Legal professionals should use AI to create spreadsheet models

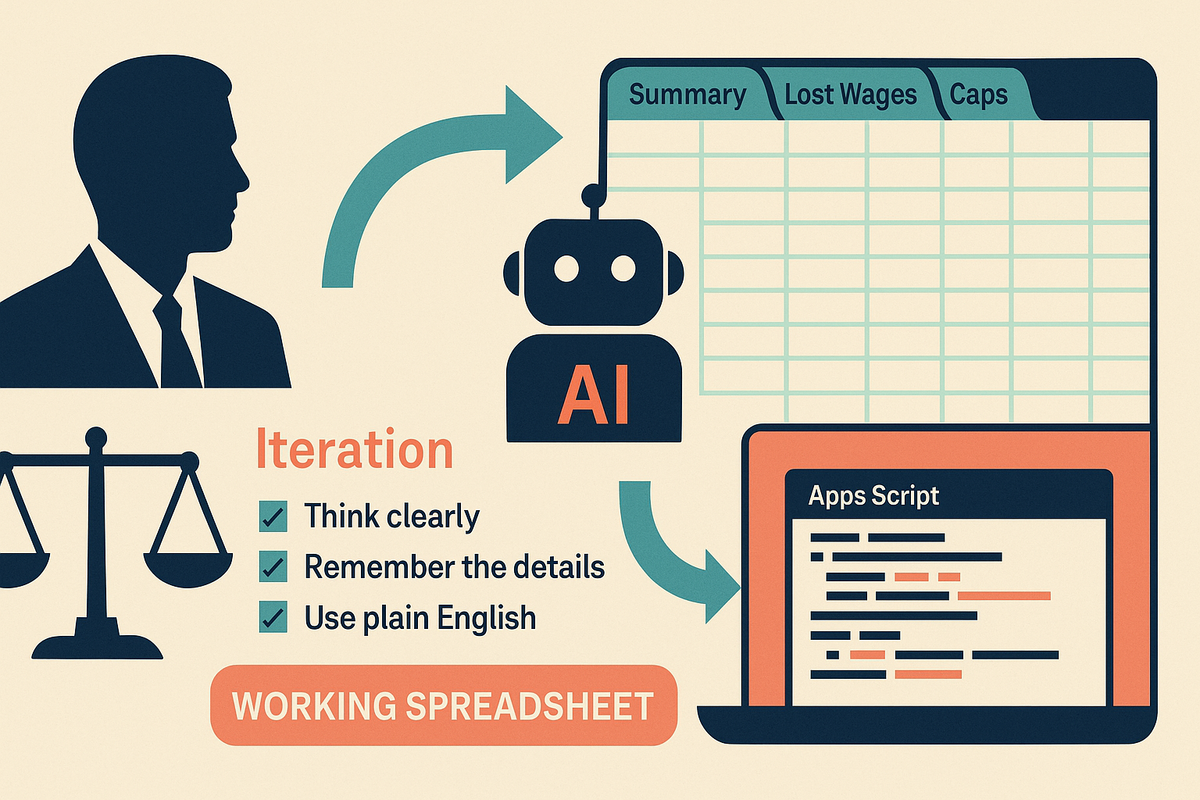

With today’s tools, legal professionals can build real software. And, for reasons we will discuss, they should. You don’t have to learn a programming language anymore. You don't have to memorize syntax. You do what lawyers tend to do well. Think clearly, remember the details, use plain English, and not panic when things go wrong, which they will in programming as much as they do in lawyering. You do so to recruit AI as a partner. You provide the ideas and troubleshoot. It creates a working spreadsheet for you.

This is the first in a playlist of blog posts on coding for legal professionals. In this one, I want to show you how to use AI to create a spreadsheet, first in Excel then in Google Sheets. Some of this I covered in a prior blog post, but we will get more into the process here. My hope is that this explanation will whet your appetite for later posts in which we do more sophisticated programs. The skills learned here: speaking clearly, examining the results carefully, iterating, and – perhaps above all – not panicking when things inevitably go wrong, definitely transfer over when more sophisticated programming endeavors are attempted.

Why Excel?

Excel is an underrated on-ramp to programming for legal professionals be they students, faculty or practitioners. It’s ubiquitous in firms and courts, most lawyers already know how to navigate cells and filters, and it offers immediate visual feedback—tables, pivots, and charts—that make logic tangible. Historically the barrier was wrestling with relative vs. absolute references and hunting for the right formulas, but with AI you can describe the outcome (“flag filings more than 60 days after service, exclude weekends and federal holidays, and color late rows red”), get the exact formula or Power Query steps, and paste them in without memorizing syntax. The result is real computation—validated calculations, reproducible workflows, and shareable dashboards—achieved through plain-English prompts and small checks (named ranges, sample test rows, a notes tab explaining assumptions) that let lawyers focus on capability rather than minutiae.

The Damages Calculator

A very simple model

Let's start by building a simple damages calculation model for a personal injury case. Here was all the code I provided Claude Desktop. I picked Claude Desktop because it has by far the smoothest integration right now with Excel and, frankly, because I wanted to play around with its new Sonnet 4.5 model, which appears pretty spectacular to me and others. (I do pay about $20/month for Claude which gets me access to the Desktop app).

"Build an Excel damages calculation model for lawyers in a personal injury case. Start simple."

