Building a virtual law museum: Trump v. CASA

Unveiling the Trump v. CASA Virtual Museum and What It Means for the Future of Legal Education

What do we professors do now? This question should be on the minds of many in legal education as AI expands its capabilities at a remarkable pace. The answer, it turns out, might lie in a collaboration between human expertise and artificial intelligence—one that could lower the cost of creating sophisticated educational resources while maintaining the rigor and depth that legal education demands.

The Trump v. CASA virtual law museum I unveil in this blog entry is an example of what is possible. What traditionally would have required months of development, substantial institutional budgets, and teams of web developers was instead completed in a day's work through a human-AI collaboration model. The result is not merely a website, but a digital environment that presents a landmark Supreme Court case as an explorable, interactive educational experience.

The Constitutional Moment That Invited Innovation

Trump v. CASA arrived at a moment of constitutional significance that posed a challenge for traditional teaching methods. Here was a 6-3 Supreme Court decision that ended universal injunctions, reshaped federal litigation strategy, and extended the Court's historical formalism from substantive constitutional interpretation to the traditionally flexible domain of equity. Justice Barrett's majority opinion represented what we might call the "Bruen-ization of Equity"—freezing federal equitable powerto 1789 practices in a move that will reverberate through public interest litigation and federal courts for decades.

How does one teach such a case? Traditional casebook treatment would offer perhaps five pages of excerpts, maybe a few notes on historical context, and leave students to puzzle out the broader implications. That's not so terrible in the same way that it wouldn't be so terrible if kids could learn about dinosaurs only be reading books and not have access to a museum. But just as a physical museum can help structure the experience and leverage the expertise of curators, so too with virtual museums. And what I want to show here is that virtual museums in law are eminently possible.

The Architecture of Understanding

The museum's structure reflects an insight about how legal education can work in the digital age. Rather than forcing students through a linear progression of materials, visitors can wander through interconnected "galleries," each designed to illuminate different dimensions of the decision. The Supreme Court Opinions Wing provides individual galleries for each justice's contribution, offering both basic analyses and in-depth legal analyses that confront broader issues of constitutional interpretation.

Justice Barrett's gallery features both foundational analysis and an exploration titled "The Bruen-ization of Equity," revealing how her historical formalism represents a significant shift in remedial jurisprudence.

Justice Thomas's exhibit warns against the "complete relief" trap, while Justice Alito's focuses on potential loopholes through state third-party standing. The dissenting voices receive similar attention—Justice Sotomayor's gallery examines her citations to Pierce and Barnette as examples of universal relief in effect, while Justice Jackson's explores her concerns about creating "zones of lawlessness."

