The $7 Associate: How Midpage.ai Drafted a Multi-Thousand Dollar Memo on immunity issues in the ICE shootings

Midpage is an up and coming AI-first legal research platform. It just released from beta a "drafting" feature that purports to produce legal memos, briefs and other documents grounded in the ability to research and reason about actual cases. I've been following Midpage for a couple of years and seen it improve greatly. So I wanted to see how well Midpage could do on a real legal problem.

The short answer is that Midpage does extremely well compared to a young associate in drafting a legal memo. It portends a revolution in the production of legal analysis. For less than $10 in AI charges plus perhaps two hours of associate time superintending the AI and reviewing its work, it appears that you get work comparable to that which would take a very strong young associate at least eight hours to complete. AI thus reduces the time needed for much legal work by over 75%. It makes quality legal work potentially available to a broader class of clients and changes the skill sets most needed by young attorneys. Clients should and I expect will start asking firms: "Why aren't you using platforms like midpage to reduce the cost of legal work?"

Here's the experiment I conducted. I've been interested in legal issues arising out of the ICE shootings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti in Minnesota, in particular what immunities the ICE agents have and impediments Minnesota might face should they indict and then seek to extradite the charged agent from wherever they might now be found. (There are also really interesting issues about what happens when Minnesota indicts and the state in which the agents now live resists extradition). I did some initial work with non-specialized AIs such as ChatGPT and Gemini. They were quite helpful in framing issues and identifying certain key cases. But in the end, those AIs left me somewhat unsatisfied. Their answers were OK, but they weren't specific enough; n light of the recency of the events they were addressing, I also worried about their particular vulnerability to hallucination.

The frontier general purpose AIs, however, did make a claim I wanted to explore further. It was the following.

And so, aware of Midpage's recent release from beta of its drafting feature, I thought this could be a twofer. First, I could learn about something important as justice is sought for what to many looks like an unjustified homicide by federal agents, and one that threatens first amendment, second amendment and other constitutional values. Second, I could explore just how far Midpage developers had gotten in their efforts to turn their search and chat AI-first legal research agent into a full blown partner in the production of legal materials.

I posed the assertion from frontier AI to Midpage and asked it to assess. I put shamefully little effort into my prompt. "Evaluate this assertion in the context of an ICE officer shooting an American citizen alleged to have been obstructing ICE operations." (I then inserted the claim above).

Midpage began by creating and then revising an organizational structure:

Research qualified immunity doctrine and standards (research + draft as found)

Research cases comparing/contrasting the two immunities (research + draft as found)

Research federal officer immunity in shooting cases specifically (research + draft as found)

It pursued those tasks in parallel and found 11 relevant cases. It then realized it needed to "research cases specifically involving ICE officers or federal officers in shooting cases to see how these immunities apply in that context, then evaluate the specific assertion." It found an additional six cases that it thought relevant. Midpage continued to iterate. Here is part of its internal monologue:

State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 215 F.3d 986 (9th Cir. 2000)

State of New York v. Jude Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004)

Texas v. Kleinert, 143 F. Supp. 3d 551 (W.D. Tex. 2015)

State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 253 F.3d 359 (9th Cir. 2001)

State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 253 F.3d 359 (9th Cir. 2001)

Arizona v. Files, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 104703 (D. Ariz. 2014)

United States v. Dodd, No. 1:08-cr-10100 (W.D. Tenn. Jan 6, 2009)

State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 215 F.3d 986 (9th Cir. 2000)

State of New York v. Jude Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004)

Texas v. Kleinert, 143 F. Supp. 3d 551 (W.D. Tex. 2015)

Edited content

Added two new sections to the draft: Section I.D discussing successful application of Supremacy Clause immunity in deadly force cases involving Horiuchi (Ruby Ridge FBI shooting), Tanella (DEA agent shooting), and Kleinert (federal task force shooting), and Section I.E explaining limits on immunity through Horiuchi II (immunity not absolute), Files (personal animus defeats immunity), and Dodd (pattern of misconduct exceeds scope).