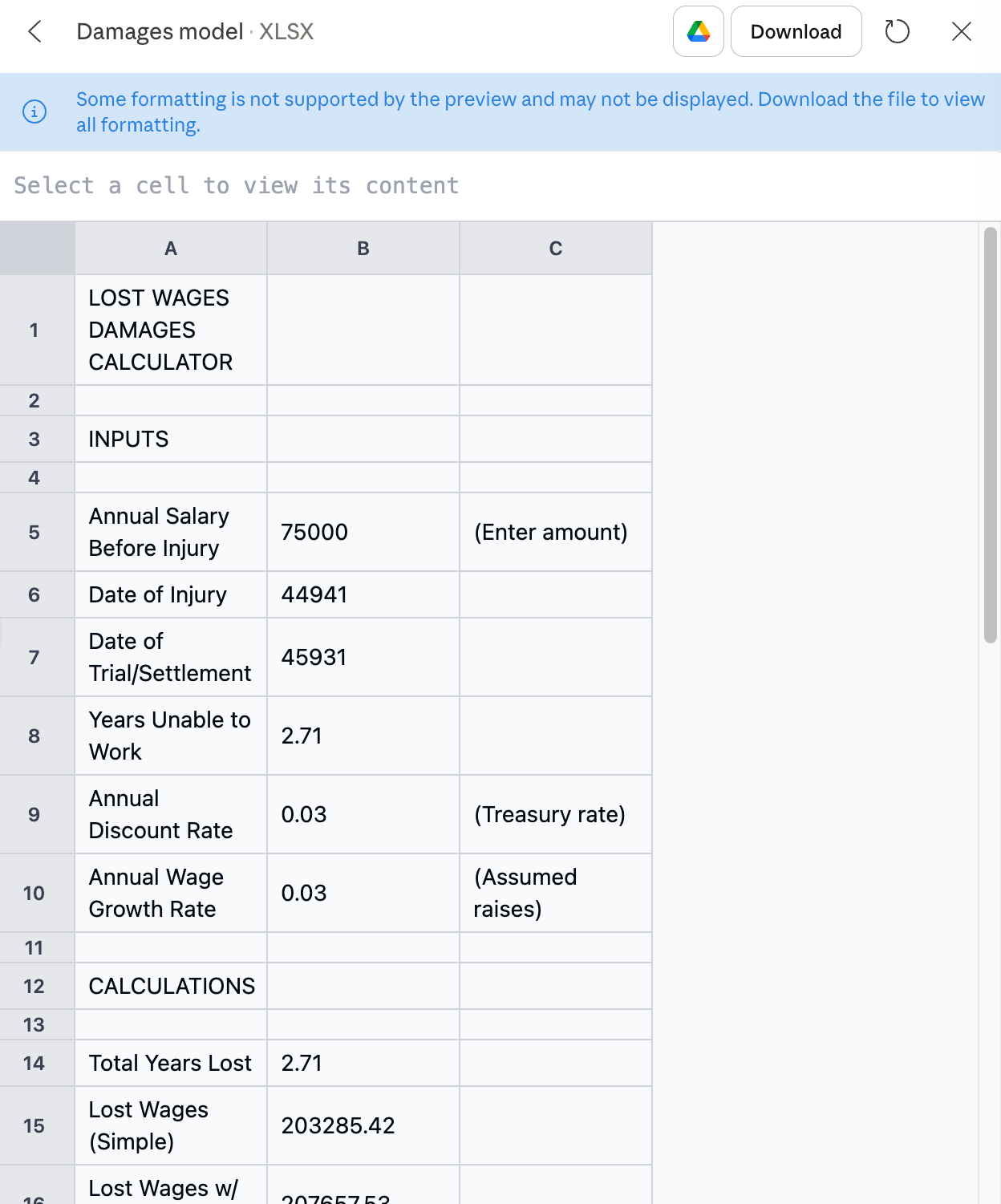

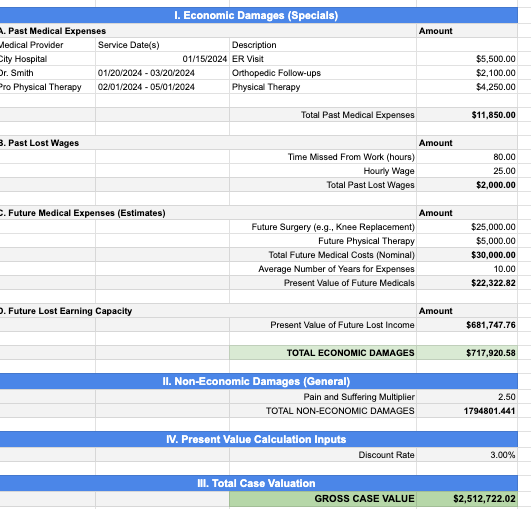

Claude does so in a minute or two and provides the following preview.

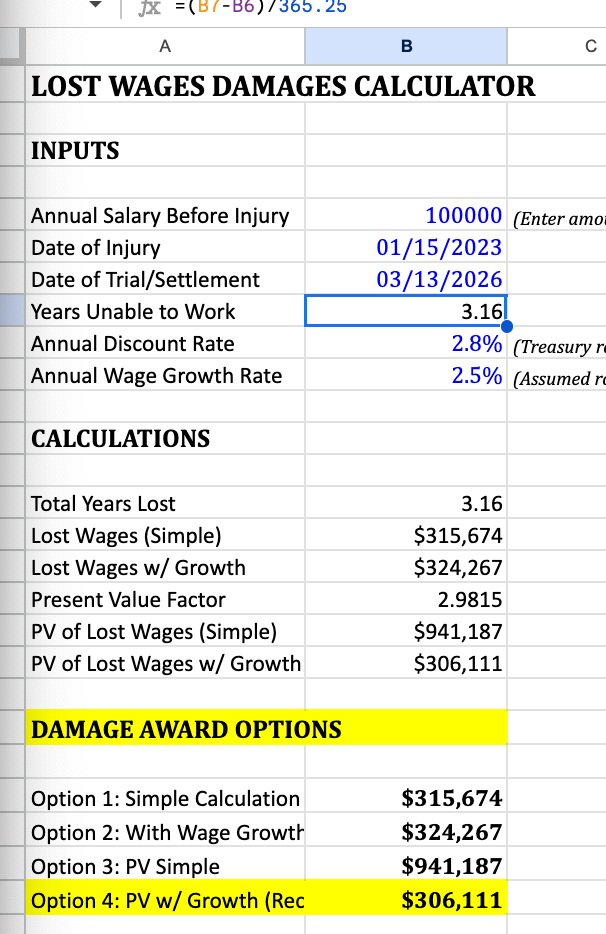

I then press on the Google Drive button (the multicolor rounded triangle) and I get a working model that I can manipulate. For example, I can change the annual salary before input to $100,000, change the date of trial or settlement to 3/13/2026, and change the discount rate to 2.8%. Here is the new result:

A multi-tab model

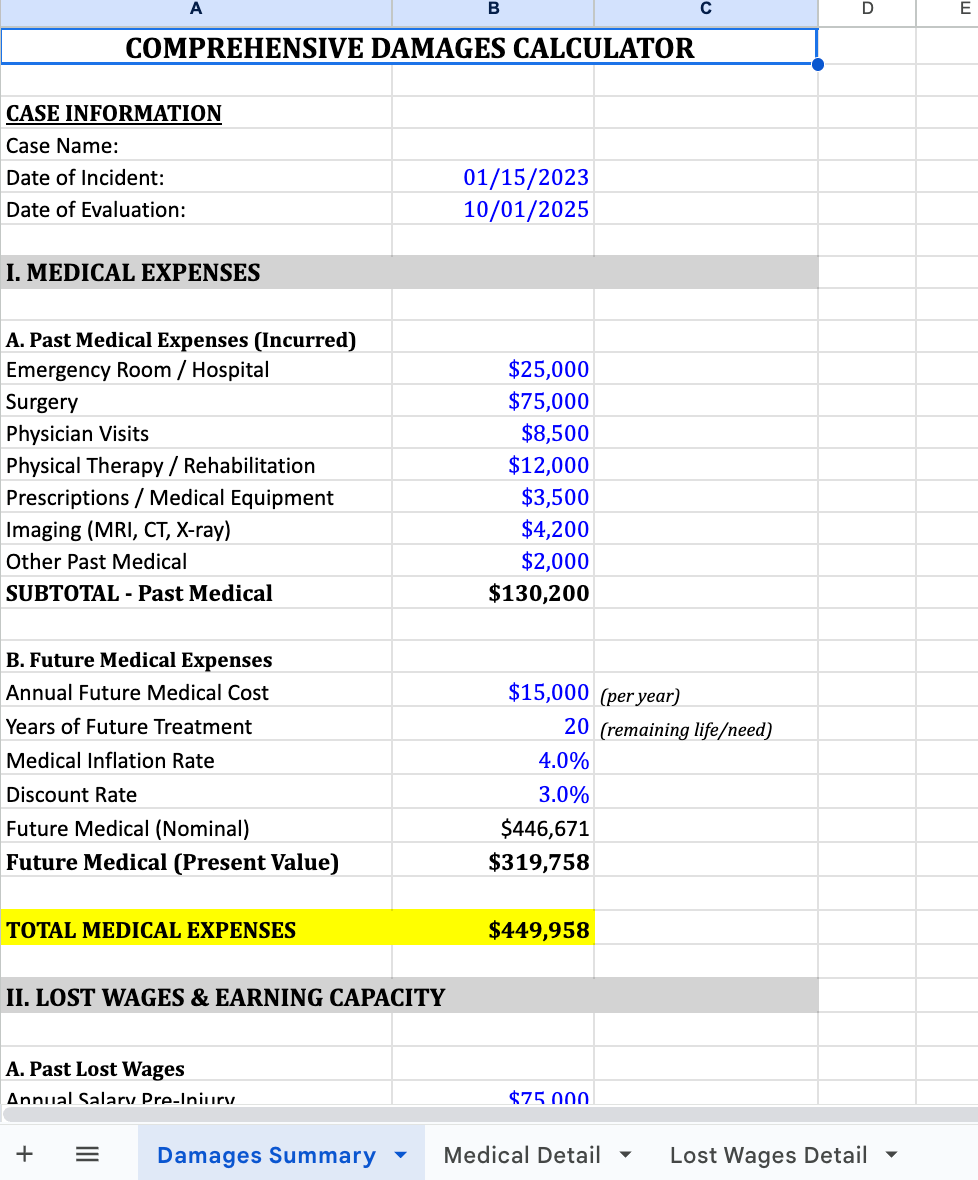

But that isn't a very sophisticated calculator. I asked the AI what we would need for a more sophisticated model and then asked to build it. Again, AI obliged with a calculator that includes medical expenses, tax adjustments, other economic loss and non-economic damages. We end up with a three-tab spreadsheet shown below.

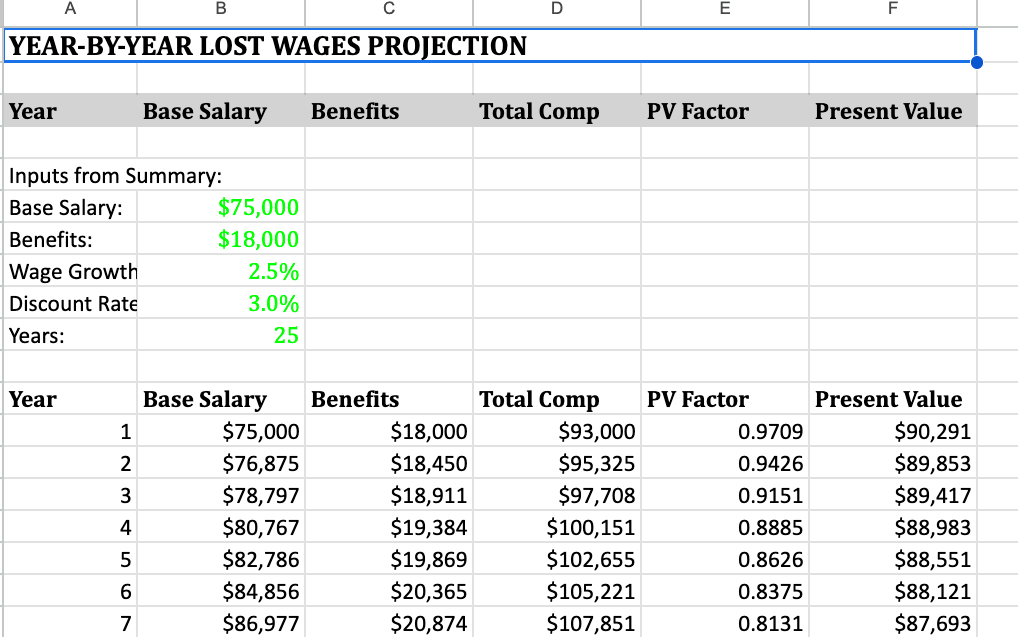

The detail tabs permit adjustments to matters such as benefits and working lifetime of the individual

Adding Damage Caps

The spreadsheet is not perfect. The lawyer in me recognizes that non-economic damages are capped in many states. The spreadsheet really needs to take that into account. Also, when I use the spreadsheet I notice a lack of synchronization between user-changeable values such as years of work lost in different tabs. This provokes the following prompt.