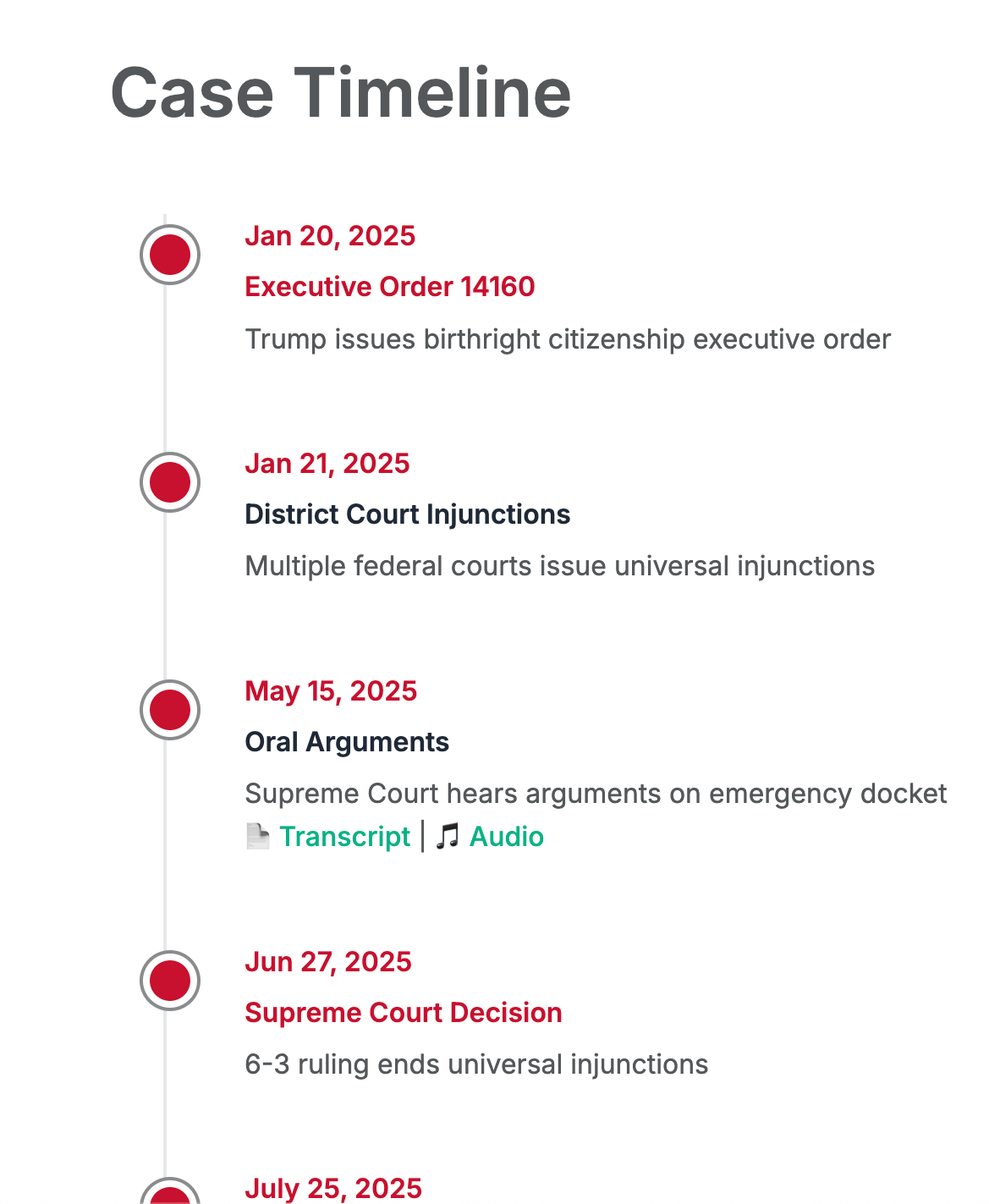

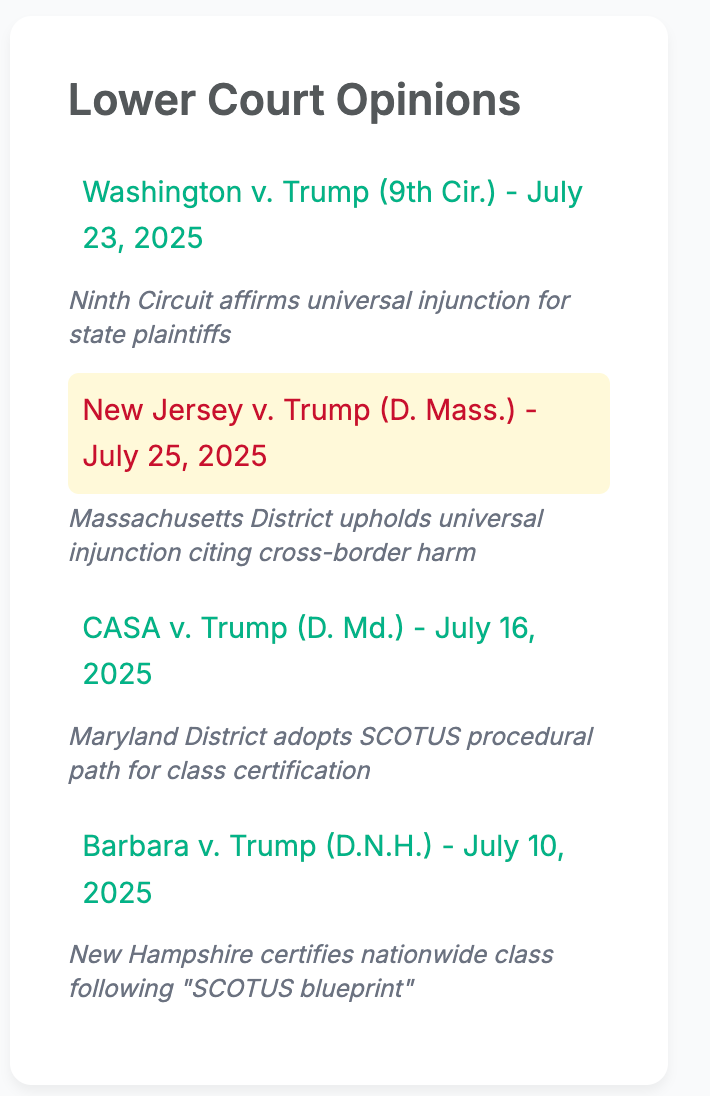

The Timeline Hall traces the case's progression from Executive Order 14160 through the Supreme Court's June 27, 2025 decision and beyond, documenting how federal judges immediately found workarounds—the Ninth Circuit affirming universal injunctions for state plaintiffs, District Courts upholding universal relief citing cross-border harm, New Hampshire certifying nationwide classes. This is not just historical documentation; it's a way of capturing the real-time evolution of doctrine.

