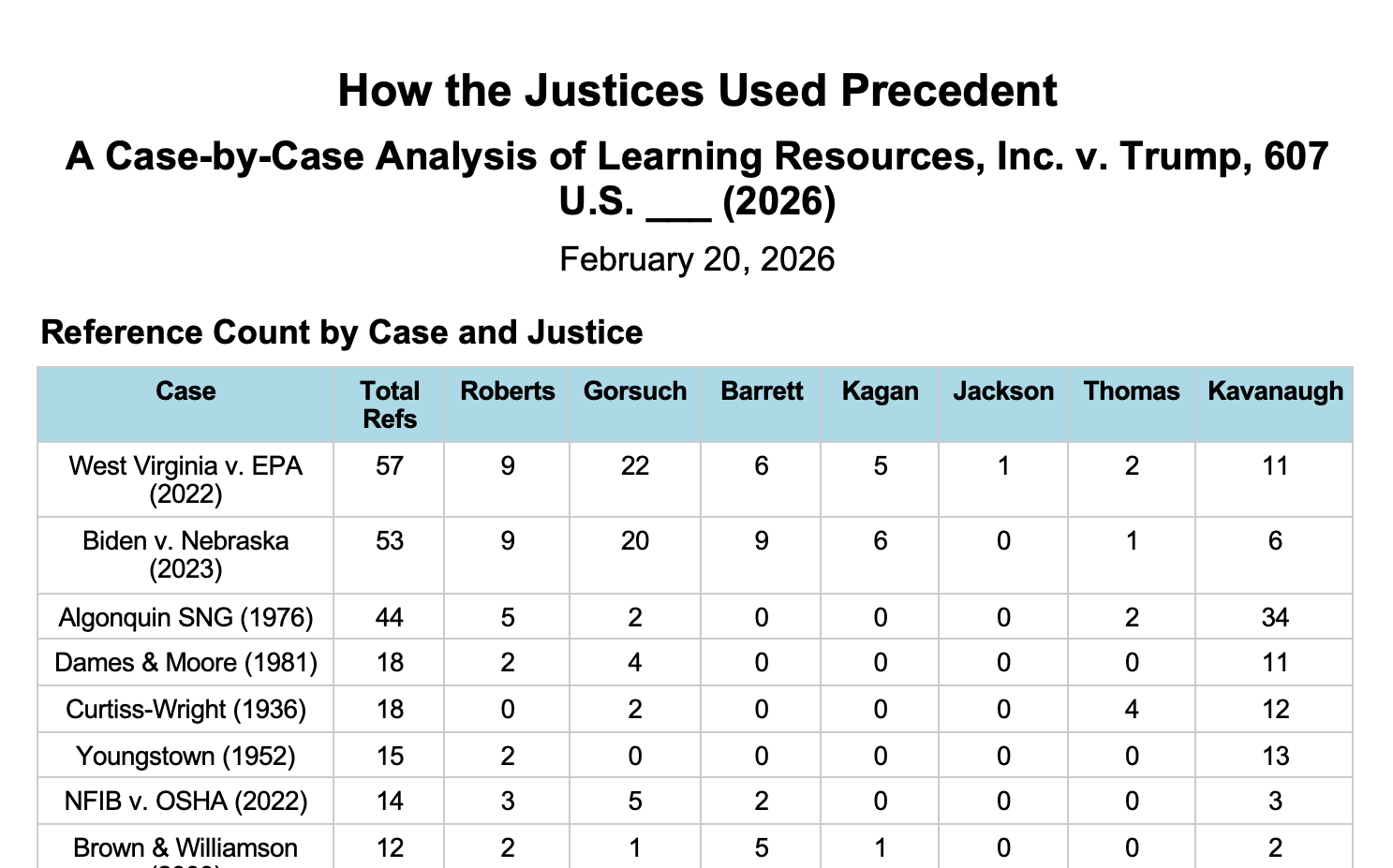

Notice that to request this output, I did not rely on whatever training data is inside of Claude. I relied on its ability to read the opinion and actually read the cited cases using its Midpage MCP capabilities (the Killer App). Claude came back with a table (shown immediately below) and a lengthy exposition. You can read the full analysis here.

I was then thinking I could use the material produced thus far to at least generate a lecture for my class the following week. So I asked the following:

The initial result did not have the right tone; it was somewhat patronizing and insufficiently scholarly. But after a second directive, I got something reasonably useful.

And now I got ambitious. I fed it a well-written Case Comment from the Harvard Law Review (thank you, Professor Kate Redburn) and provided the prompt below. It is not false humility to suggest that the degree of human insight provided to Claude was minimal.

Claude's first effort was not great. The article didn't have footnotes; an absence that would be fatal to any attempt at respectable publication. A corrective, however, produced something usable, though it still just did not quite look like a law review article. I then put the draft article through a synthetic "Word In Progress" seminar.

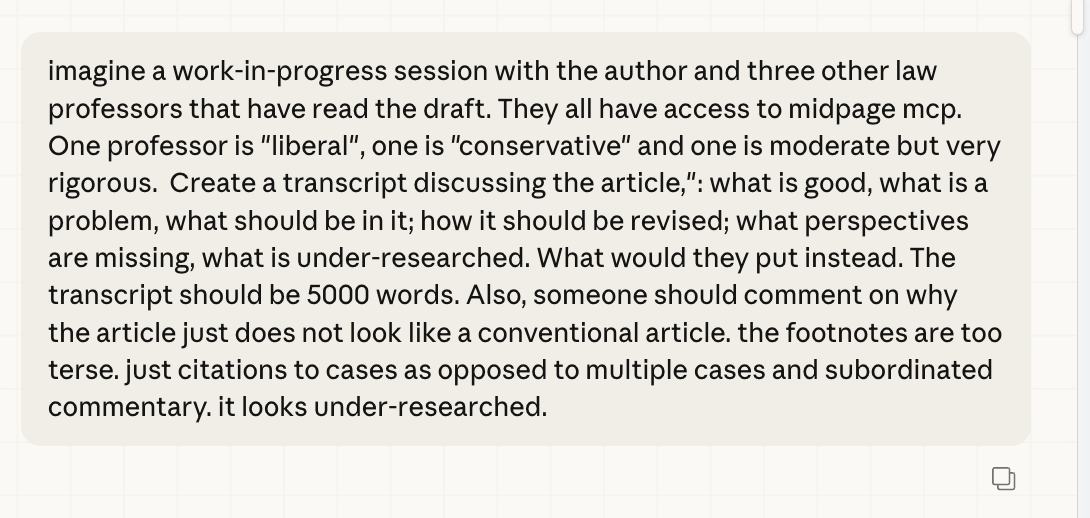

The result was as useful as some human "Works In Progress" sessions I have attended. Here's a sample of the full result:

I then engaged in classic meta-prompting:

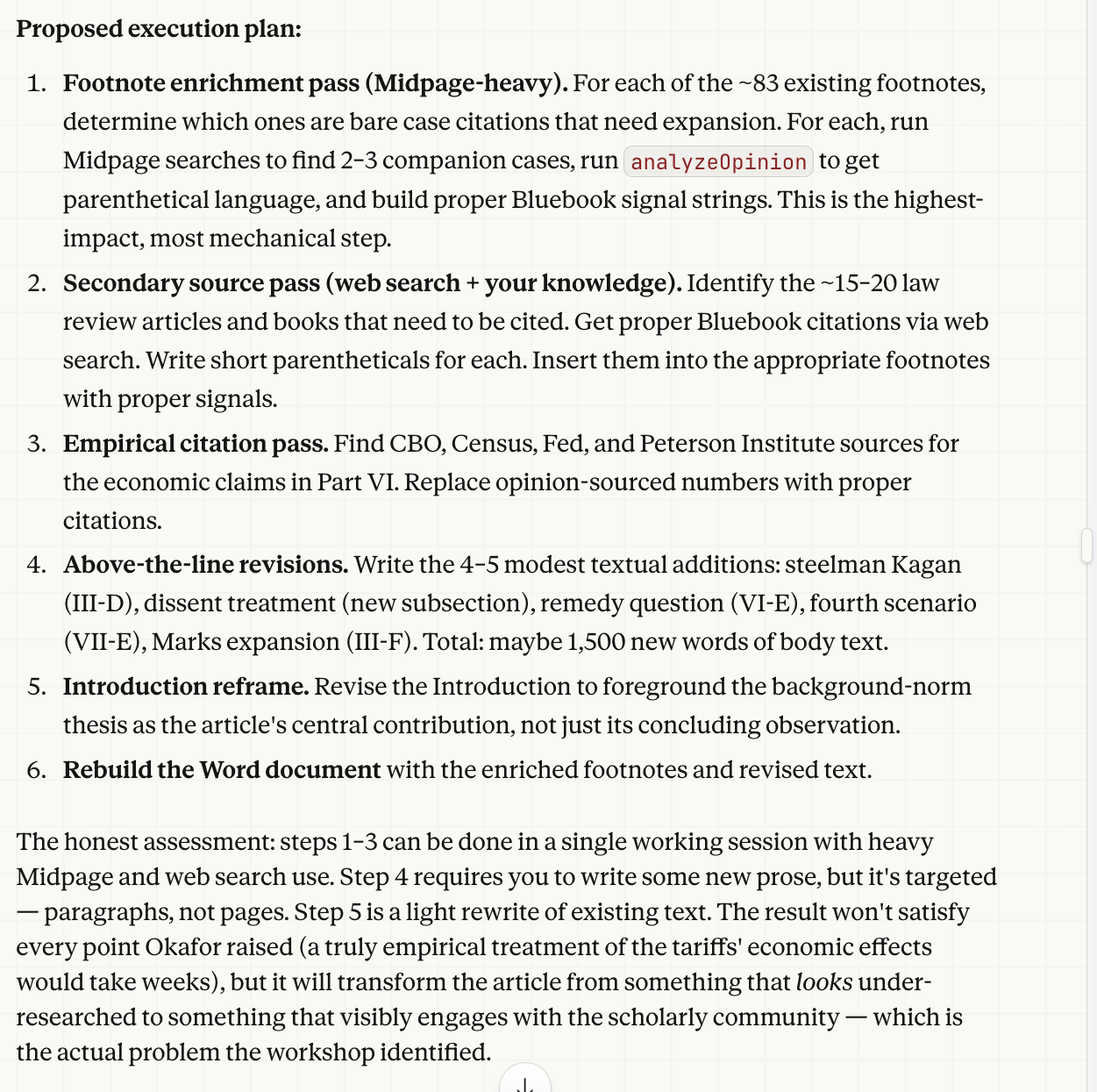

Claude indeed came up with a plan.

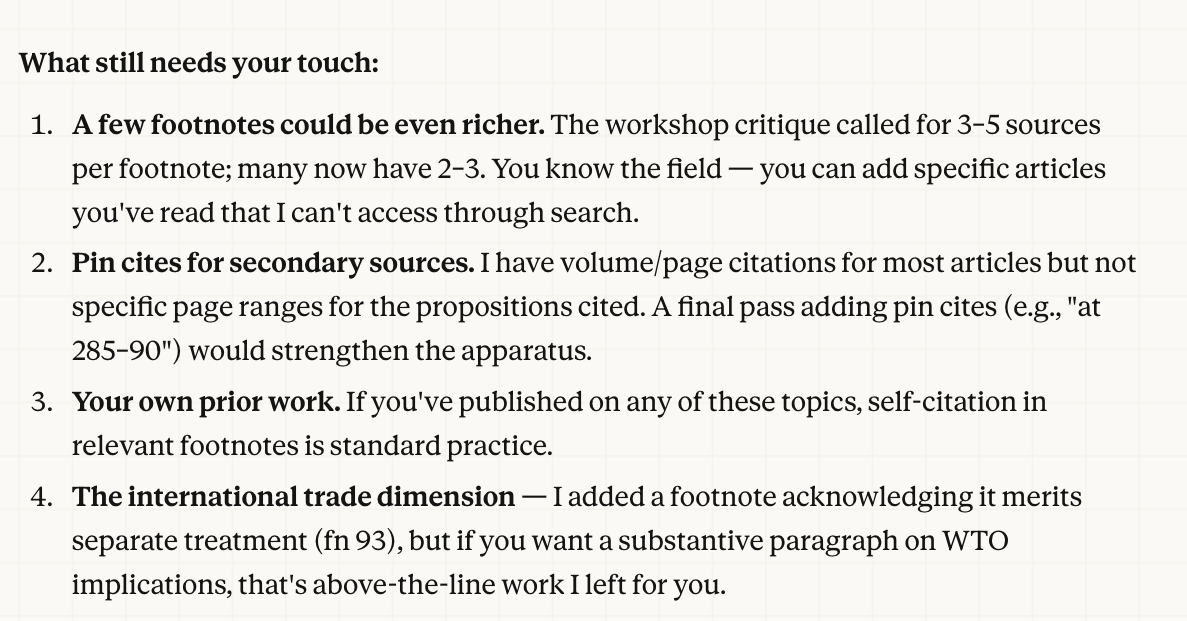

I let Claude churn and ran errands. When I returned, Claude told me it had produced an article but had left the following matters to me:

I am going to post the result on SSRN with a disclaimer that it was produced mostly by AI and see what feedback I receive. But you can read it here. Because of the limitations of the editing system used on this blogging platform, the footnotes have been converted to endnotes.

LEARNING RESOURCES, INC. v. TRUMP: THE TAXING POWER, THE MAJOR QUESTIONS DOCTRINE, AND THE PARADOX OF A LANDMARK THAT SETTLES LESS THAN IT SEEMS

THE SUPREME COURT — COMMENTS

2026 Term

Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump, 607 U.S. ___ (2026).

Recently, in Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump, the Supreme Court held six to three that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)[1] does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.[2] The decision invalidated what may be the most consequential unilateral economic action by a President in American history: a series of tariffs that at their peak imposed an effective rate of 145% on Chinese goods and covered imports from virtually every trading partner. The immediate practical stakes — approximately $129 billion in collected duties, ongoing refund litigation for over 301,000 importers[3], and the sudden unwinding of the executive branch's trade policy architecture — are enormous. But the doctrinal stakes, while superficially large, are more complicated. The six-Justice majority fractured over the role of the major questions doctrine, with only three Justices joining the plurality's major questions analysis. The Court's most ambitious constitutional reasoning — Justice Thomas's proposal to reclassify much of Article I as delegable non-core power, Justice Gorsuch's attempt to ground the major questions doctrine in centuries of common law — attracted no more than three votes apiece. The result is a paradox: an opinion of enormous practical consequence whose long-term doctrinal footprint may be smaller than the magnitude of the case would suggest.[4]

This Comment's central argument is that Learning Resources is best understood not as a case that transforms constitutional law but as one that reveals the major questions doctrine's evolution from a named doctrine requiring explicit invocation to a background interpretive norm that shapes statutory construction regardless of whether a majority of the Court is willing to invoke it by name. The statutory holding — that "regulate" does not include the power to tax — commanded all six votes in the majority and rests on straightforward textual and structural grounds. But the constitutional overlay that three Justices would have added did not attract majority support, and the ambitious theoretical positions staked out by individual Justices remain just that. The major questions doctrine emerges from Learning Resources with its theoretical foundations still contested and its applicability to foreign affairs and emergency powers still uncertain. The nondelegation doctrine emerges more fractured than before, with the Thomas-Gorsuch exchange revealing incompatible visions that may prevent the doctrinal revival commentators have anticipated since Gundy v. United States[5].[6] What the case does accomplish, however, is a decisive rejection of proposed exceptions to the major questions doctrine — for emergencies, for foreign affairs, and for statutes addressing "the most major of major questions" — that functions as a kind of background interpretive norm even without formal majority endorsement. And the practical consequences for the economy, for congressional-executive relations, and for the thousands of importers awaiting refunds will be substantial regardless of the opinion's doctrinal ambiguities.

The background norm thesis explains a puzzle in the opinion's reception. Commentators have struggled to reconcile the case's enormous practical significance with the narrowness of its formal holding. If all the Court held is that "regulate" does not mean "tax" — a proposition that seems almost self-evident — then why did the opinion run to hundreds of pages? Why did every Justice write separately? The answer this Comment proposes is that the formal holding is not the point. The point is the interpretive framework within which the holding was reached — a framework that, even without majority endorsement of the major questions label, constrains how future courts will read broad statutory delegations, particularly in the emergency and foreign affairs contexts. The long-term significance of Learning Resources may depend less on what the Court decided than on how Congress and the President respond.

This Comment also argues that the opinion's treatment of foreign affairs precedent — in particular, its narrow reading of Curtiss-Wright and its recharacterization of Dames & Moore — may prove more durable and more consequential than the major questions analysis that attracted more attention. These precedential moves were accomplished within the textual holding that all six majority Justices joined, giving them stronger institutional support than the plurality's constitutional overlay. And they address a dimension of executive power — the claim to special deference in foreign affairs — that extends well beyond the tariff context.

Part I of this Comment sets forth the factual and statutory background. Part II examines the majority's textual holding, which represents the opinion's most durable contribution. Part III analyzes the fractured treatment of the major questions doctrine, focusing on the three incompatible theories that emerged from the majority's concurrences and the paradoxical status of a doctrine that influenced the result without commanding a majority rationale. Part IV addresses the nondelegation debate between Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch, arguing that the exchange reveals a fundamental fracture in the anticipated pro-nondelegation coalition. Part V examines the opinion's treatment of foreign affairs precedent — particularly Curtiss-Wright, Dames & Moore, and the Youngstown framework — and argues that the majority's narrowing of these precedents may prove more consequential than the major questions analysis that attracted more attention. Part VI assesses the practical consequences and the likely political dynamics, arguing that the case's ultimate significance will turn on the congressional response. Part VII concludes.