You observe correctly that non-economic damages may have caps in some jurisdictions. Is there a way you could do some legal research into caps existing in various states, including Texas, and figure out how to parameterize them. Then tell me how you would include that parameterization in a revised Excel sheet. Don't do it yet. Also, I noticed that on the lost wages detail tab, the table does not truncate or expand rows depending on the years. It does not affect the bottom line, but the table is not right. Also, shouldn't the inputs in the damages summary screen sync with those in the lost wages detail sheet. I am not sure which should be primary but you should not be allowed to have two different values.

After acknowledging the problem and doing corrective research, Claude Desktop comes back with a proposed solution. I accept the solution and the AI creates an improved spreadsheet. You can play with it here. Notice that I am not writing any Excel code here. I am just using my skills as a lawyer to both specify with clarity what I want and to ensure the model, even if mathematically correct, conforms to the legal environment in which it will be used.

Google Sheets

Excel is an excellent and time tested environment. But it is not the only one. Google Sheets has the advantage of being truly free – good if your client is poor – and running on numerous platforms including iPhones and Android phones. It's also easier to share your work with Google Sheets than with Excel. Unfortunately, creating a Google Sheet is, as of early October 2025, not as straightforward as creating an Excel sheet in Claude Desktop. However, it is still quite doable for someone without technical skill.

We can use several alternative LLMs to create the program that builds the Google Sheet. Let's use Gemini, which, as a Google product, perhaps knows something about Google Sheets. Most of it is easy, except as is too often the case, getting the needed permissions to create a document stored on a server like Google Drive.

Here is the prompt you need to create a script that builds the Google Sheet.

Build an Google Sheets damages calculation model for lawyers in a personal injury case. Start simple.