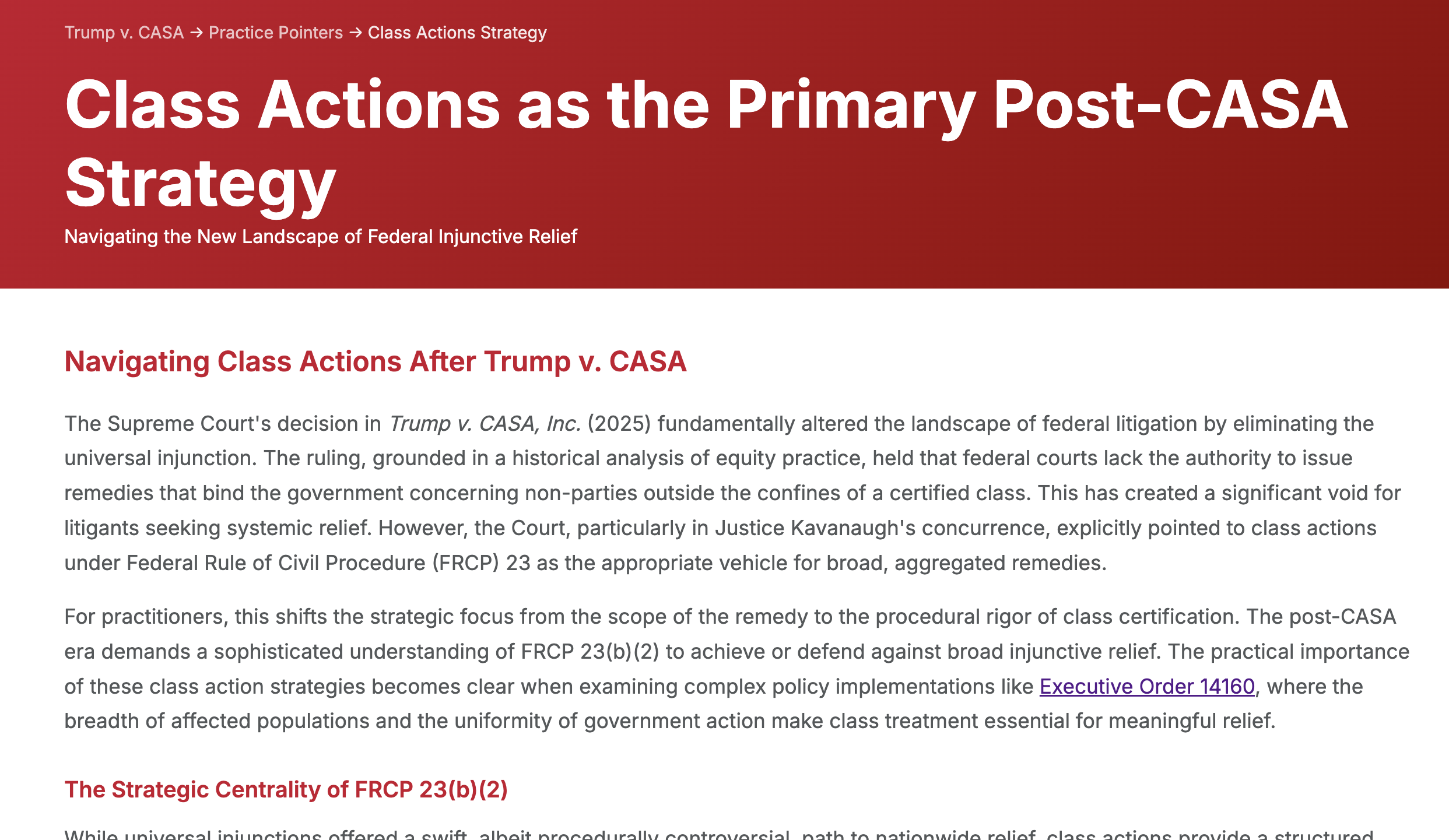

The Practice Pointers Laboratory alone would have been a substantial project using traditional methods. It provides analysis of how FRCP 23(b)(2) has become a primary vehicle for systemic litigation, explains the narrow path remaining for broad remedial relief, and examines how APA vacatur may become a potent tool for nationwide relief against unlawful agency action. This section offers detailed strategic guidance that practicing attorneys can implement.