What I like is that midpage.ai, like a good human legal researcher, is adapting to its findings. It is also seeking not to resolve the issue in the abstract but to try to find factual scenarios analogous to those posed by the Minnesota ICE shootings.

Midpage went through three internal drafts (which the Midpage user can see if interested), and spent about 10 minutes and about $3.50 worth of tokens on calls to OpenAI and similar large language model providers. The developers at Midpage were smart. They did not attempt to build their own frontier model. Rather they figured out how to piggyback on the efforts of those with expertise: Claude, OpenAI, etc. And they would charge customers a la carte for the tokens used, plus what they say is a small markup. (Even with the law professor $10/month plan, you still get $25 worth of free drafting tokens before you have to start actually paying by the token).

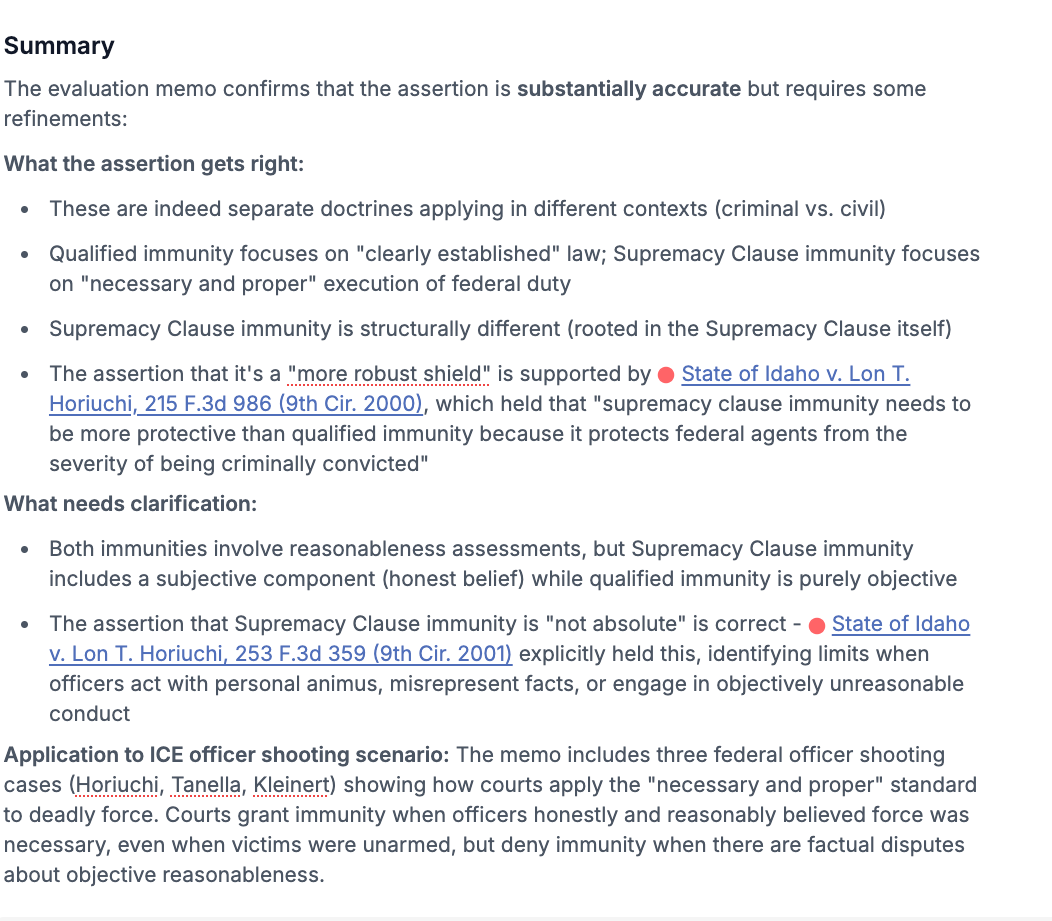

Midpage first returned an executive summary of what it had found and responded to the specific question I posed.