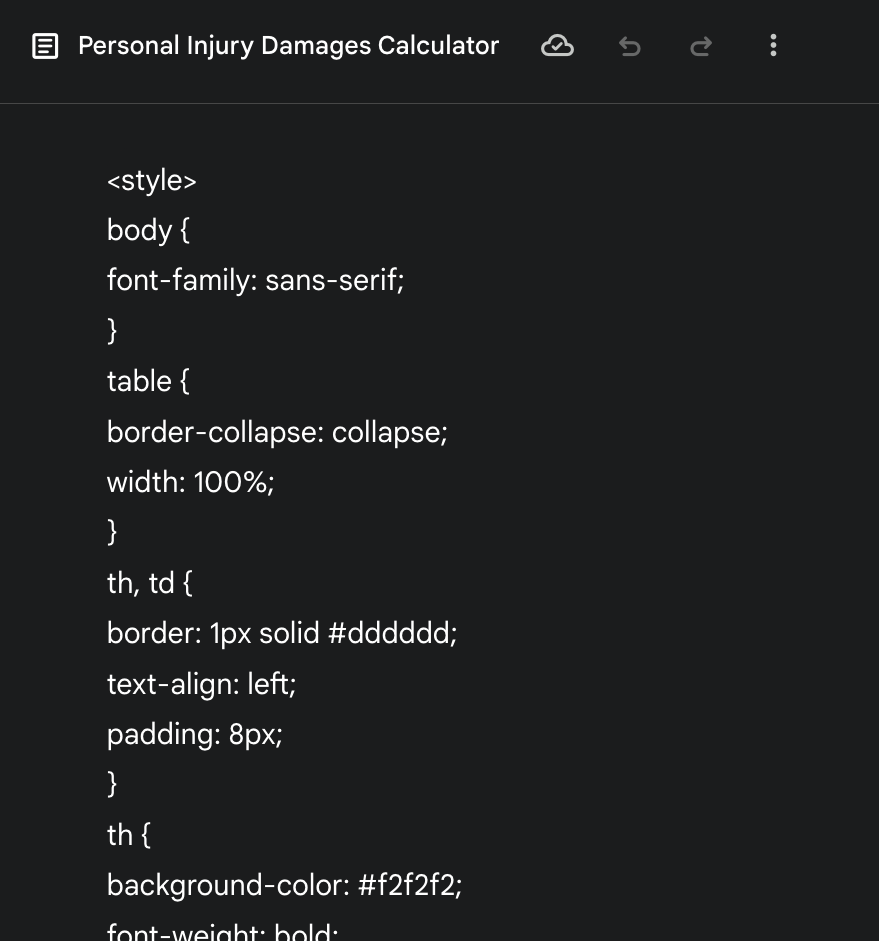

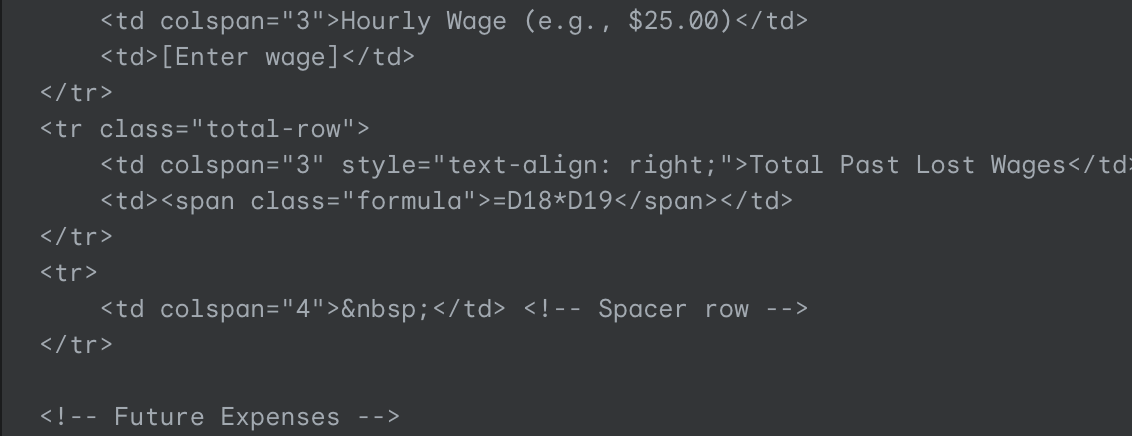

The result is a Canvas that contains some HTML code. It starts off with some styling information.

Here's some additional code showing the development of needed formulae.

Sadly, although Gemini lets you read from existing Google Drive documents, it does not let you create them or modify them. Gemini does not have an "Open in Google Sheets" button to let you move directly from code to a Google Sheet. Instead, you have to follow this recipe. Conceptually, what you are doing is giving Google Sheets an "Apps Script" (a/k/a a program) from which Google will actually construct the sheet that you thereafter use. Everything should be easy until you get to the treacherous matter of permissions. Come on Google – fix this!

- Open a new, blank Google Sheet.

- At the top, click on Extensions -> Apps Script. A new tab will open with the script editor.

- Delete any placeholder code that is in the editor window (e.g.,

function myFunction() { ... }). - Copy the entire script from the file below and paste it into the empty script editor.

- Click the Save project icon (it looks like a floppy disk).

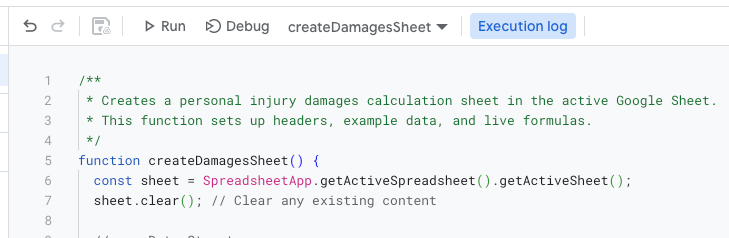

The top of your script tab should now look something like this:

- At the top of the script editor, make sure the function

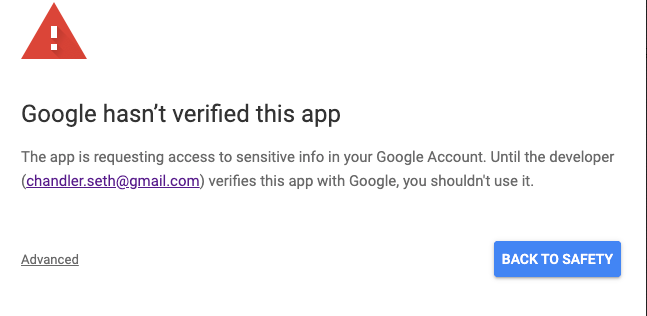

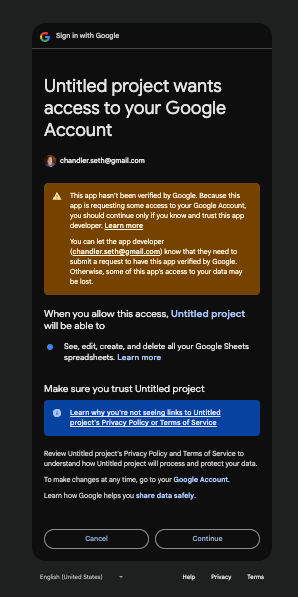

createDamagesSheetis selected in the dropdown menu, then click the Run button. And here is where a tricky issue arises. You will likely see a box pop up saying "Authorization required" with a blue "Review permissions" button. Basically, Google Sheets doesn't want rogue code injected. You will then be asked to sign in with Google using a Google account. Select the account. You will then see this scary screen.

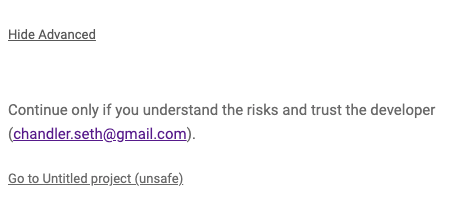

Do not fear. You are the one creating the app so instead of pressing the comforting "BACK TO SAFETY", take a risk and click on "Advanced." You will then see something like this:

You then do the thing that seems so counterintuitive. Don't press on your email address. Instead, you press on the link that says "Go to Untitled project (unsafe)." You then get yet another scary warning.

Forge ahead. You, after all, are the developer. You are unlikely to sabotage your own work, at least not as a result of using a trusted AI like Google Gemini.

Boldly click on the "Continue" button at the bottom. If all goes well you will then see the spreadsheet.

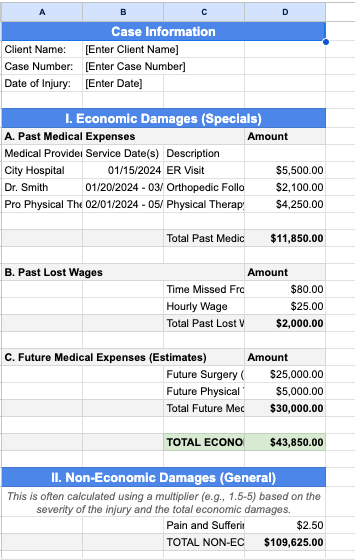

If all goes well, you should at last see a spreadsheet. It will look something like this.