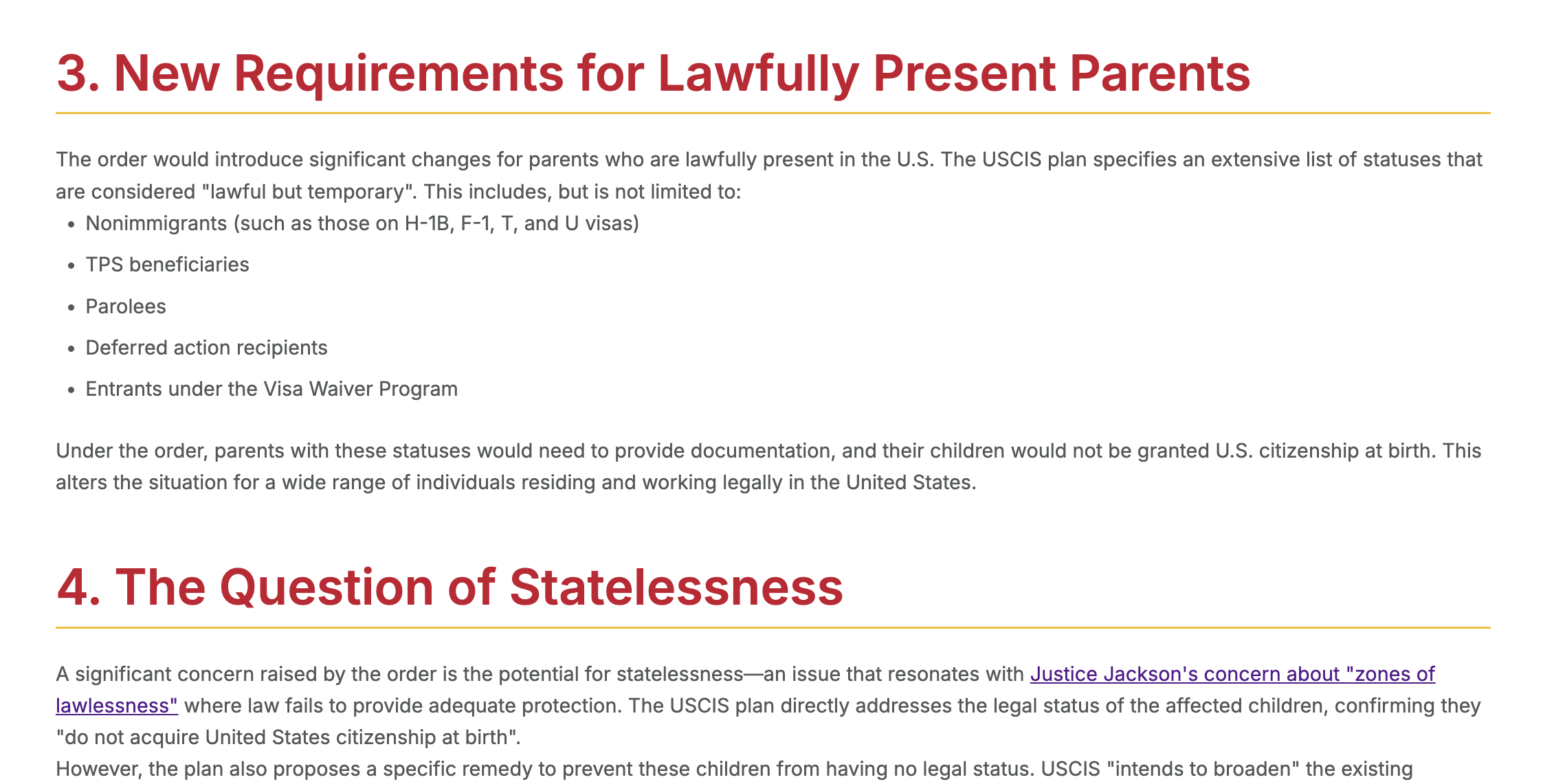

The Human Impact Observatory connects legal doctrine to practical consequences, analyzing how Executive Order 14160's implementation would create a new class of U.S.-born individuals holding temporary, derivative immigration status rather than citizenship. This reflects Justice Jackson's concerns about "zones of lawlessness" while demonstrating how abstract legal principles translate into concrete human experiences.

We've included synthetic educational content that's clearly marked as such: a fictional dialogue between leading faculty experts that provides accessible entry points for complex legal concepts, and a 17-minute podcast that summarizes the case's key elements. These represent experiments in what we might call "educational AI"—content specifically designed to complement rather than replace human instruction.

