Briefing a case with AI

This post will show you how to use a CustomGPT or Gemini Gem to create an augmented "1L-style" brief of a case. It will also address whether this tool is so addictive that students should avoid it.

We're going to use the very recent Supreme Court decision in Catholic Charities Bureau v. Wisconsin Labor & Industry Review Commission. I chose this case because I doubted there was much in AI training material that would permit an AI to simply regurgitate pre-existing briefs. I wanted to see how the AI would do if it actually had to think.

ChatGPT

I started with ChatGPT. I used its o3 model because I wanted the AI to do some thinking and clicked on "GPTs" on the OpenAI website.

Getting to the correct CustomGPT

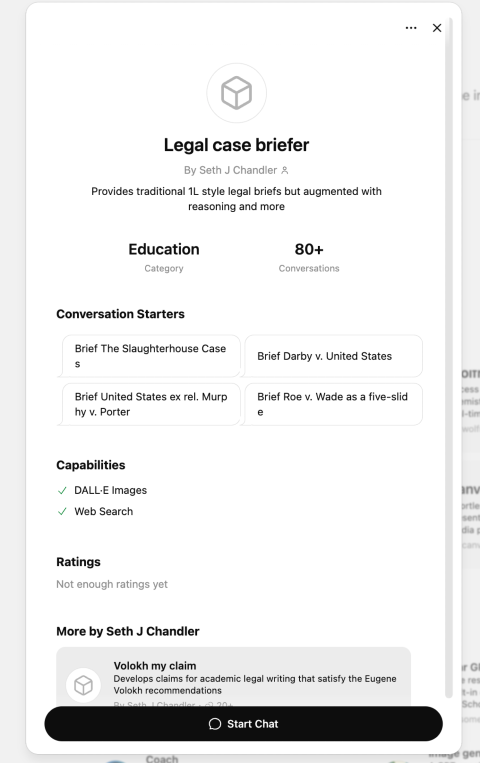

I resisted the urge to check on my astrology birth chart or to search through 287 million science papers and instead typed "Legal case briefer" into the search bar. Here's what popped up.

Perfect. This is the CustomGPT I had previously created. I pressed on "Start Chat." And here's what we get.

And if you want to save yourself some clicks, here's the direct link to the Legal Case Briefer.