It works but it is not attractive because the columns are too narrow. That can be easily fixed by hand within Google Sheets. Humans have learned to drag and drop very well over the decades. The other issue is that the loss model is really too simple. It contains, for example, information on past lost wages but nothing on future income loss. But now that we know how to get Apps Script code from Gemini to Google Sheets, remedying this deficiency shouldn't be too hard. And once we've created the permissions, we don't have to endure that rigamarole again. We just delete the old Apps Script, paste in the new script that Gemini creates, save, rerun and hope for the best.

I'm going to cheat a little bit and ask Gemini to read the Excel spreadsheet we created earlier in this blog. I am then going to ask Gemini to describe its capabilities. That way, I can get the functionality of the Google Sheet to closely resemble that of the Excel spreadsheet. Here is the result.

Automated Calculation & Structure:

Live Formulas: The sheet is built with pre-populated, active formulas. As you enter or change numbers for medical bills or lost wages, all the totals and the final case value update automatically.

Logical Organization: The document is clearly divided into three main sections:

Economic Damages: Tangible, calculable losses.

Non-Economic Damages: Intangible losses like pain and suffering.

Total Case Valuation: The final summary of all damages.

Detailed Breakdowns: Within Economic Damages, it has distinct sub-sections for Past Medical Expenses, Past Lost Wages, and estimated Future Medical Expenses.

User-Friendly Design:

Guided Entry: It includes placeholder text (e.g., [Enter Client Name]) and example entries to show you exactly what kind of information to enter and where.Lost Wages Calculator: You don't have to calculate lost wages separately; you can simply enter the hours missed and the hourly wage, and the sheet calculates the total for you.

Pain and Suffering Multiplier: It incorporates a standard multiplier method for calculating non-economic damages and includes a note explaining how it works. You can easily change the multiplier (e.g., from 2.5 to 3) to see different valuation scenarios.

Professional Formatting:

Clean Layout: The script automatically adjusts column widths, merges cells for headers, and aligns text for a clean, professional appearance.

Color Coding: It uses distinct background colors to highlight major section headers, total rows, and the final "Gross Case Value," making the sheet easy to read and navigate at a glance.

Currency Formatting: All monetary values are automatically formatted as US dollars (e.g., $5,500.00).Now I just ask Gemini to recreate the idea in Google Sheets.

Create a new Google Sheets document with the same capabilities as the one I just showed you. That one was created in Excel and uploaded to Google Drive. I want this one to be a native Google Sheet app.

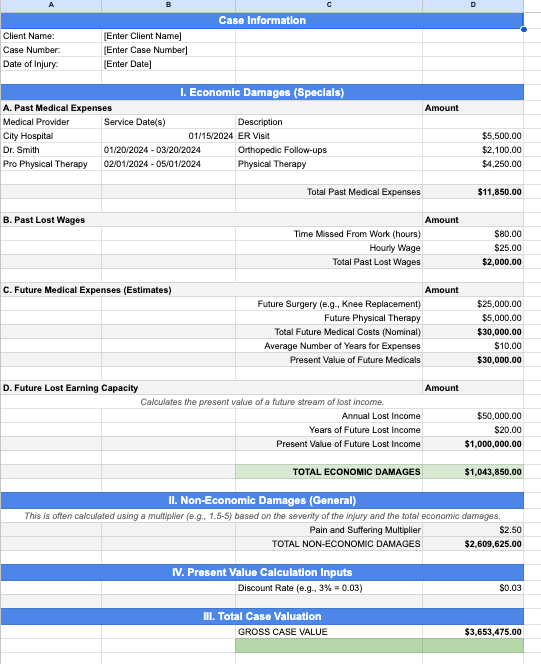

We go through the same recipe described earlier for moving a script between Gemini and Google Sheets, and then saving and running the script. The result is a revised spreadsheet that now looks like this.

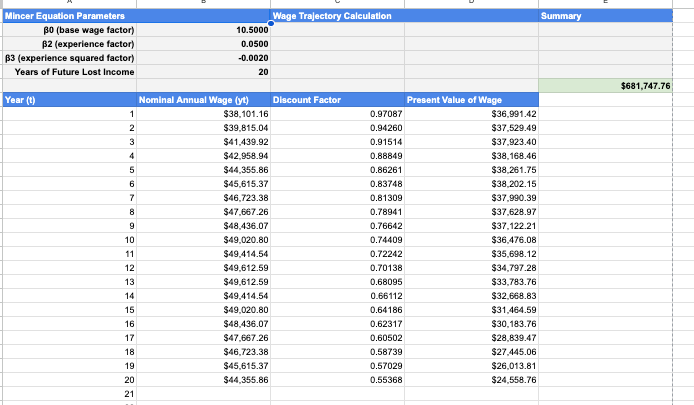

We're getting there. But the lawyer and math guy in me sees some issues. Here's the next prompt to Gemini. I do a little AI research and discover that a common way of creating a wage trajectory is to use a so-called Mincer model.

The formatting here is bad because various things like the discount rate are treated as currency. So too is years of future lost income. You need to use logic and go through each item and determine whether it should be formatted as currency. And the math is bad because you assume wages are flat. Create a second sheet in which the parameters are the number of years the person works in the future and the parameters needed to construct a Mincer wage trajectory: yt=exp(β0+β2t+β3t^2). Then take each value and discount it back to present value. The main spreadsheet should sync with the sum of the present values of the Mincer wage trajectory.

A Digression

This back-and-forth demonstrates a core concept in software development: iteration. We began with a script that functioned on a basic level but contained clear errors and lacked key features. Through successive refinements, we improved it.

The workflow for refinement here —repeatedly copying and pasting code into the Google Apps Script editor—introduces significant friction, however. This friction is compounded when the AI model requires several corrections to fully grasp the required details. While other approaches, like using Claude's desktop app with Excel, can mitigate some of this clumsiness, a far better solution exists. In a future article, I'll show how integrating AI into a true development environment like Visual Studio transforms this iterative process, making it substantially more efficient. I wish we could have used this technique with our Google Sheets project. Unfortunately, I can't find robust Visual Studio extensions that can interface directly with Google Sheets.