I. BACKGROUND

A. The Constitutional Framework

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution vests in Congress the "Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.[7]" The placement of this power first among Congress's enumerated authorities was deliberate. Hamilton described the taxing power as "the most important of the authorities proposed to be conferred upon the Union.[8]" The Framers, having fought a revolution motivated in significant part by "taxation without representation," required all revenue bills to originate in the House of Representatives and vested no part of the taxing power in the Executive.[9] As Chief Justice Marshall established in McCulloch v. Maryland, the taxing power is a "power to destroy"[10]; as the Court later held in Nicol v. Ames, it is "the one great power upon which the whole national fabric is based.[11]"

The power to impose tariffs is "very clear[ly] . . . a branch of the taxing power.[12]" Marshall drew this distinction in Gibbons v. Ogden, explaining that while tariffs have a regulatory effect on commerce, they are exercises of the power to tax — a power "entirely distinct from the right to levy taxes" associated with the commerce power. This distinction, which was largely structural and definitional in Gibbons, becomes dispositive in Learning Resources.

The Government conceded at oral argument that the President enjoys no inherent authority to impose tariffs during peacetime[13] — a concession that establishes the constitutional baseline for the entire case. Whatever tariff authority the President claims must flow from a congressional statute. The question in Learning Resources was whether IEEPA was such a statute.

B. IEEPA and the Challenged Tariffs

Enacted in 1977 as a reform of the broader Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA)[14], IEEPA authorizes the President, upon declaring a national emergency involving an "unusual and extraordinary threat" originating primarily outside the United States, to take a series of economic actions. The key provision, 50 U.S.C.[15] § 1702(a)(1)(B), authorizes the President to "investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation or exportation of, or dealing in . . . any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest."

In early 2025, President Trump declared national emergencies with respect to illegal drug trafficking from Canada, Mexico, and China[16] and to "large and persistent" trade deficits. He invoked IEEPA to impose tariffs: a 25% duty on most Canadian and Mexican imports and a 10% duty on most Chinese imports to address drug trafficking, and a minimum 10% duty "on all imports from all trading partners[17]" — with dozens of nations facing higher rates — to address trade deficits. Over the following months, the President issued a dizzying series of modifications, at one point raising the effective tariff rate on Chinese goods to 145%.[18] The Government's statutory basis for all of these actions rested on two words separated by sixteen others in Section 1702(a)(1)(B): "regulate" and "importation."

Two sets of plaintiffs challenged the tariffs. The Learning Resources plaintiffs — two small businesses — sued in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, which denied the Government's motion to transfer the case to the Court of International Trade and granted a preliminary injunction, concluding that IEEPA did not grant the President the power to impose tariffs. The V.O.S. Selections plaintiffs — five small businesses and twelve States — sued in the Court of International Trade. That court granted summary judgment for the plaintiffs. The Federal Circuit, sitting en banc, affirmed in relevant part, concluding that IEEPA's grant of authority to "regulate . . . importation" did not authorize the challenged tariffs, which were "unbounded in scope, amount, and duration." Judge Cunningham concurred for four judges, reasoning that IEEPA did not authorize the President to impose any tariffs. Judge Taranto dissented for four judges, concluding that IEEPA authorized the challenged tariffs. The Supreme Court granted certiorari in both cases, consolidated them, and affirmed.

The jurisdictional question, though subsidiary to the merits, deserves brief mention. The Court agreed with the Federal Circuit that 28 U.S.C. § 1581(i)(1)[19] gives the Court of International Trade exclusive jurisdiction over civil actions "aris[ing] out of any law of the United States providing for . . . tariffs." Because the plaintiffs' challenges arose out of modifications to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule, the CIT had exclusive jurisdiction, and the D.C. District Court's judgment was vacated and remanded with instructions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. This jurisdictional holding has practical significance for the refund process: all claims for return of IEEPA duties must be channeled through the CIT, a specialized court with deep expertise in customs law but limited capacity to handle the volume of claims Learning Resources will generate.

II. THE TEXTUAL HOLDING: "REGULATE" DOES NOT INCLUDE THE POWER TO TAX

The most durable contribution of Learning Resources is its textual holding, set forth in Part II-B of the opinion[20] and joined by all six Justices in the majority, including Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson. The Court held that "regulate" does not include the power to tax.

The analysis proceeded along several reinforcing lines. First, the Court examined the ordinary meaning of "regulate" — "to fix, establish, or control; to adjust by rule, method, or established mode[21]" — and observed that while this definition captures much of what government does, it does not ordinarily encompass taxation. The Government could not identify any statute in which the power to "regulate" includes the power to tax, and the Court noted that the SEC, for example, cannot impose taxes on securities trading despite being authorized to "regulate the trading of . . . securities.[22]"

Second, the Court relied on congressional drafting practice. When Congress addresses both the power to regulate and the power to tax, it does so "separately and expressly.[23]" When Congress has delegated tariff authority specifically, it has consistently used words like "duty" — never relying on the term "regulate" alone — and has imposed caps on rates, durational limits, and procedural prerequisites including agency investigations and public hearings. IEEPA contained none of these features.

Third, the Court deployed the constitutional avoidance canon. Because IEEPA authorizes the President to "regulate . . . importation or exportation," reading "regulate" to include the power to tax would mean the President could tax exports — an action expressly forbidden by Article I, Section 9, Clause 5.[24]

Fourth, the Court invoked noscitur a sociis. "Regulate" is one of nine verbs in Section 1702(a)(1)(B). Combined with eleven objects, they authorize ninety-nine possible presidential actions — blocking imports, prohibiting transactions, nullifying property interests. None involves raising revenue. Tariffs are "different in kind, not degree" from the other authorities: they "operate directly on domestic importers to raise revenue for the Treasury.[25]"

Finally, the Court addressed the Government's reliance on Federal Energy Administration v. Algonquin SNG, Inc.[26], which had held that the power to "adjust the imports" under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act included the power to impose license fees. Justice Kavanaugh cited Algonquin thirty-four times — more than any Justice cited any case in the entire opinion.[27] But the majority distinguished Algonquin on two grounds: Section 232 contained sweeping discretion-conferring language ("take such action . . . as he deems necessary") that IEEPA lacks, and Section 232(a) explicitly referenced "duties," providing a statutory context that made it natural to read Section 232(b) as authorizing monetary exactions.[28]

This textual holding is, in many respects, unremarkable — which is precisely its strength. It does not depend on the major questions doctrine, the nondelegation doctrine, or any contested constitutional overlay. It rests on ordinary tools of statutory interpretation: dictionary definitions, congressional usage patterns, the avoidance canon, and contextual reading. That all six Justices in the majority joined it — including three who have been vocal critics of the major questions doctrine — underscores its solidity. Future challenges to other IEEPA actions will need to contend with the opinion's broader signals about the statute's scope, but the core holding that "regulate" does not include the power to tax is unlikely to be revisited.

C. The Migration of Precedent

The textual holding also illustrates a phenomenon that recurs throughout Learning Resources: the migration of precedent across doctrinal categories. The Court's invocation of McCulloch v. Maryland is instructive. In its original context, Marshall's description of the taxing power as a "power to destroy" was directed at the risk[29] of state taxation destroying federal instrumentalities — a federalism argument. Roberts repurposes the language for separation-of-powers ends, using it to underscore the magnitude of the taxing power and therefore the implausibility that Congress would delegate it through ambiguous statutory language. McCulloch is thus enlisted not for the proposition for which it was decided but for a characterization that gains new salience in a new doctrinal context. This is not unusual in constitutional adjudication — precedent migrates as the problems change — but the migration is worth noting because it reveals how the Court constructs authority for novel propositions.

The same phenomenon appears in the Court's use of Gibbons v. Ogden. Marshall's observation that tariffs are "very clear[ly] . . . a branch of the taxing power" was, in Gibbons[30], a distinction between the taxing power and the commerce power — an effort to define the boundaries of each in a federalism case about state regulation of interstate navigation. In Learning Resources, the same passage becomes a dispositive premise in a separation-of-powers case about the delegation of congressional authority to the President. The Court treats Marshall's characterization as a constitutional fact — tariffs are taxes — and builds its entire analytical structure on that foundation. The structural logic is elegant: because tariffs are taxes (Gibbons), and because the taxing power is uniquely Congress's (McCulloch, Nicol), and because Congress does not delegate its most important powers through vague language[31] (West Virginia), the President cannot find tariff authority in IEEPA's general power to "regulate . . . importation."

This chain of reasoning draws on cases decided in 1819, 1824, 1899, and 2022 — a remarkable span that illustrates the cumulative character of constitutional interpretation. But it also illustrates the constructed quality of the reasoning: each link in the chain involves a precedent used for purposes somewhat different from those for which it was originally articulated. Whether this is a strength (demonstrating deep constitutional continuity) or a vulnerability (revealing how flexible precedential reasoning can be) is itself a question the opinion raises but does not answer.

The Government also attempted a version of this migration, arguing that because tariffs have historically been discussed in connection with the Commerce Clause — and because "regulate" is a term closely associated with the commerce power — the power to "regulate . . . importation" naturally includes the power to impose tariffs. The majority rejected this argument, noting that it "answers the wrong question."[32] The issue was not whether tariffs can ever be a means of regulating commerce, but whether Congress, "when conferring the power to 'regulate . . . importation,' gave the President the power to impose tariffs at his sole discretion." Congressional pattern was plain: "When Congress grants the power to impose tariffs, it does so clearly and with careful constraints. It did neither here." The distinction between what tariffs are (a means of regulating commerce) and what the power to impose them is (a branch of the taxing power) is the hinge on which the entire case turns.