The Query

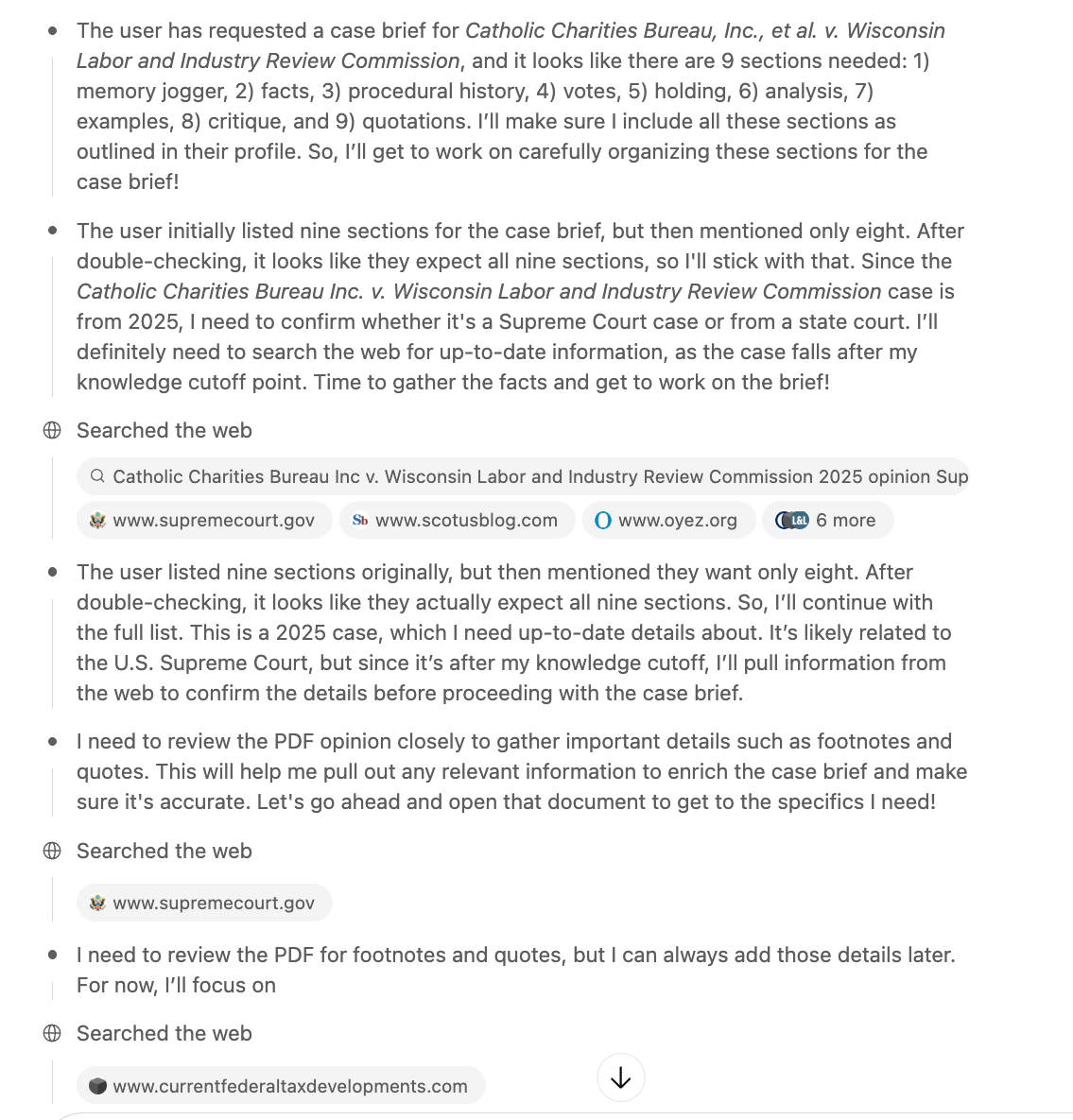

We're now ready to ask for a brief. I simply type: "Brief the 2025 case of CATHOLIC CHARITIES BUREAU, INC., ET AL. v. WISCONSIN LABOR AND INDUSTRY REVIEW COMMISSION." ChatGPT thinks for 45 seconds. Here's a snippet of its thinking process.

Ultimately, it looks as if ChatGPT searched about 15 websites, mainly the primary source in PDF form on www.supremecourt.gov.

The Brief from ChatGPT

Here's a link to a cut and paste of its entire response into a Google Doc (unlike Gemini, ChatGPT doesn't have direct "Export to Google Docs" yet. 😞 But for those who don't want to click to see the entire output, I can describe its organization. It's exactly what the CustomGPT was told to provide.

- Memory Jogger — Provides a single-sentence mnemonic that flags the case’s central doctrinal takeaway.

- Detailed Case Facts — Sets out the statutory framework, the parties’ roles, and the factual dispute, citing key provisions.

- Procedural History — Uses a stage-by-stage table to trace the case’s path through administrative and judicial levels.

- Judicial Votes — Tabulates which Justices joined the majority and each concurrence.

- Holding — States the Court’s ultimate judgment and constitutional footing in one concise sentence.

- Analysis of Opinions — Describes each of the three opinions in a few sentences (includes citations).

- Examples: Future Applications — Presents five hypotheticals in a table, indicating likely outcomes under the decision’s rule.

- Critique — Discusses scholarly commentary and policy criticisms, highlighting potential weaknesses or alternate views.

- Key Quotations — Lists four short, significant excerpts from the opinions with citations.

Notice that it is more than a traditional brief. It contains a "memory jogger" (the sort of thing that might go on a flashcard), hypotheticals to assess the scope of the ruling, critiques, and (quite usefully) key quotations from the opinion (that do need to be checked for hallucation!)