Back to business

After our last iteration, we have something reasonable. Here's the wage trajectory.

And here's the main damage calculator. You can play with it here.

Obviously, there's much more we could do with both the Excel and Google Sheets calculators: punitive damages, probabilities, subrogation and so much more. But the point here is not to build the ultimate personal injury lawyer calculator. It is to show how the average attorney without programming skills can now use AI to at least sketch out a working damages model that they can use to begin negotiations, provide to their own expert, or use to examine and potentially confront opposing counsel and witnesses.

What to do when things go wrong

I smoothed over a few rough edges in these projects because showing every little wart would be very tedious. And the details are unimportant. What is important is learning how to deal with errors. Fortunately, large language models have been trained on millions of error messages and often have a very good idea of what has gone wrong. What you need to do is copy the error messages either as text or as a screenshot (I love this program). Then paste it into the same LLM you have been using to program and provide with context as to when and how the error happened. "When I hit the "Run" button, I received this error message in the Execution log: 3:30:34 PMErrorTypeError: sheet.getXXXXXXXXRange is not a functioncreateMincerSheet@ Code.gs:169createNativeDamagesSheet@ Code.gs:87." Not always, but very often, the LLM will immediately diagnose the error and tell you how to fit it. If your LLM is blessed with an MCP server that connects with documentation about the programming tool, make sure to ask the LLM to use that tool to help with diagnosis. And if you don't understand the preceding sentence, just ignore it 😸

The why?

So far I focused on the "how" in this blog. I hope I persuaded you that in an era of AI you can indeed create relatively sophisticated spreadsheets with only a modicum of work. And those capabilities will only expand in the years ahead. But what I have not quite addressed yet is the why.

The answer isn't that every lawyer needs to become a software engineer—it's that understanding what's possible fundamentally changes how you practice law. When you can build a working damages calculator some slow afternoon, you gain leverage in settlement negotiations, cut months off case preparation, and deliver value for multiple clients that would have cost $15,000 from a consultant just five years ago. Plus a damage calculator just scratches the surface of what can be done in a modern spreadsheet. Modern spreadsheets can serve as flat databases holding thousands of rows of billing information, client information, case information, and much more. Writing custom programs that can read them in, manipulate them and produce other spreadsheets is a very useful skill.

For law teachers, there are, to be sure, research tasks in which a spreadsheet is extremely useful. Perhaps the most natural application of programming, however, might be in simulation-based courses—damages, negotiations, trusts and estates—where students currently work problems by hand or with calculators. Have the students build the tool first, then use it. A student who has built a lost wages calculator, debugged why it initially produced negative numbers for certain retirement ages, and figured out how to sync inputs across tabs has engaged more deeply with present value, mortality tables, and damage mitigation than one who simply plugged numbers into a form. The pedagogical value isn't the spreadsheet itself; it's forcing students to specify their assumptions precisely enough that a computer can execute them. That's harder than it sounds and reveals conceptual gaps that traditional problem sets miss. It will let them ask far better questions during depositions. It's also, frankly, more interesting than working the same hypothetical by hand for the fifteenth time. And, of course, to the extent that faculty or law students have administrative tasks – tracking assignments, tracking dozens of applicants for faculty positions through the multiple stages of that process – learning how to create and manipulate spreadsheets helps significantly with organization.

Finally, even if you ultimately hire experts to build sophisticated tools, your fluency with the process—knowing what questions to ask, what's trivial versus complex, what can be automated and what can't—prevents you from being overcharged or misled. You can evaluate vendor proposals critically, catch errors in expert models, and communicate precisely about what you need rather than accepting whatever off-the-shelf solution is pitched to you. In an era where litigation increasingly turns on data, predictive models, and computational analysis, lawyers who understand programming aren't just more efficient—they're better advocates. They can see solutions others miss, challenge analyses others accept blindly, and deliver results that astonish clients who are accustomed to paying premium rates for work that AI can now help produce in hours. The investment isn't learning to code—it's learning to think computationally, and as we go forward in an era of AI, may prove as fundamental to legal practice as knowing how to research case law.

Postscript: Generating Excel in ChatGPT

As it happens, an hour after I posted this blog entry, I learned from one of my students just how easy it is to create an Excel file in ChatGPT. These kids today!

Here's the prompt I used to generate a personal injury damages calculator.