III. THE MAJOR QUESTIONS DOCTRINE: A PLURALITY THAT CASTS A LONG SHADOW

The more contested portion of the opinion is Part II-A-2, in which Chief Justice Roberts[33], joined only by Justices Gorsuch and Barrett, applied the major questions doctrine. Because only three Justices endorsed this analysis, it is technically a plurality opinion — not a holding of the Court. Yet its influence on the broader opinion and its implications for the doctrine's future are substantial.

A. The Plurality's Application

The plurality identified several features that triggered the major questions doctrine's heightened scrutiny. First, the purported delegation involved the "core congressional power of the purse[34]" — the taxing power, which belongs to Congress alone. This was a novel extension of the doctrine's reach: prior major questions cases had involved regulatory authority over private conduct (emissions standards, eviction moratoria, vaccine mandates), not the delegation of Congress's own enumerated fiscal powers.[35] By extending the doctrine to cover delegations of Congress's taxing authority, the plurality suggested that the major questions doctrine has a structural separation-of-powers dimension beyond its application to administrative agencies.

Second, the economic stakes were staggering. The Government itself boasted that the tariffs could generate trillions of dollars in revenue and that international agreements negotiated in reliance on the tariffs could be worth $15 trillion. These stakes "dwarf[ed] those of other major questions cases"[36] — West Virginia involved billions in compliance costs, Nebraska involved $430 billion in debt cancellation, but the IEEPA tariffs implicated the structure of global trade itself.

Third, the plurality emphasized the absence of historical precedent. In IEEPA's half century of existence, no President had ever invoked the statute to impose any tariffs. This "'lack of historical precedent,' coupled with the breadth of authority" claimed, was a "'telling indication'" that the tariffs exceeded the President's "legitimate reach."[37]

B. The Rejection of Exceptions

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the plurality's analysis was its rejection of two proposed exceptions to the major questions doctrine. The Government argued, first, that the doctrine should not apply to emergency statutes, because their "whole point" is to provide "substantial discretion to . . . respond to unforeseen emergencies.[38]" The plurality rejected this argument, citing Justice Jackson's warning in Youngstown that "emergency powers tend to kindle emergencies[39]" — noting that dozens of IEEPA emergencies remain ongoing, including the first, declared over four decades ago in response to the Iranian hostage crisis. The Government argued, second, that the doctrine should not apply, or should apply with reduced force, in the foreign affairs context. The plurality rejected this too: because the tariff power belongs to "Congress alone" during peacetime — as the Government itself conceded — foreign affairs implications do not make it more likely that Congress would have delegated that power through vague language. The plurality's conclusion — "There is no major questions exception to the major questions doctrine[40]" — is a memorable formulation that will recur in future litigation even though it appeared only in a plurality opinion.

C. Three Incompatible Theories

The most consequential feature of Learning Resources for the future of the major questions doctrine is not the plurality opinion itself but the three-way disagreement among the majority Justices about the doctrine's theoretical foundation.

Justice Gorsuch's concurrence offers the most ambitious version. He treats the major questions doctrine as a clear-statement rule grounded in Article I's Vesting Clause — a "substantive canon" external to any particular statute, designed to protect Congress's legislative power against executive aggrandizement. He traces its pedigree deep into common law, citing English courts that strictly construed corporate charters when corporations claimed extraordinary powers not expressly granted and common-law agency principles requiring clear authorization before agents could exercise extraordinary powers.[41] On this account, the major questions doctrine is not a judicial innovation but a restoration of centuries-old interpretive practice.[42] The implications are significant: if the doctrine is a freestanding constitutional rule, it operates independently of ordinary statutory interpretation and would require clear statements before any agency or executive officer could exercise transformative authority — regardless of how persuasive the textual arguments in their favor might otherwise be.

Justice Barrett joins the majority but resists Gorsuch's framing in a separate concurrence. She contends the doctrine is best understood as an ordinary application of textualism — reading statutory text in context, where constitutional structure is part of that context. She calls Gorsuch's strong-form clear-statement rule a "judicial flex"[43] in tension with the textualist commitment to reading statutes as written. Barrett's version is less ambitious but harder to distinguish from ordinary statutory interpretation — a vulnerability that Justice Kagan exploits.

Justice Kagan, joined by Justices Sotomayor and Jackson, takes a third position. She agrees that IEEPA does not authorize tariffs but insists the major questions doctrine is unnecessary because "ordinary principles of statutory interpretation lead to the same result.[44]" She applies what she describes as "straight-up statutory construction[45]" — text, context, and common sense about how Congress delegates — and concludes the Government's reading fails the normal test, not a heightened one.

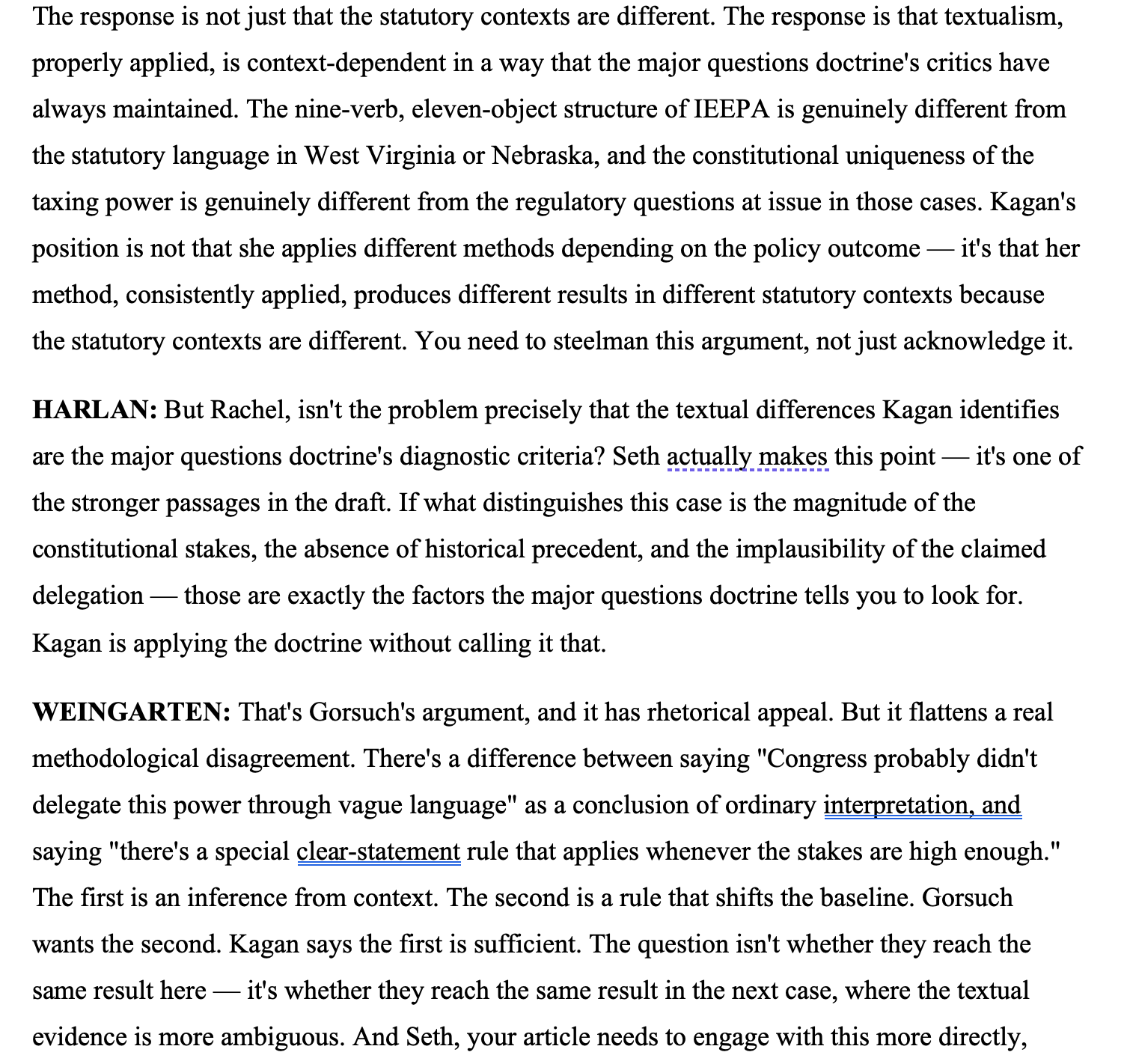

D. The Convergence Problem

Justice Gorsuch devotes several pages of his concurrence to what might be called the convergence problem — or, less charitably, the Kagan problem. He catalogs Justice Kagan's dissents[46] in West Virginia, Biden v. Nebraska, NFIB v. OSHA, and Alabama Association of Realtors. In each, Kagan read broad statutory language expansively in favor of executive power. "Safe and healthful working conditions" authorized a vaccine mandate for 84 million Americans.[47] "Regulations necessary to prevent the spread of communicable diseases" authorized a nationwide eviction moratorium.[48] "Waive or modify" authorized cancellation of $430 billion in student debt.[49] But "regulate . . . importation" — language at least as broad — does not authorize tariffs.