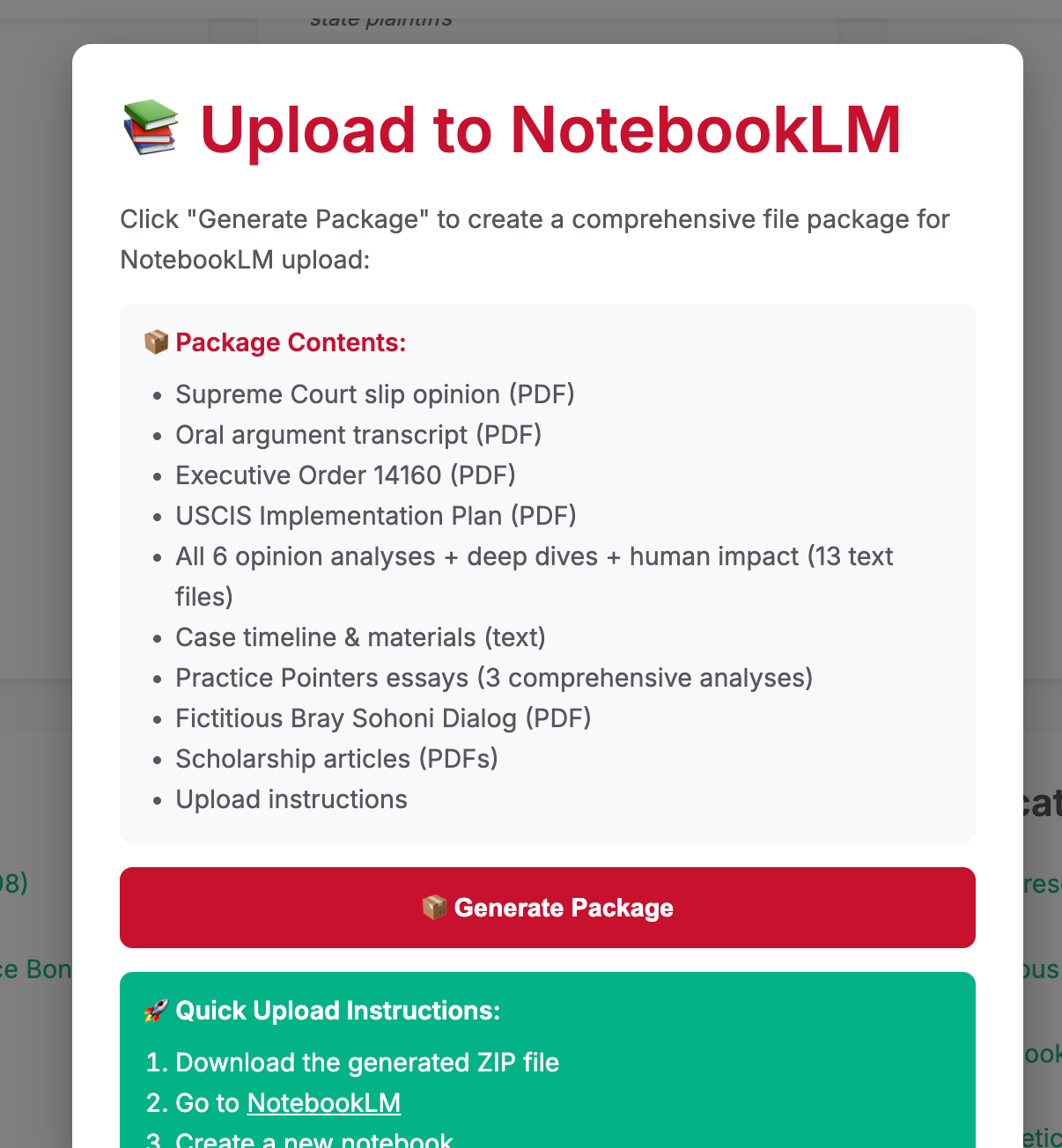

The museum integrates several tools of modern digital architecture. Search functionality allows users to navigate the entire collection efficiently. Mobile responsiveness ensures accessibility across devices. The NotebookLM integration means users can extend their research directly from the museum's collection—essentially creating personalized research assistants trained on the museum's comprehensive materials. It's like a traditional museum being able to give specimen replicas to a visitor that they can then take home and feed into a scientific tool, including ones based on AI, for further research. We thus avoid reinventing every AI wheel and instead piggyback on the outstanding tools one of the world's largest companies (Google) has generally made available.