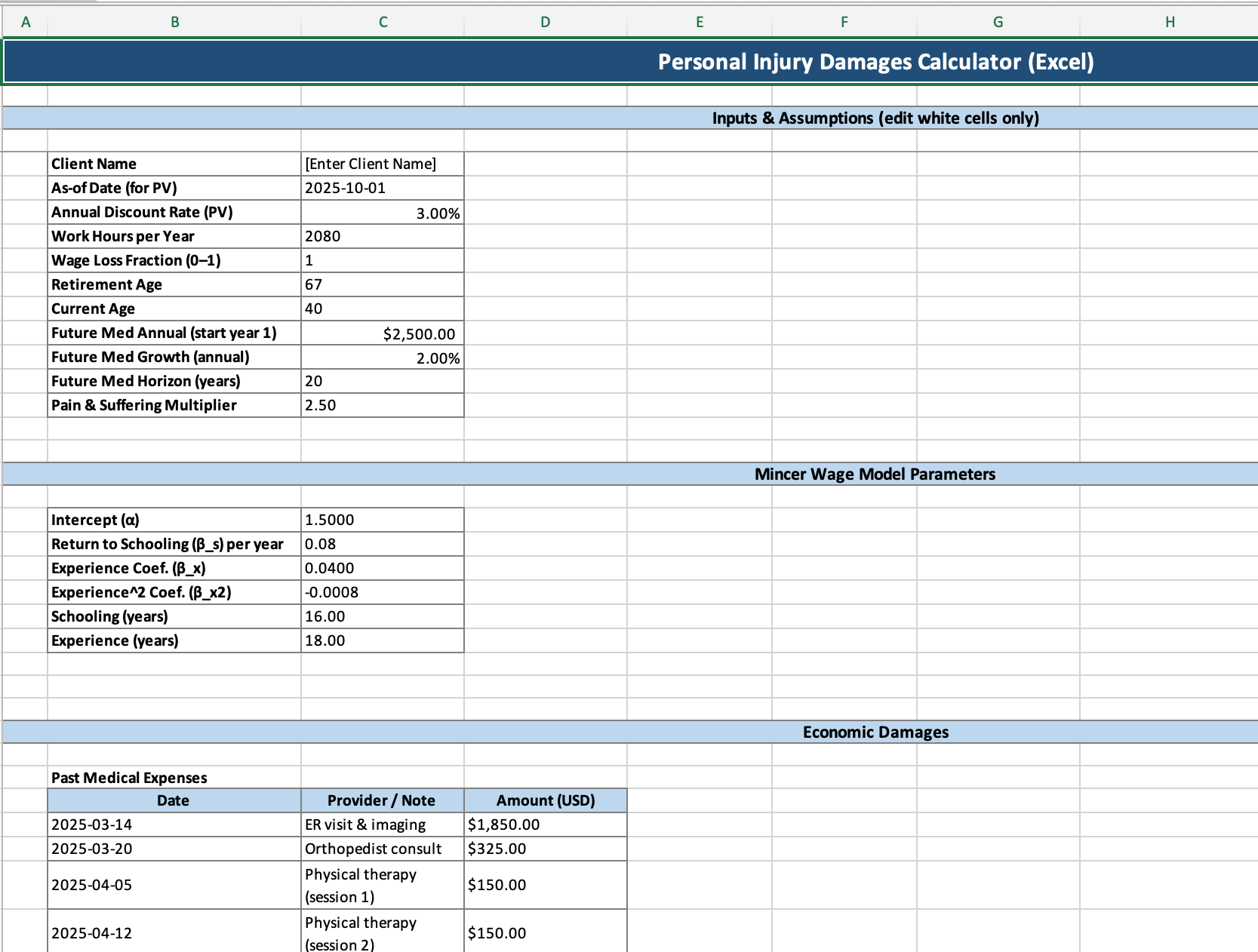

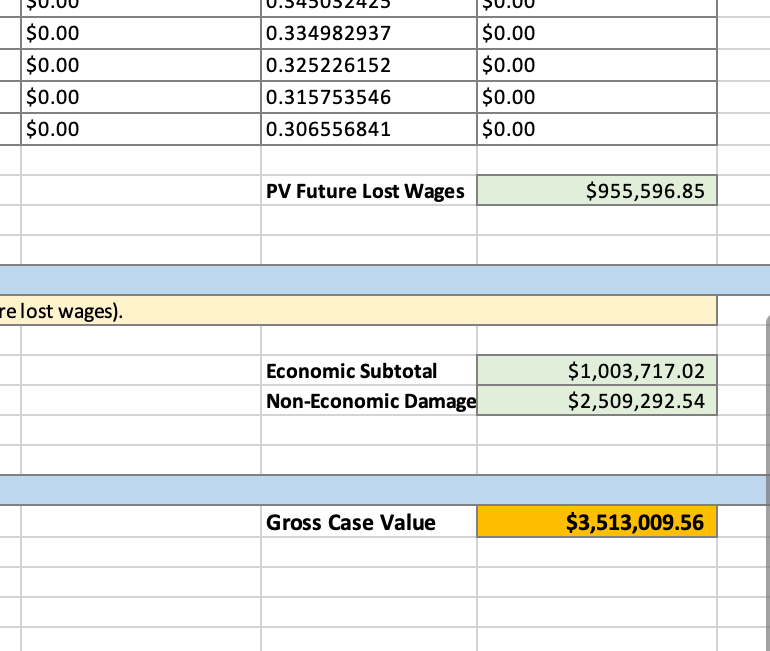

We want to build a personal injury calculator for lawyers as a sophisticated Excel spreadsheet. Here are some features it should have. It should use a discount rate (user set) to compute present values. It should use a Mincer model with several user-set parameters to approximate a future wage trajectory.

Automated Calculation & Structure: Live Formulas: The sheet is built with pre-populated, active formulas. As you enter or change numbers for medical bills or lost wages, all the totals and the final case value update automatically.

Logical Organization: The document is clearly divided into three main sections: Economic Damages: Tangible, calculable losses. Non-Economic Damages: Intangible losses like pain and suffering. Total Case Valuation: The final summary of all damages. Detailed Breakdowns: Within Economic Damages, it has distinct sub-sections for Past Medical Expenses, Past Lost Wages, and estimated Future Medical Expenses. User-Friendly Design: Guided Entry: It includes placeholder text (e.g., [Enter Client Name]) and example entries to show you exactly what kind of information to enter and where. Lost Wages Calculator:

You don't have to calculate lost wages separately; you can simply enter the hours missed and the hourly wage, and the sheet calculates the total for you. Pain and Suffering Multiplier: It incorporates a standard multiplier method for calculating non-economic damages and includes a note explaining how it works. You can easily change the multiplier (e.g., from 2.5 to 3) to see different valuation scenarios. Professional Formatting: Clean Layout: The script automatically adjusts column widths, merges cells for headers, and aligns text for a clean, professional appearance.

Color Coding: It uses distinct background colors to highlight major section headers, total rows, and the final "Gross Case Value," making the sheet easy to read and navigate at a glance. Currency Formatting: All monetary values are automatically formatted as US dollars (e.g., $5,500.00).

After writing some Python code behind the scenes, ChatGPT produced a downloadable Excel file. I needed one round of iterations to fix errors and get the spreadsheet in an acceptable condition. You can look at the result here.

Here are some screenshots. The big picture point, however, is that, although Claude has a slightly more direct way of producing Excel spreadsheets, ChatGPT is fully competent at the job. Again, you can now use AI to do sophisticated mathematical computations needed in law without having to engage in traditional coding. The result is an Excel tool that requires essentially no learning curve.