Gorsuch's argument has force. If Kagan's interpretive method consistently yields broad readings of delegations in contexts where she favors the policy outcome and narrow readings where she does not, then what she calls "context" may be, as Gorsuch puts it, "remarkably like the major questions doctrine[50]" — simply applied without the honest label. On this view, the major questions doctrine is not an extratextual thumb on the scale but a transparent accounting of an interpretive practice that all Justices employ when they perceive the stakes to be sufficiently high.

There is, however, a response available to Kagan, and it deserves more development than its surface simplicity might suggest. The statutory contexts are genuinely different — not merely in degree but in kind. IEEPA's nine-verb, eleven-object structure; the constitutional uniqueness of the taxing power; the complete absence of any reference to "duties," "tariffs," or revenue; the Export Clause problem — these features may distinguish this case from the prior major questions cases without any need for a heightened clear-statement requirement. More fundamentally, Kagan's position rests on a methodological commitment that textualism, properly applied, is context-dependent in a way that the major questions doctrine's proponents have resisted acknowledging. On this view, statutory interpretation always involves reading words in their full legal and constitutional context, and the interpretive weight of that context varies with the nature of the power claimed. The taxing power occupies a unique position in the constitutional structure — it is the first enumerated power, the subject of specific procedural requirements, and the historical catalyst for the Revolution itself. A textualist who reads "regulate . . . importation" in light of that constitutional background is not applying a special rule; she is doing what textualists always do, which is to read text in context. The fact that context produces different results in different cases is not evidence of inconsistency but of the method working as intended. If so, then the textual holding in Part II-B does the work, and the major questions analysis in Part II-A-2 is, as Kagan contends, surplusage.

The difficulty is that this response, however coherent as a methodological matter, concedes much of Gorsuch's analytical ground. If what distinguishes this case from West Virginia and Nebraska is the magnitude of the constitutional stakes, the absence of historical precedent for the claimed power, and the implausibility that Congress would delegate such extraordinary authority through ambiguous language — then those are precisely the major questions doctrine's diagnostic criteria, merely described in different vocabulary. The question is whether the relabeling matters. If it does — if there is a meaningful difference between an interpretive practice that is candidly identified as a clear-statement rule and one that is applied sub silentio under the rubric of "ordinary statutory construction" — then the theoretical debate has practical consequences. If it does not, then the major questions doctrine may be evolving into a background interpretive norm that shapes statutory construction regardless of whether a majority of the Court is willing to invoke it by name.

E. The Ideological Reversal

Learning Resources also marks a significant ideological reversal for the major questions doctrine. The doctrine's critics had long characterized it as a weapon deployed by conservative Justices against progressive regulatory initiatives — the EPA's climate regulations, the CDC's eviction moratorium, OSHA's vaccine mandate, the Department of Education's student loan program. Each of those cases involved a Democratic administration's exercise of delegated authority, and each was resolved by a conservative majority invoking the doctrine to limit that authority. The doctrine's ideological valence seemed clear: it was, in Justice Kagan's words, rooted in an "anti-administrative-state stance[51]" that prevented Congress from using agencies to do "important work."

Learning Resources scrambles this narrative. The major questions doctrine — or at least the interpretive principles that all six majority Justices applied, whatever label they attach — is now being used to constrain a Republican President's exercise of executive power over trade. The three liberal Justices, who dissented from every prior application of the doctrine, find themselves on the same side of the result. The three conservative dissenters (Kavanaugh, Thomas, Alito) — all of whom joined the majority in West Virginia and Nebraska — now find themselves arguing against the doctrine's application. The ideological symmetry is imperfect (Barrett and Gorsuch remain consistent supporters of the doctrine regardless of who occupies the White House), but the reversal is significant enough to complicate future characterizations of the doctrine as a one-directional tool.

Whether this ideological scrambling strengthens or weakens the doctrine is debatable. On one hand, the doctrine's bipartisan application may enhance its perceived legitimacy: if it constrains both Democratic agencies and Republican presidents, it is harder to dismiss as ideologically motivated. On the other hand, the fact that three Justices who consistently applied the doctrine in prior cases refused to apply it here — while three Justices who consistently opposed it effectively embraced its reasoning — may suggest that the doctrine functions less as a principled rule than as a results-oriented heuristic that each Justice applies selectively. The answer depends on whether one takes the Justices' stated reasoning at face value or reads the pattern of outcomes as revealing unstated preferences. Learning Resources provides evidence for both readings.

F. The Marks Problem

Learning Resources creates a significant Marks v. United States problem.[52] Under Marks, when the Court is fragmented, the holding is the position taken by the Justices who concurred in the judgment on the narrowest grounds. Here, six Justices agreed on the result. Three (Roberts, Gorsuch, Barrett) would have applied both the major questions doctrine and the textual analysis. Three (Kagan, Sotomayor, Jackson) would have applied only the textual analysis. The narrowest grounds are presumably the textual analysis alone — the Kagan position. But the practical question is whether lower courts will treat the plurality's rejection of emergency and foreign affairs exceptions as authoritative, even without majority endorsement. The plurality's analysis was joined by three Justices; it was not contradicted by any of the other three majority Justices, who simply declined to reach the issue. In a future case where the statutory text is more ambiguous — where the textual holding of Learning Resources does not control — the plurality's rejection of exceptions may carry significant persuasive weight even if it lacks binding force.

The circuit courts have developed divergent approaches to Marks opinions in which the concurring Justices simply decline to reach an issue rather than affirmatively rejecting the plurality's reasoning. The Third Circuit has treated silence as non-rejection, giving the plurality's uncontradicted reasoning precedential weight. The Ninth Circuit has applied a "logical subset" test that asks whether the concurrence's reasoning is a logical subset of the plurality's. The Fifth Circuit has taken a more restrictive approach, treating only points of actual agreement as binding. Learning Resources fits uncomfortably within all three frameworks because the Kagan concurrence neither endorses nor rejects the plurality's positions on emergency and foreign affairs exceptions — it simply finds them unnecessary. The resulting uncertainty will generate litigation in every circuit until the Court clarifies the binding force of its own fragmented analysis. This dual character of Learning Resources[53] — a clear statutory holding coexisting with an irresolvably fractured constitutional analysis — may itself represent an emerging pattern in separation-of-powers adjudication, in which the Court resolves immediate crises through narrow holdings while using concurrences to signal broader constitutional commitments that lack majority support.

G. The Dissent's Textual Case

Any assessment of Learning Resources must engage seriously with the dissent's strongest arguments, which are textual rather than structural. Justice Kavanaugh, joined by Justices Thomas and Alito, argued that "regulate . . . importation" is broad language that naturally encompasses conditions on importation[54], including monetary conditions. Kavanaugh emphasized congressional drafting practice from a different angle than the majority: Congress knew how to be specific when delegating tariff authority under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, but it also knew how to be broad, and IEEPA's sweeping language reflected a deliberate choice to provide the President with maximum flexibility in emergencies. Kavanaugh bolstered this reading with historical evidence: in the First Congress, tariffs were discussed as instruments of commercial regulation, not merely as revenue measures, and the power to "regulate commerce" was widely understood at the founding to include the power to impose duties on imports. The Taranto dissent in the Federal Circuit had made a similar argument, and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals in Yoshida had accepted a version of it.[55] If the original understanding of "regulate commerce" included the power to impose tariffs — and there is respectable historical scholarship supporting this claim — then "regulate . . . importation" has a more natural connection to tariff authority than the majority acknowledged.

The majority's response — that the question is not whether tariffs can ever be a means of regulating commerce but whether Congress delegated the tariff power through IEEPA's specific language — is persuasive. But the dissent's argument is not frivolous, and its implications extend beyond this case. If broad statutory language like "regulate" can never encompass taxation absent explicit textual signals, then the interpretive principle the majority established constrains not just IEEPA but every statute that uses "regulate" in contexts where monetary exactions might serve regulatory purposes. The scope of this principle — whether it is limited to the unique constitutional status of the taxing power or extends more broadly to any claim that "regulate" encompasses monetary burdens — is a question Learning Resources raises but does not answer.

IV. THE NONDELEGATION FRACTURE

One of the most unexpected developments in Learning Resources was the exchange between Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch over the nondelegation doctrine — an exchange that revealed a fundamental incompatibility within the coalition that has been expected, since Gundy v. United States, to reinvigorate the doctrine.

A. Thomas's "Core Legislative Power" Theory

Justice Thomas has long maintained that the nondelegation doctrine is rooted not only in the Vesting Clause of Article I but also in the Due Process Clause, and that it applies only to "core legislative power" — the power to make rules setting conditions for deprivations of life, liberty, or property.[56] In Learning Resources, Thomas applied this theory to its logical conclusion. He argued that most of Article I, Section 8's enumerated powers — including the powers to borrow money, declare war, support armies, and regulate foreign commerce[57] — are not "core legislative power" in his sense. They are former prerogative powers of the Crown that the Framers assigned to Congress for institutional reasons but that may be delegated back to the President without constitutional infirmity. The tariff power is one such power. Thomas contended that importing was a "privilege" at the founding, not a "right," and that imposing duties on imports therefore does not deprive anyone[58] of "life, liberty, or property."