In a real-world legal setting, I would find identification of the key cases and the overall findings quite useful. But that is hardly all that Midpage produced. Additionally, it created a 4,000-word legal memo that had the look and feel of human lawyer work. The appendix contains a downloadable link. My quick reading of the work suggested quality. But was it really any good? In a perfect world of infinite time, I would carefully review the draft over hours, track down the cases cited, look to see if there were omitted precedents, and evaluate the argument thoroughly. But infinite time is not the world I inhabit. Instead, I fed Midpage's draft into Claude (not telling Claude that the output was from an AI) and asked it for an evaluation. In addition to resolving practical impediments, AI evaluation might in fact notice things that I would not.

Claude was generally enthusiastic about Midpage's efforts. Not informed of the non-human author of the memo, Claude estimated that it must have taken the associate 6 to 8 hours to produce. Claude praised the memo as very strong work product that substantially exceeds typical second-year associate quality, highlighting the associate's sophisticated legal analysis, excellent research skills (including comprehensive case law coverage across multiple circuits), and outstanding ability to synthesize complex immunity doctrines without conflating them. Indeed, it suspected that the associate must have used AI to produce 15 pages of polished prose and/or be in the top 5% of young associates. The feedback particularly commended the clear organization, precise application to the fact pattern (especially shooting scenarios), professional writing, and sharp understanding of why Supremacy Clause immunity is more protective than qualified immunity.

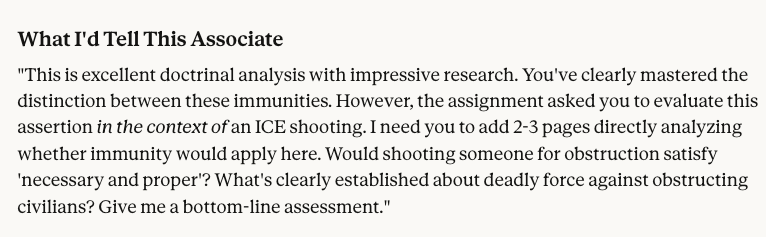

But Claude was not entirely satisfied. Claude flagged significant omissions, including the failure to directly apply the doctrines to the specific ICE obstruction shooting scenario, the absence of a tailored qualified immunity analysis addressing clearly established law or Graham factors in that context, and insufficient discussion of ICE-specific statutory authority under the INA that could affect the "scope of federal authority" element. Claude also critiqued the Midpage draft for lacking practical bottom-line conclusions on likely immunity outcomes, procedural implications, and for minor issues like repetition, overly long quotes, and missed opportunities to flag circuit splits or bolster assertions with footnotes.

Claude ended with feedback for the "associate."

Perfect! I could now give the critique and suggestions to Midpage and ask it for a second draft. Midpage began with a todo list.

It updated that todo list based on what it found and drafted a scenario-specific analysis addressing the partner's concerns about the ICE shooting scenario. Three more minutes, $4 more of API calls, and six further internal drafts later, Midpage had produced its output in the form of a 7,000-word, tightly organized, case-based Microsoft Word document.

Obviously, it doesn't make much sense to reprint the entire work in this blog entry, but I will provide a downloadable link in the Appendix and also provide the following excerpt.