Methodology

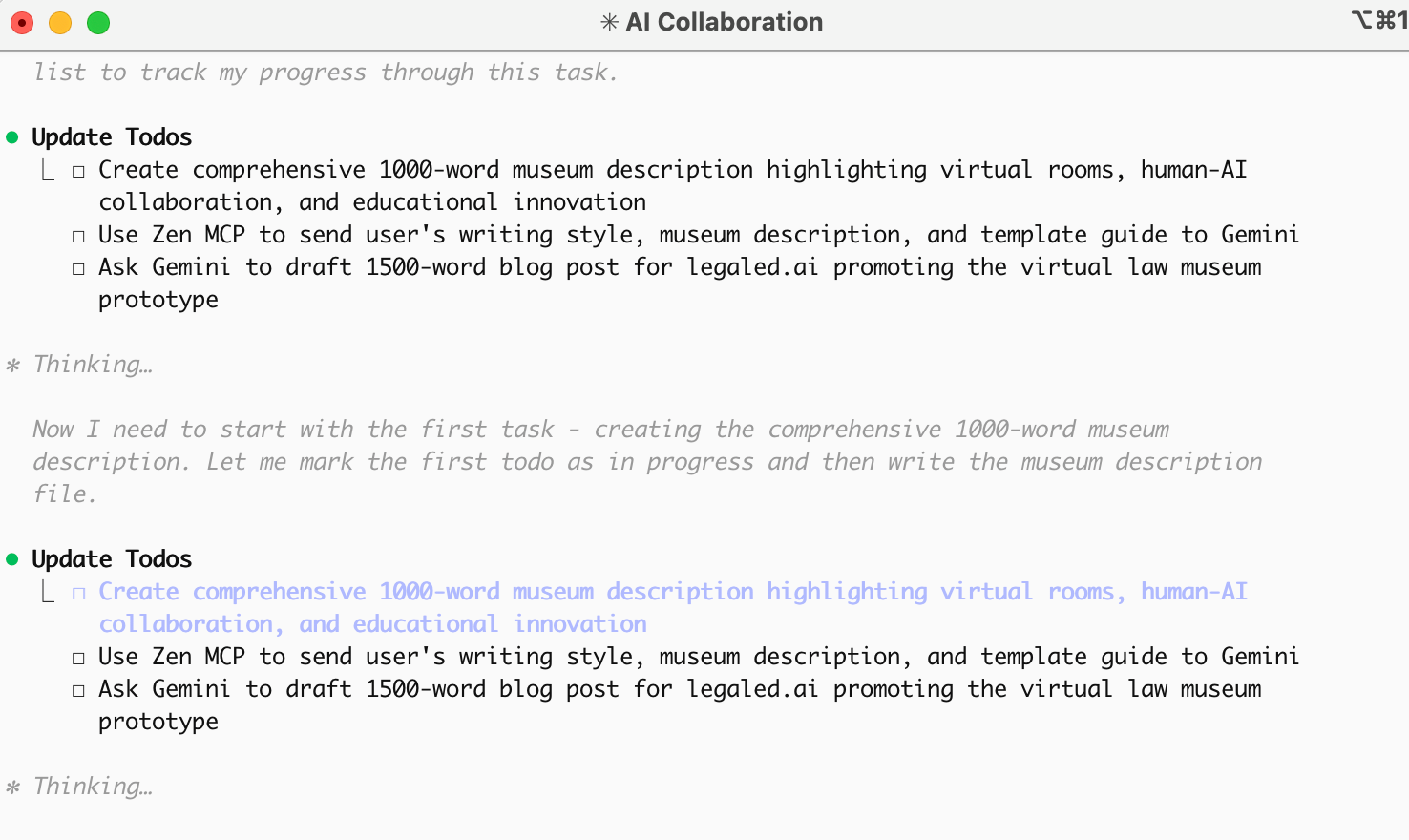

A key feature of this model is the collaboration between human legal expertise and AI analytical capacity. I provided the interpretive framework and strategic focus while a suite of AI tools generated initial content that was then refined through iterative expert review. Neither the human expert nor the AIs could have created this resource independently. Indeed, a human expert and a single AI acting alone could not have done the job either. It took a village (of AIs).

I served as the expert curator and editor, providing legal expertise, analytical frameworks, and quality control. Claude Code acted as the web architect, creating the technical infrastructure and user experience design. Gemini, sometimes acting under my direct supervision, and sometimes under indirect supervision mediated by an MCP server directed by Claude Code provided core legal analysis. It generating initial content that was then refined through review by me and ChatGPT instructed to be skeptical. Grok chipped in on occasion as well when the other AIs were busy or when I wanted a different perspective. This partnership created a resource that none of us could have produced independently—a testament to the power of intelligent collaboration.