The implications are breathtaking. If Thomas's theory prevailed, Congress could delegate entire categories of enumerated powers — the war power, the borrowing power, the tariff power, the coinage power — permanently and without constraint to the President. The nondelegation doctrine would police only the subset of legislative activity that touches on individual liberty. This would simultaneously narrow the nondelegation doctrine's scope and vastly expand presidential power — a combination that is doctrinally innovative but constitutionally unsettling.

B. Gorsuch's Rebuttal

Justice Gorsuch's concurrence devotes extensive attention to dismantling Thomas's theory. His argument proceeds on three levels. First, textual: Article I, Section 1 vests "all legislative Powers" in Congress, without differentiating[59] between "core" and "non-core" varieties. Second, historical: the Founders themselves described powers Thomas would classify as "non-legislative" — including the tariff power, the power to raise armies, and the power to coin money — as "legislative powers."[60] Third, evidence from early practice: in the Second Congress, the House rejected on nondelegation grounds a proposal to give the President unfettered power to establish postal routes — even though doing so would hardly touch on life, liberty, or property.[61]

C. The Fractured Coalition

This exchange is consequential because it shatters the apparent five-Justice majority for reinvigorating the nondelegation doctrine. After Gundy, where Justice Gorsuch's dissent articulated a strict nondelegation standard[62] and Justices Thomas and Alito signaled agreement, commentators widely assumed that Justice Kavanaugh's subsequent statements of sympathy[63] created a five-Justice majority waiting for the right case. Learning Resources reveals that this assumption was wrong — or at least premature. Thomas's narrow "core legislative power" theory and Gorsuch's broad "all legislative powers" theory are incompatible in application. Thomas would permit delegation of the tariff power, the war power, and the borrowing power; Gorsuch would subject all of them to nondelegation scrutiny. Even if five Justices support strengthening the nondelegation doctrine in principle, they cannot agree on what the strengthened doctrine would look like. This fracture may delay or prevent the doctrinal revival that has hung over administrative law since 2019.

The irony is palpable. The case most likely to bring the nondelegation question to the Court — a challenge to Congress's delegation of tariff authority under IEEPA — instead exposed the internal contradictions within the pro-nondelegation coalition. The nondelegation doctrine thus emerges from Learning Resources weaker, not stronger, as a practical matter — even though at least three Justices (Gorsuch, Thomas, and presumably Kavanaugh) continue to favor its reinvigoration in some form.

D. The Intelligible Principle's Quiet Survival

One notable feature of the nondelegation exchange is what it reveals about the survival of the intelligible principle test — the standard articulated in J.W. Hampton[64], Jr. & Co. v. United States, which has governed delegation challenges since 1928. Under Hampton, Congress need only provide an "intelligible principle" to guide the executive's exercise of delegated authority. The test is notoriously permissive: the Court has not struck down a statute on nondelegation grounds since 1935.[65]

In Gundy, Justice Gorsuch proposed replacing the intelligible principle test with a more demanding standard that would require Congress itself to make the important policy decisions, leaving the executive only to "fill up the details.[66]" The assumption after Gundy was that the Hampton test was living on borrowed time. Learning Resources suggests otherwise. Neither the majority nor any individual Justice endorsed a replacement for the intelligible principle test. Thomas proposed narrowing the nondelegation doctrine's scope rather than strengthening its standard. Gorsuch defended the doctrine vigorously but in the context of a case that was ultimately resolved on statutory rather than constitutional grounds. And Kavanaugh, whose vote was thought to be the fifth for nondelegation revival, dissented on the ground that IEEPA's text authorized the tariffs — without reaching the nondelegation question at all.

The intelligible principle test thus survives Learning Resources intact, if somewhat awkwardly. It was not discussed, not applied, and not replaced. The Justices who would like to strengthen it cannot agree on how, and the Justices who would like to abandon it were not called upon to defend it. The test remains the law — not because anyone affirmatively endorsed it, but because no coalition could form around an alternative. For practitioners advising clients on the validity of congressional delegations, this quiet survival may be the most practically significant nondelegation development in the case.

V. FOREIGN AFFAIRS PRECEDENT: THE QUIET NARROWING

The least noticed but potentially most consequential aspect of Learning Resources is the majority's treatment of three pillars of presidential foreign affairs power: United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., Dames & Moore v. Regan, and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

A. Curtiss-Wright Reined In

Justice Sutherland's 1936 opinion in Curtiss-Wright has long occupied an outsized role in debates over presidential foreign affairs power. His description of the President as the "sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations,[67]" and his suggestion that "strict limitation upon congressional delegations of power to the President over internal affairs does not apply with respect to delegations of power in external affairs,[68]" have been cited by successive administrations to justify broad executive action abroad.

Justice Kavanaugh's dissent in Learning Resources cited Curtiss-Wright twelve times, arguing that courts should apply "routine textualist statutory interpretation[69]" in the foreign affairs context without any major-questions thumb on the scale. The majority responded not by overruling Curtiss-Wright but by reading it narrowly. Justice Gorsuch emphasized that the statute at issue in Curtiss-Wright was far more constrained than IEEPA: it authorized the President to prohibit arms sales to specific countries in a specific conflict after making a specific factual finding. Whatever Sutherland's sweeping dicta might mean, the actual holding involved a carefully bounded delegation.[70] This narrow reading aligns with decades of scholarly criticism, most notably Charles Lofgren's seminal 1973 article[71] arguing that Sutherland's opinion conflated the President's diplomatic role with substantive lawmaking authority. By treating Curtiss-Wright's broadest language as nonbinding dicta, the majority diminished its utility for future executive power claims without creating the doctrinal upheaval of an overruling.

B. Dames & Moore as a Case About IEEPA's Limits

The majority's treatment of Dames & Moore v. Regan is equally significant. Dames & Moore has been widely understood as a case about executive flexibility in foreign affairs emergencies — the Court's willingness to uphold presidential action on the basis of congressional acquiescence and historical practice, even in the absence of clear statutory authorization. Justice Kavanaugh invoked this reading, arguing that the 1981 Court blessed presidential action under IEEPA despite textual ambiguity.

The majority turned Dames & Moore against the Government. Roberts noted that the 1981 opinion disclaimed any "general guidelines" for other situations — no fewer than five times.[72] More importantly, the majority emphasized that Dames & Moore actually held that "the terms of IEEPA do not authorize" the President[73]'s action — the suspension of claims against Iran. The Court upheld the President's actions only because he had independent authority to enter into executive agreements. Roberts repurposed this language: "So too here; the terms of IEEPA do not authorize tariffs.[74]"

This is a remarkable recharacterization. Dames & Moore, which for decades had been cited as authority for flexible executive power in emergencies, is transformed into a case about the limits of IEEPA — a reading that constrains rather than expands presidential authority. Whether this transformation will hold in future cases — particularly cases involving executive action that, unlike tariffs, falls within the traditional scope of IEEPA's sanctions-related authorities — remains to be seen. But the reframing itself is a significant doctrinal development.

C. Both Sides Claim Jackson

The Youngstown framework pervades the Learning Resources opinions, but neither side can claim it definitively. Kavanaugh frames the case as Youngstown Category One: the President acting pursuant to congressional authorization, where presidential power is at its zenith.[75] The majority effectively treats it as a case where the claimed authorization does not exist, placing the President somewhere between Category Two and Category Three.

Both sides invoke Justice Jackson — selectively. Roberts quotes Jackson's warning that "emergency powers tend to kindle emergencies[76]." Kavanaugh[77] quotes Jackson's footnote recognizing that delegation constraints should be relaxed in external affairs.[78] That both sides can claim Jackson illustrates the internal tensions within the Youngstown concurrence itself — tensions that have been present since 1952 but that Learning Resources has forced into open confrontation.

The deeper problem is that Youngstown's three categories presuppose agreement on a logically prior question: what counts as congressional authorization. If IEEPA authorizes tariffs, the President is in Category One — acting with both his own authority and whatever power Congress can delegate. If IEEPA does not, the President is in Category Two or even Category Three, depending on whether one reads the Constitution's vesting of the tariff power in Congress as an implicit prohibition on its exercise by the Executive. The Youngstown framework offers no guidance on the threshold question of whether the statutory authorization exists; it merely tells the court what follows from the answer. In a case where the statutory question is the whole dispute, Youngstown's categories are less a framework for analysis than a vocabulary for announcing conclusions.

This is not to say Youngstown is useless in Learning Resources — Jackson's observations about emergency powers and the danger of executive overreach are directly relevant and are quoted by the majority to powerful effect. But Learning Resources reveals the framework's limitations as a decision procedure. Jackson designed his three categories for a case where the statutory question was clear (no statute authorized the steel seizure) and the constitutional question was hard (did the President have inherent authority?). In Learning Resources, the statutory question is the hard one, and the constitutional question — whether the President has inherent peacetime tariff authority — was conceded away. The categories apply, but they do not do the analytical work. The real work is done by the textual analysis and, for three Justices, the major questions doctrine. Youngstown provides the stage set but not the script.