D. Application to Federal Officer Shooting Cases

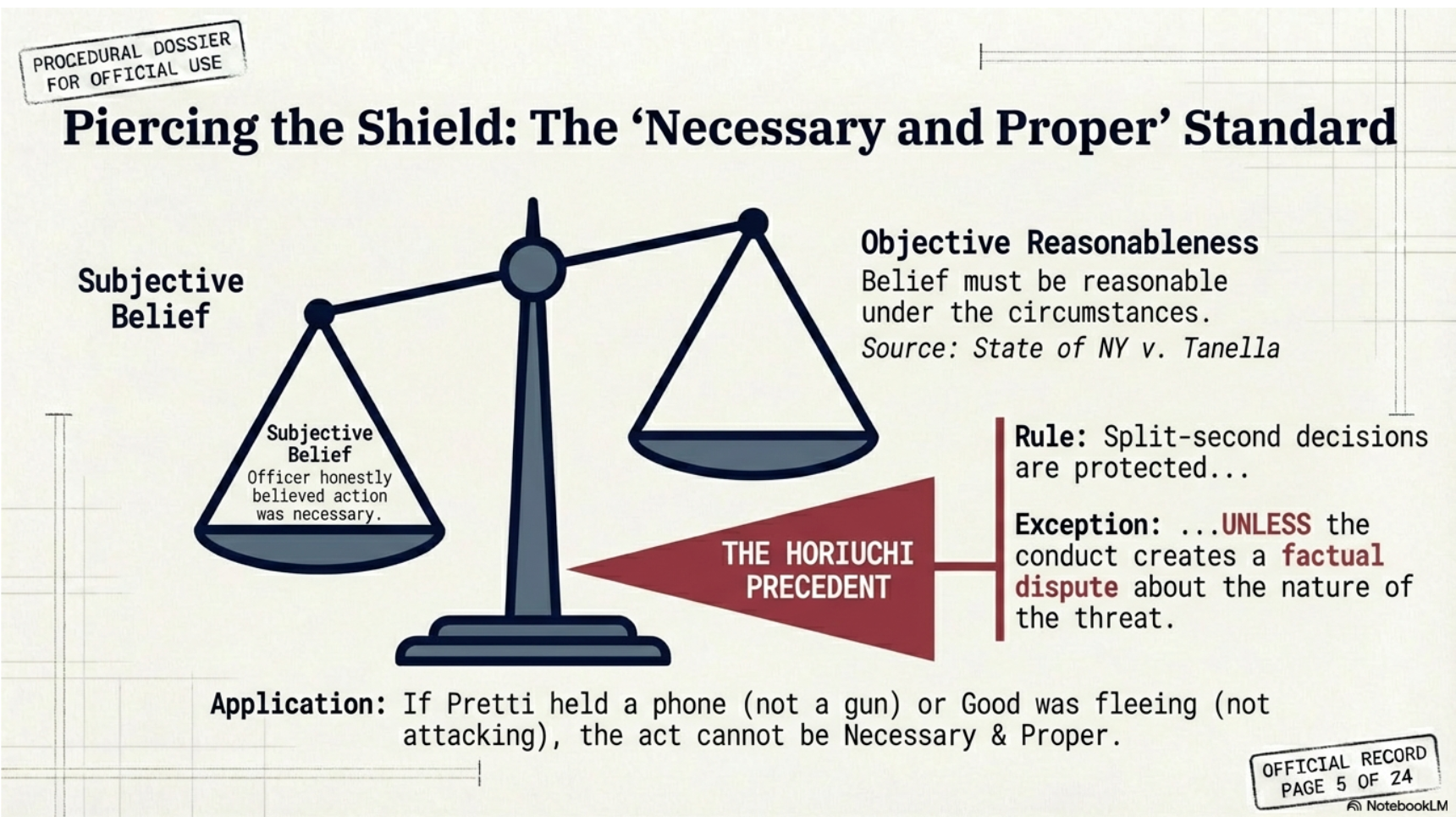

Federal courts have consistently applied Supremacy Clause immunity to dismiss state criminal charges against federal law enforcement officers who used deadly force while performing their duties. Three cases illustrate how courts analyze whether shootings were "necessary and proper" under the circumstances.

In State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 215 F.3d 986 (9th Cir. 2000), an FBI agent was charged with involuntary manslaughter for a shooting during the Ruby Ridge standoff. Agent Horiuchi had been briefed that a deputy U.S. Marshal had been killed, that the suspects were armed and dangerous, and that armed adults posed a threat. When Horiuchi saw an armed man running toward the cabin where he could take a defensive position and rearm, Horiuchi fired. The shot passed through the cabin door and killed Vicki Weaver, who was standing behind it holding a baby. The Ninth Circuit affirmed dismissal based on Supremacy Clause immunity. The court held that Horiuchi's belief was objectively reasonable because he "knew a federal officer had been shot; he knew that Harris was armed; he thought that Harris had threatened the helicopter; and he thought that Harris would present a greater threat to the agents if he reached the safety of the house." State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi, 215 F.3d 986 (9th Cir. 2000). The court emphasized that officers must make "split-second decisions" and that courts should not "dissect the events which flashed before a police officer in a matter of seconds" with the benefit of hindsight.