Lowering the Barriers to Educational Excellence

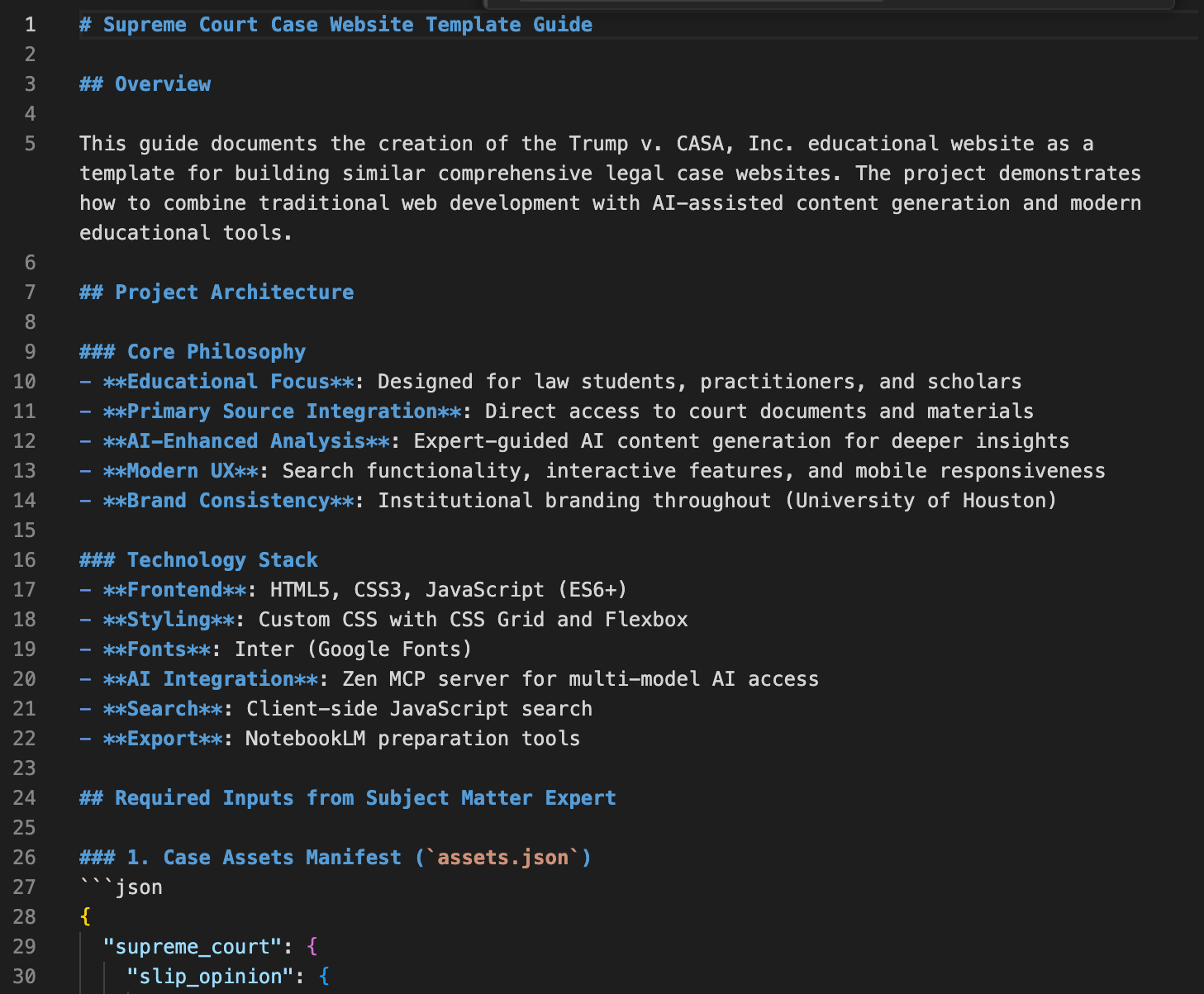

The economics of this model are also noteworthy for legal educators. What traditionally might require months of development and substantial institutional resources was completed in ten hours. It depends how you amortize my (excessive) subscriptions to various AI providers, but any way you look at it the budget to construct the museum was under $100 (omitting my invaluable time). Now that I am up the learning curve – and can teach others how to do this – the costs of construction are even less. I've started on a production blueprint (shown below).

This virtual museum thus serves as more than a case study; it represents a proof-of-concept for a new approach to legal education that significantly reduces the barriers to creating comprehensive, engaging educational resources. The implications are significant. Where traditional case study development might require months of work and institutional resources, this human-AI collaboration model enables legal educators to create sophisticated, interactive learning environments in a fraction of the time and cost.

The model preserves what's essential about legal education—expert judgment, interpretive sophistication, and commitment to accuracy—while leveraging AI's capacity for content generation, technical implementation, and scalability. The result is an educational resource that maintain scholarly rigor while achieving high levels of efficiency.

The Meta-Commentary on Process

Let's be honest. I can't be certain whether this virtual museum represents a future component of legal education or merely an interesting experiment motivated by an upcoming CLE at which I am supposed to teach Trump v. CASA. What I do know is that the process of creating this museum has fundamentally changed how I think about the relationship between expertise and technology in educational contexts.

The human expertise remains irreplaceable—providing domain knowledge, interpretive judgment, quality assurance, and the kind of strategic thinking that distinguishes legal analysis from mere information aggregation. But AI provides something equally valuable: the ability to operationalize that expertise at scale, creating comprehensive educational environments that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

The virtual museum represents my current choice: to embrace the potential of human-AI collaboration while maintaining the standards and rigor that define legal education at its best. As legal education faces increasing pressure to innovate while controlling costs, this collaborative model offers a path forward that preserves academic integrity while embracing technological possibilities.

This shift in creating educational resources is underway. The question for educators is how to best engage with it.

🤖 This blog post was created through human-AI collaboration, demonstrating the same innovative approach that produced the virtual law museum itself. Can you even tell which components I wrote and which were outscourced to an AI trained on my style? Does it matter?

One more thing

As it happened, I picked a very controversial – some would say abhorrent – case for the first museum. I did so, frankly, because my dean asked me to talk about the case at a CLE, I had to learn it anyway for my constitutional law class, and I thought it was rich enough to support a good museum. There are museums throughout the world that deal with extremely unpleasant events. I don't believe that presentation is even close to celebration. As I tell my students, in law we deal with the real world.

Sponsor a wing

You might like the museum but feel it is missing something. Drop me a line and suggest an addition. Construction costs at the museum are generally low. Maybe we'll even name the new wing after you. Or, if you spot a problem with an exhibit, let me know. aiforlegaled at gmail dot com.