VI. PRACTICAL CONSEQUENCES AND POLITICAL DYNAMICS

A. The Immediate Economic Impact

The practical consequences of Learning Resources are staggering and immediate. As of December 2025, U.S. Customs and Border Protection had collected approximately $129 billion in duties under IEEPA[79] from more than 301,000 importers across 34 million customs entries. That money was collected under a statute the Court has now held does not authorize tariffs.

The refund landscape is complex. Over 2,000 companies filed protective refund suits with the Court of International Trade before the ruling, positioning them to recover their duties with statutory interest. The CIT's exclusive jurisdiction over these claims, which the Court confirmed in Learning Resources itself, means that a single specialized court will manage the largest refund operation in customs history.[80] Companies that did not file protective suits face a more uncertain path. Customs entries typically liquidate within 314 days; entries that have already liquidated may be permanently barred from administrative refund absent congressional intervention. The stakes for individual importers — particularly small businesses that paid duties without the resources to file protective litigation — are substantial.

The ruling does not strip the President of all tariff authority. Tariffs imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act — on steel, aluminum, automobiles, and certain pharmaceuticals — remain in force. So do tariffs on Chinese goods imposed under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. But those statutes impose procedural prerequisites, agency investigations, and caps on duration or amount that IEEPA lacked.[81] The era of overnight, unlimited, unilateral tariff authority under emergency powers is over.

Supply chains that had been restructured in response to the IEEPA tariffs — with manufacturers shifting production out of China, rerouting imports through third countries, and absorbing cost increases — now face the prospect of another round of dislocation. Firms that made costly investments to comply with the tariff regime may find those investments wasted. The uncertainty itself imposes costs: businesses cannot plan capital expenditure, negotiate long-term supply contracts, or make hiring decisions without knowing whether the tariffs will be reinstated through alternative legal mechanisms.

For trade-dependent regions, the effects are concentrated. The Port of Houston, the nation's largest port by total tonnage, processes approximately $291 billion in annual trade. Texas's manufacturing sector exported over $375 billion in goods in the year before the tariffs were imposed. Houston's energy sector faces particular vulnerability: the IEEPA tariffs had triggered retaliatory measures from trading partners that threatened LNG exports and petrochemical products — retaliation that may now unwind, but on an uncertain timeline.

B. The Congressional Response

The most consequential question going forward is how Congress will respond. The Court's holding effectively returns the tariff power to Congress, which must now decide whether, and on what terms, to grant the President the authority he claimed under IEEPA. Several dynamics are worth noting.

First, any new delegation of tariff authority will be drafted in the shadow of Learning Resources. If the major questions doctrine applies — as three Justices believe and as the background interpretive norm may effectively require — then Congress will need to speak clearly and with reasonable constraints. Vague language delegating the power to "regulate" or "adjust" imports will not suffice. Congress will need to specify the circumstances under which tariffs may be imposed, the rates or rate caps, the durational limits, and the procedural prerequisites. The opinion thus does not merely resolve a dispute; it restructures the bargaining dynamic between the branches by raising the legislative specificity that courts will demand.

Second, the political dynamics are unusual. The IEEPA tariffs had divided the President's own party: some Republican members of Congress supported the tariffs as a tool of trade policy, while others — particularly those representing agricultural, manufacturing, and retail constituencies — objected to the economic disruption and the absence of congressional input. Learning Resources may paradoxically provide political cover for members who opposed the tariffs but were reluctant to challenge the President directly. The Court, rather than Congress, has imposed the constraint — a dynamic that echoes the political function of judicial review in other separation-of-powers contexts.

Third, the President retains alternative statutory pathways. Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 authorizes the U.S. Trade Representative to impose tariffs in response to unfair trade practices, subject to investigation, consultation, and publication requirements. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act authorizes tariffs to protect national security, subject to Commerce Department investigation and reporting. The President has reportedly directed the initiation of new Section 301 investigations, but those processes take a minimum of nine months. The gap between Learning Resources and the availability of alternative tariff authority creates a window of policy uncertainty that will itself have economic consequences.

C. The Refund Mechanics

The mechanics of the refund process deserve attention because they will generate a second wave of litigation. Companies that filed protective suits in the Court of International Trade are in the strongest position, as they have preserved their claims and can seek reliquidation with interest. The CIT's exclusive jurisdiction — confirmed by the Court in Learning Resources — means that federal district courts cannot entertain refund actions, channeling all claims through a single specialized tribunal.

For companies that did not file protective suits, the path is harder. Under 19 U.S.C.[82] § 1514, an importer must protest a customs liquidation within 180 days; unliquidated entries may be protested after the ruling, but liquidated entries are generally final. Whether the Government will offer administrative relief — through reliquidation orders, regulatory guidance, or some other mechanism — is unclear. The political pressure to provide refunds will be substantial, but the legal mechanisms are constrained. Congressional action may be necessary to authorize retroactive relief for importers who did not file timely protests.

D. The Yoshida Problem and Statutory Lineage

One further dimension of the foreign affairs and statutory debate merits attention. The Government relied heavily on United States v. Yoshida International, Inc., a 1975 decision of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, in which that court held that the power to "regulate . . . importation" under TWEA[83] — IEEPA's predecessor — authorized President Nixon to impose a temporary 10% import surcharge. The Government argued that when Congress enacted IEEPA in 1977, it was aware of Yoshida and therefore incorporated that interpretation into the new statute.

The majority's treatment of Yoshida is notable for its skepticism toward arguments from statutory lineage. The Court acknowledged its general practice of assuming that Congress incorporates well-settled judicial definitions into subsequent legislation, but held that "a single, expressly limited opinion from a specialized intermediate appellate court does not clear that hurdle.[84]" The Court further noted that the Nixon tariffs upheld in Yoshida were "far removed" from IEEPA[85]'s "original purposes" of sanctioning foreign belligerents, and that the tariffs themselves were limited in amount (10%, capped at congressionally authorized rates), duration (less than five months), and scope (only goods that had been the subject of prior tariff concessions). The current IEEPA tariffs — unlimited in amount, indefinite in duration, and universal in scope — bore no resemblance to the "expressly limited" action Yoshida had endorsed.

This is a significant methodological holding in its own right. Courts frequently rely on statutory lineage arguments — the claim that Congress, by reenacting similar language, endorsed the prior interpretation of that language. The Court's refusal to extend Yoshida through TWEA to IEEPA establishes a meaningful constraint on this mode of reasoning: a single decision from a specialized court, addressing limited and unusual facts, does not establish the kind of "broad and unquestioned judicial consensus[86]" necessary to conclude that Congress incorporated a judicial definition into statutory text. This constraint has implications well beyond the tariff context. In any case where the Government argues that Congress "must have known" about a lower-court interpretation when it enacted or reauthorized a statute, Learning Resources' demanding standard — requiring a "well-settled" meaning, not merely an isolated precedent — will provide ammunition for challengers.

VII. ASSESSMENT: A LANDMARK THAT SETTLES LESS THAN IT SEEMS

Learning Resources is unquestionably an important case. It resolved a live constitutional crisis — the exercise of the taxing power by the Executive without clear congressional authorization — and its practical consequences for the American economy are enormous. But from a doctrinal perspective, the case settles less than its magnitude might suggest.

A. What the Case Establishes

The opinion's most durable contributions are its textual holding and its rejection of proposed exceptions. The holding that "regulate" does not include the power to tax is solid, commands six votes, and rests on uncontroversial interpretive tools. It will foreclose future attempts to read IEEPA as authorizing tariffs. It also establishes, at a higher level of generality, that the word "regulate" in federal statutes should not be read to encompass taxation absent clear contextual signals — a principle with potential application beyond the IEEPA context.

The rejection of emergency and foreign affairs exceptions to the major questions doctrine, while technically a plurality holding, may function as a background norm that shapes future litigation. No Justice in the majority disagreed with these conclusions; three simply declined to reach the issue. In a future case where the major questions doctrine is squarely presented and a majority applies it, the plurality's reasoning in Learning Resources will provide the framework[87] for evaluating claims that the doctrine should yield to emergency or foreign affairs considerations.

B. What the Case Does Not Establish

The case does not establish the theoretical foundation of the major questions doctrine. Three Justices treat it as a clear-statement rule grounded in constitutional structure (with Gorsuch and Barrett themselves disagreeing on the precise nature of that grounding). Three Justices reject the doctrine as unnecessary surplusage. Three Justices (in dissent) contend the doctrine should not have been applied at all. This three-way fracture means that the next major questions case will revisit the same foundational questions Learning Resources raised but did not resolve: Is the doctrine a freestanding constitutional rule? A contextual interpretive norm? Or an illegitimate judicial invention?

The case does not establish the scope or revival of the nondelegation doctrine. Justice Thomas's attempt to limit the doctrine to "core legislative power" attracted no additional votes. Justice Gorsuch's robust defense of a broad nondelegation principle also attracted no additional votes. The apparent five-Justice pro-nondelegation coalition remains fractured, and Learning Resources provides no path to reconciliation.

The case does not establish the "metes and bounds" of the President's remaining authority under IEEPA. The Court expressly declined to define the limits of the power to "regulate . . . importation" outside the tariff context. Whether the President can impose import quotas, licensing requirements, or embargoes under IEEPA remains an open question. The Court's textual analysis provides some guidance — the nine verbs and eleven objects suggest a range of permissible actions short of taxation — but the precise boundaries will be worked out in future cases.