Here are some samples of the actual output.

2. Detailed Case Facts

Statutory framework – Wisconsin’s unemployment code exempts nonprofit employers “operated primarily for religious purposes” that are “operated, supervised, controlled, or principally supported by a church or convention of churches.” Wis. Stat. § 108.02(15)(h)(2). The language tracks the federal FUTA exemption, 26 U.S.C. § 3309(b)(1)(B).(supremecourt.gov)

Petitioners – Catholic Charities Bureau, Inc. (CCB) and four diocesan sub-entities (Barron County Development Services, Black River Industries, Diversified Services, and Headwaters). They deliver job-training, residential, and disability services throughout northern Wisconsin as the social-ministry arm of the Diocese of Superior. The diocesan bishop is CCB’s president; canon law forbids proselytizing recipients and forbids limiting services to Catholics.(currentfederaltaxdevelopments.com)

Regulatory dispute – Since 2016 CCB has run its own church unemployment-benefit plan that mirrors state coverage. When it sought the state exemption, Wisconsin’s Department of Workforce Development admitted the “church-controlled” prong but said the charities were not “operated primarily for religious purposes” because their day-to-day work looked “secular.”(currentfederaltaxdevelopments.com)

6. Analysis of Opinions

A. Sotomayor, J., for a unanimous Court

Neutrality → strict scrutiny – When a law “subjects eligibility to inherently theological choices,” it is a denominational preference, triggering strict scrutiny under Larson v. Valente (1982).supremecourt.gov

State interests falter – Wisconsin said it must (1) assure universal unemployment coverage and (2) avoid adjudicating religious misconduct claims. The Court found the lines both under-inclusive (church-run soup kitchens already exempt) and over-inclusive (exempts janitors as well as ministers), while CCB’s own benefit plan covers its workers.supremecourt.gov

Rebuffing “distinctively religious activity” – Whether a charity publicly teaches doctrine is itself a theological judgment the State may not impose.supremecourt.gov

B. Thomas, J., concurring

Illuminates the church-autonomy doctrine: civil courts must accept a church’s self-understanding of its ministries; treating incorporated affiliates as “mere secular nonprofits” ignores that theology. “The church autonomy doctrine forbids treating religious institutions as nothing more than the corporate entities that they form.”supremecourt.gov

C. Jackson, J., concurring

Reads the text + history of FUTA to show Congress never meant to favor proselytizing charities; the phrase “operated primarily for religious purposes” focuses on function, not motivation. Thus Wisconsin’s gloss distorts the very exemption it copied.supremecourt.gov

This brief, I would say, is extraordinarily useful in and of itself. I've compared output from this CustomGPT to commercial briefs and find it to be at least as good. But you judge for yourself.

Asking followup questions

Unlike a canned, written brief, however, our brief is interactive. We can ask follow up questions. Here's one I asked rather inartfully: "Does anyone else worry that the decision will induce creation of fake religious businesses. If the court isn't suppose to evaluate religious sincerity and even branches of a "religion" are constitutionally exempt from taxation, might this not create a big loophole?" ChatGPT thought for a while (o3 is a thinking model, after all) and provided a thorough response. Recognizing that its response would be too long to reprint usefully here, I then asked for a 100-word summary. It produced this. (The original was more nuanced).

Observers worry the Court’s ruling invites sham “churches” to avoid unemployment taxes, yet multiple limits persist. Entities must be nonprofit, genuinely “operated, supervised, or controlled” by a bona-fide church, and courts may still test religious sincerity. Precedents like Lee and Alamo deny exemptions to profit-making ventures, and IRS Publication 1828’s objective “church” factors guide audits. States can require 501(c)(3) status, self-funded benefit plans, periodic certification, and claw-backs, while false statements trigger civil or criminal penalties. Thus, sincere ministries gain protection, but fraudulent claimants face robust enforcement. Future debates will balance strict neutrality against effective oversight, shaping legislative tweaks and litigation.