State of New York v. Jude Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004) involved a DEA agent charged with manslaughter after shooting a drug dealer following a high-speed chase and violent struggle. During the foot chase, Agent Tanella displayed his badge, identified himself as a police officer, and ordered the suspect to stop. When the suspect stumbled, Tanella "jumped on top of him" and the two struggled between parked vehicles. During the struggle, Tanella fired one shot that killed the suspect, who turned out to be unarmed. The Second Circuit affirmed dismissal, holding that Tanella's perception that the suspect was reaching for his gun was "objectively reasonable as a matter of law" given the "tense and perilous circumstances." State of New York v. Jude Tanella, 374 F.3d 141 (2d Cir. 2004). The court emphasized that Tanella knew the suspect was "a seasoned drug dealer" who had "demonstrated his criminal tenacity" through reckless driving and choosing to fight rather than submit to arrest. The court concluded that even eyewitness testimony suggesting the suspect was trying to flee rather than reach for a weapon was insufficient to defeat immunity because the reasonableness inquiry focuses on the circumstances "as they appeared to" the officer at the time.

Texas v. Kleinert, 143 F. Supp. 3d 551 (W.D. Tex. 2015) involved a federal task force officer charged with manslaughter after his firearm discharged during a struggle with a fleeing bank robbery suspect. Officer Kleinert, a deputized FBI agent and U.S. Marshal assigned to a federal task force, pursued the suspect on foot after witnessing federal offenses at a bank. When the suspect failed to comply with orders to stop and get down, Kleinert went "hands on" while holding his firearm, and during the struggle the gun discharged, killing the unarmed suspect. The district court granted dismissal based on Supremacy Clause immunity. Applying the Graham v. Connor factors, the court found that Kleinert's belief that he needed to go "hands on" with his firearm drawn was objectively reasonable given the suspect's noncompliance and flight. Texas v. Kleinert, 143 F. Supp. 3d 551 (W.D. Tex. 2015). The court emphasized that federal task force training materials contained "no prohibitions" against going "hands on" with a firearm when dealing with noncompliant suspects, and that "sometimes it happens and is necessary." Critically, the court noted it need "not decide that Kleinert correctly evaluated the situation, but only that he honestly and reasonably perceived the situation."

These cases establish that Supremacy Clause immunity applies even when federal officers shoot unarmed individuals, provided the officer's belief that force was necessary was objectively reasonable from the perspective of a reasonable officer facing the same circumstances. Courts consistently emphasize that the analysis must account for the "split-second" nature of use-of-force decisions and avoid the "temptation" to second-guess officers with the benefit of hindsight.

Perhaps I am insufficiently picky or my enthusiasm betrays that I have never been a biglaw partner, but I would rate this sort of analysis as first rate. It reads very much like a traditional legal memo, has clickable links to real cases, and produces information that a law firm getting involved in the case would find useful.