C. The Background Norm Effect

Even where Learning Resources fails to establish formal holdings, it may accomplish something subtler: the creation of background norms that constrain future interpretation without the force of precedent. The plurality's rejection of emergency and foreign affairs exceptions to the major questions doctrine is the clearest example. These propositions — "There is no major questions exception to the major questions doctrine[88]"; emergency powers "tend to kindle emergencies" and therefore deserve more skeptical, not less skeptical, judicial review; the foreign affairs implications of a statute do not make it more likely that Congress would delegate its taxing power through vague language — did not attract a majority. But they were not contradicted by any member of the majority. The Kagan concurrence does not say that the major questions doctrine should yield to emergency or foreign affairs considerations; it simply says the doctrine is unnecessary in this case.

The result is an asymmetry: three Justices have endorsed these propositions, three have declined to address them, and none has rejected them. In future litigation, the Government will bear the burden of persuading at least one of the three declining Justices to affirmatively reject the propositions — a harder task than simply asking for their continued silence. Meanwhile, lower courts, which must navigate fragmented Supreme Court opinions using whatever guidance is available, will likely treat the plurality's reasoning as highly persuasive even if not binding.

This background norm effect may prove to be Learning Resources' most significant contribution to the major questions doctrine's development. The doctrine's formal status — its vote count, its theoretical grounding, its precedential force — remains contested. But its practical effect as an interpretive norm that shapes how courts read broad statutory delegations is increasingly entrenched. Learning Resources did not create this norm; West Virginia and Nebraska did. But Learning Resources extended the norm's reach into two new domains — emergency powers and foreign affairs — where the Government had argued it should not apply. Even as a plurality holding, that extension may prove irreversible in practice.

D. The Paradox of Doctrinal Modesty

There is a paradox at the heart of Learning Resources. The case presented the most dramatic confrontation between Congress and the President over the taxing power in modern American history. It implicated foundational questions about the major questions doctrine, the nondelegation doctrine, and the scope of presidential foreign affairs power. Every Justice wrote at least one opinion. The decision runs to hundreds of pages. And yet, at the end of all this, the holding that commands six votes is a straightforward piece of statutory interpretation: "regulate" does not mean "tax."

This may not be a weakness. The canonical separation-of-powers cases — Youngstown, INS v. Chadha, Clinton v. City of New York[89] — often resolved immediate crises through holdings that were narrower than the rhetoric surrounding them. Youngstown's most enduring legacy is not its specific holding about steel seizure but Justice Jackson's concurrence, which was dicta. Chadha's broad reasoning[90] about presentment and bicameralism has been cabined by subsequent practice. Clinton v. City of New York's invalidation[91] of the line-item veto resolved a specific institutional arrangement without establishing a broader theory of legislative power. Learning Resources may follow a similar pattern: the immediate crisis is resolved through a narrow textual holding, while the broader constitutional questions — the scope of the major questions doctrine, the future of nondelegation, the limits of Curtiss-Wright — continue to develop in future cases.

There is, however, an alternative reading. Perhaps the paradox of doctrinal modesty is not a bug but a feature of a Court that is genuinely uncertain about the theoretical foundations of the doctrines it is developing. The major questions doctrine is only four years old as a named doctrine; its theoretical basis remains unsettled, as the three-way debate among the majority Justices demonstrates. The nondelegation revival has been anticipated for seven years but has not materialized. The Court may be proceeding cautiously — resolving cases on the narrowest available grounds — precisely because the Justices are not ready to commit to the broader theories their concurrences and dissents explore. If so, then Learning Resources is not a case that fails to live up to its potential; it is a case that accurately reflects the current state of the Court's thinking: six Justices who agree on the result and the textual reasoning, but who cannot yet agree on why the broader constitutional principles matter or how they should be formulated.

The case is perhaps best understood not as a landmark that transforms constitutional law but as a consolidating opinion that confirms existing boundaries while declining to extend them. The major questions doctrine is neither expanded nor contracted; it is applied by three Justices and functionally embedded in the reasoning of three others who refuse to call it by its name. The nondelegation doctrine is neither revived nor abandoned; it is debated by two Justices whose incompatible visions ensure that the debate will continue. The foreign affairs precedents are neither overruled nor reaffirmed; they are narrowed in ways that constrain future executive power claims without formally displacing the broad principles they articulated.

E. The Political Economy of Learning Resources

The ultimate significance of Learning Resources will turn on events outside the Court's control. Three scenarios are plausible, and each carries different implications for the case's long-term significance.

In the first scenario, Congress grants the President new tariff authority in legislation that specifies clear terms and reasonable constraints — rate caps, durational limits, procedural prerequisites, and defined emergency triggers. This is the scenario the plurality opinion effectively invites, and it would represent the most constructive institutional outcome. Learning Resources would have served as a course correction: channeling executive power through the legislative process, forcing Congress to take responsibility for trade policy rather than outsourcing it to the President under cover of a vague emergency statute, and ensuring that the delegation of tariff authority satisfies the specificity norms the Court has articulated. In this scenario, the case would be remembered as a vindication of the separation of powers — not because it permanently stripped the President of tariff authority, but because it required that authority to flow through proper legislative channels.

In the second scenario, Congress deadlocks. The political dynamics make this plausible: Democratic members may be reluctant to grant new tariff authority to a Republican president, while Republican members may be divided between those who support the tariffs and those who oppose the economic disruption they caused. If no legislation passes, the tariff regime is not replaced, and the practical consequences of Learning Resources — disruption to supply chains, uncertainty for businesses, the unwinding of trade agreements negotiated in reliance on the tariffs, and a potential shift in the global trading order — become the case's primary legacy. In this scenario, Learning Resources would be remembered less as a constitutional landmark than as an economic inflection point — the moment the legal architecture supporting the Administration's trade policy collapsed.

In the third scenario, the President pursues alternative statutory pathways under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, and the resulting tariff actions are challenged in court. This scenario would generate a second round of litigation in which Learning Resources' textual analysis and its background norm against broad readings of delegated tariff authority shape the outcome. The Government would need to demonstrate that the specific statutory language of Section 301 or Section 232 clearly authorizes the tariffs it seeks to impose — a showing that the procedural prerequisites, agency investigations, and scope limitations built into those statutes should make easier than under IEEPA, but that may still prove contested at the margins.

A fourth scenario deserves attention: that the executive branch seeks to circumvent Learning Resources through creative reinterpretation rather than accept it as a constraint. The history of executive branch responses to adverse separation-of-powers rulings is a history of institutional adaptation. After the Court invalidated the legislative veto in INS v. Chadha, Congress developed alternative oversight mechanisms — including report-and-wait provisions, joint resolutions of disapproval, and appropriations riders — that achieved functionally similar results.[92] After the Court struck down the line-item veto in Clinton v. City of New York, presidents expanded their use of signing statements and executive orders to achieve item-by-item control over spending. In the trade context, the President might pursue creative uses of procurement rules, export controls, or regulatory mechanisms to impose costs on imports functionally equivalent to tariffs. Whether such workarounds would survive judicial challenge under Learning Resources' background norm against finding tariff authority in vague statutory language is uncertain, but the attempt itself would generate a second generation of separation-of-powers litigation.

Each scenario raises distinct institutional questions. In the first, the question is whether Congress can design a tariff delegation that is specific enough to satisfy the major questions doctrine (at least as the plurality understands it) without being so rigid as to deprive the President of the flexibility he needs to negotiate trade agreements. In the second, the question is whether the political costs of legislative inaction — the disruption, the uncertainty, the retaliatory dynamics — will eventually force a legislative response. In the third, the question is whether the alternative statutory pathways can sustain tariff policies of the scope and magnitude the President has pursued, or whether those statutes' built-in constraints will prove functionally limiting in ways IEEPA's vague language was not. And in the fourth, the question is whether the Court's holding is robust enough to prevent circumvention — or whether it will join the long line of separation-of-powers rulings that constrain the form of executive action without ultimately constraining its substance.

F. The Remedy Question

The Court's opinion is self-executing in the sense that it declares IEEPA tariffs unauthorized, but it does not specify the remedy. This omission raises several questions that will generate further litigation. Are the tariffs void ab initio — never legally valid — or merely voidable from the date of the ruling? The distinction matters enormously for importers: if the tariffs were void from inception, then every dollar collected was collected without legal authority[93] and is owed back with interest. If they are voidable only prospectively, then the refund obligation may be more limited. The Court's holding — that IEEPA "does not authorize" tariffs — most naturally reads as a declaration that the tariffs were never authorized, but the opinion does not expressly address retroactivity. There is also a reliance interest question: businesses that restructured supply chains, renegotiated contracts, and made capital investments in reliance on the tariff regime may argue that sudden reversal imposes costs that the Court's remedy should address. And the Government may argue that immediate unwinding of all tariffs would cause as much economic disruption as imposing them did — an argument that has no doctrinal basis in the context of an ultra vires action but may carry practical weight in the remedial proceedings before the Court of International Trade.

G. The Compliance Problem