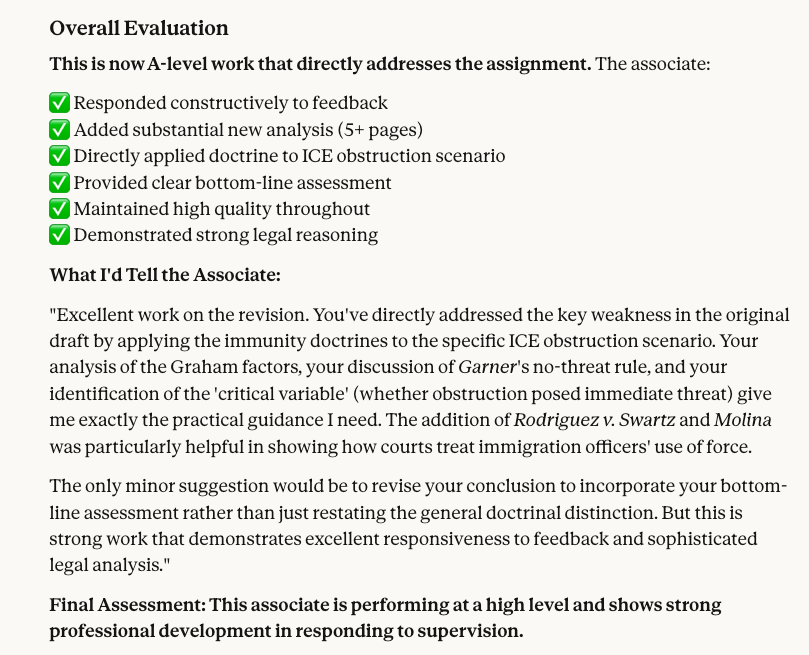

I also asked Claude how it felt about the final product. Here's a summary.

Using Midpage Drafts in Conjunction with Other Skills

I won't dwell on this here, but the open nature of Midpage's work means that it is easy to harness other AIs to produce derivative works. Set forth in the Appendix, for example, is an "eardraft" summary of the memo, explaining for journalists and others what the memo says in a way that is better suited to the spoken word. You can, as I have, stuff the resulting memo into NotebookLM along with other material related to the event and ask it to produce a slide deck describing the issues for law students (see sample slide below) or one of its classic podcasts doing the same. In short, the Midpage output becomes grounded input that other AIs can rely on.

Critique

Have I really "proven" that Midpage produces output at least as good as that produced by most young associates and at a fraction of the cost? No. I have not rigorously analyzed the response of Midpage. I have not undertaken to sample how some group of junior associates would perform on a similar assignment. And if that's the standard of proof you demand before experimenting with AI for the production of legal materials, you are likely to be dissatisfied with this blog entry. But given the immense challenges of conducting a large scale and rigorous experiment of the sort that would produce something resembling a proof, that degree of rigor might cost you the serious consequences of a false negative. To me, it is pretty darned obvious that these AIs are today capable of producing something quite good much more cheaply than that of most human lawyers who would otherwise do the work. I suspect that many law firm clients will feel likewise.

The more difficult critique is that AI may still not be good enough to produce documents without extensive human supervision and checking. At the beginning of this blog entry, I suggested that the human component of production would be less than two hours, perhaps 30 minutes of babysitting the AI through the initial prompt and an iteration and perhaps an hour or two checking the work product. Perhaps, however, those are underestimates. If one is genuinely mistrustful of AI because of the small chance that even grounded AI can mess up or because of its occasional failure to see the big picture or think creatively, checking its work may still require hours of work. Yes, the associate is spared the actual drafting, but a thorough review of AI-produced work will still take time. There is also the matter of the $99 per month law firms have to pay for a Midpage subscription. (Law professors and students get it for an addicting $10!) Most firms, I suspect, are clever enough to pass on this cost or simply to absorb it as a minor cost of doing business in the modern world.

A Rebuttal

There is something to these critiques, but I do not find them devastating. As others have observed, what AI does is turn associates into partners. It should give younger lawyers the same role that senior lawyers have now: to look at the big picture, to challenge contentions that seem implausible, to spot check work to reduce the probability of gross procedural errors by the person doing the drafting, to look for overstatement and loss of nuance, to consider issues of personality and institutions of which the more junior lawyer is unaware. Thus, even if it takes more time than I have budgeted to review the work of the AI, I very much doubt it will approach the amount of time it would have taken the human lawyer to do the work in the first place. A reduction in legal costs of "only" 50% would still represent a profound change in access to justice.

Moreover, any deficiency in Midpage's performance as of January of 2026 is not really the issue. First, with all respect to Midpage, it has no moat. Midpage is basically using a legal database and using intelligent workflows to orchestrate very clever prompts sent to frontier AI. The people there are very smart, are doing an outstanding job, and have embraced a high degree of openness – for example, they plan to permit direct integration with Claude in the near future. But there are other entities with legal databases and still more with the power to purchase them should they be motivated to do so. Lexis and Westlaw are making tentative steps in this direction, but imagine what the world looks like when Alphabet/Google with a $4 trillion market cap creates the equivalent of its AntiGravity coding agent or AIStudio for the vast universe of legal data or that which it can acquire for rounding error of its budget.

I'm not even sure it takes a mega-company such as Google to cross the Midpage moat. Collaborations between smart lawyers and smart AI professionals can generate AI prompts and workflows that largely replicate Midpage's efforts. Indeed, a good use of AI would be to evolve workflows that autonomously improved the process. (Maybe Midpage's success is in part due to such an evolutionary algorithm?) All you need is a good reward function. In the meantime, I would hardly be surprised if some larger AI or LegalTech company got a head start by making a move to buy out Midpage or its trade secrets for a large sum in the same way that Clio recently bought out vLex for $1 billion.

Midpage's success in legal drafting should be seen as the analog to the much larger coding world of agentic AI that is exploding as we speak. Claude Code, Anthropic's agentic coding tool, lives in a developer's terminal or gets wrapped in a GUI, understands an entire codebase, and executes tasks autonomously—editing files, running commands, creating commits, iterating on work until it succeeds. A senior Google engineer reportedly used it to recreate a year's worth of programming work in an hour. Its architecture means that that plugins such as Superpowers or the more recent "Ralph Wiggum loop" can extend the inherent powers of Claude Code even further. And when Anthropic noticed that developers were using Claude Code for non-coding tasks—vacation research, slide decks, organizing files—they built "Cowork" in about a week and a half, largely using Claude Code itself to do the work. Cowork, which lawyers can and should use, gives Claude access to a folder on your computer and lets it read, create, and edit files autonomously to accomplish tasks like reorganizing downloads, creating expense spreadsheets from receipts, or compiling research reports from scattered notes. And, yes, yes, there are issues of confidentiality but these should be solvable with careful granting of permissions.

I'm sorry but there isn't really much "law exceptionalism." Doing high quality coding by integrating megabytes of existing code bases isn't all that different than doing high quality legal drafting by integrating megabytes of existing legal materials, particularly when AI has already extracted structured data from the raw text. Imagine "Claude Associate" or "Google Associate" putting beautiful user interfaces around API calls that can access diverse amounts of legal materials, reason about them with modest human intervention, iterate, refine, self-critique, and draft. Imagine MCPs (or their successors) being available to make the process even easier for people. It is going to be as extraordinarily hard for human lawyers to compete as it is now for human coders to compete. Given the exponential growth of AI capabilities and scaffolding, I don't think we will have to wait long.The key human skill – for at least a few years until it too is ultimately displaced – is going to be learn how to harness these vibe drafting agents effectively.

As I hope this blog entry suggests, the drafts of Midpage today look very, very promising. In the world of legal education, every professor, every administrator, every legal writing instructor, every law student needs to take a hard look. Midpage's success exposes that AI should no longer been seen as merely a research assistant but a competent architect of legal prose, capable of grounding complex arguments in authentic case law. As a starter, the traditional "closed-universe" writing assignment, designed to test a student's ability to synthesize a discrete set of precedents, is rapidly becoming obsolete when agentic systems can perform the same task with greater speed and comparable precision. To remain relevant, law schools must shift their pedagogical focus from the mechanics of initial drafting to the high-level cognitive skills of "AI superintendence"—teaching students how to rigorously edit and audit machine-generated outputs for nuance, ethical compliance, and strategic alignment. Rather than banning these tools, faculty must integrate them into the curriculum, ensuring that the next generation of attorneys is defined not by their ability to out-draft the machine, but by their capacity to masterfully direct and refine its power.

Before you scoff or say that this years in the future, I would like you to actually read that final draft memo produced by Midpage. I think you will be quite impressed. Recognize, however, what you see there is just the floor on AI performance. It is the equivalent of ChatGPT version 2. Today, Midpage may be better than 95% of young associates at 1/4 the price. I would not be shocked if, in light of that math, by no later than this time next year many clients were simply demanding that firms use AI for drafting.

Appendix

Link to the initial draft from Midpage

Link to the revised draft from Midpage.

An "Eardraft" summary of the legal memo produced by Midpage.