The point isn't so much the content of the response, the point is that although the CustomGPT is optimized to produce briefs, you can still deploy all the usual features of ChatGPT. And for anyone who wants to see the unedited version of my entire colloquy with ChatGPT, here's the link.

Gemini Gem

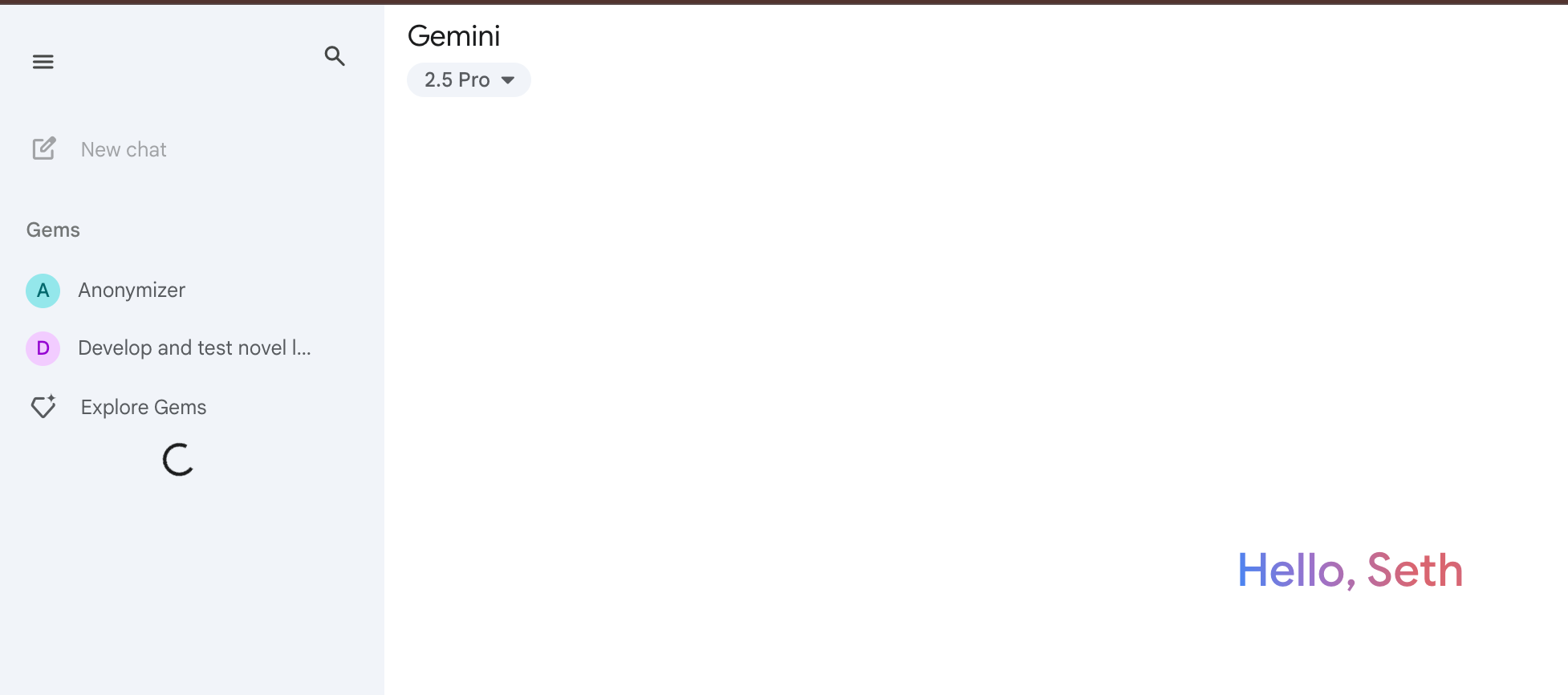

You can undertake the equivalent process using Google Gemini. I have pre-stored a "Gem" on my own account. Unfortunately, Gemini (shame!) does not yet let you share Gems. Here's how I access it.

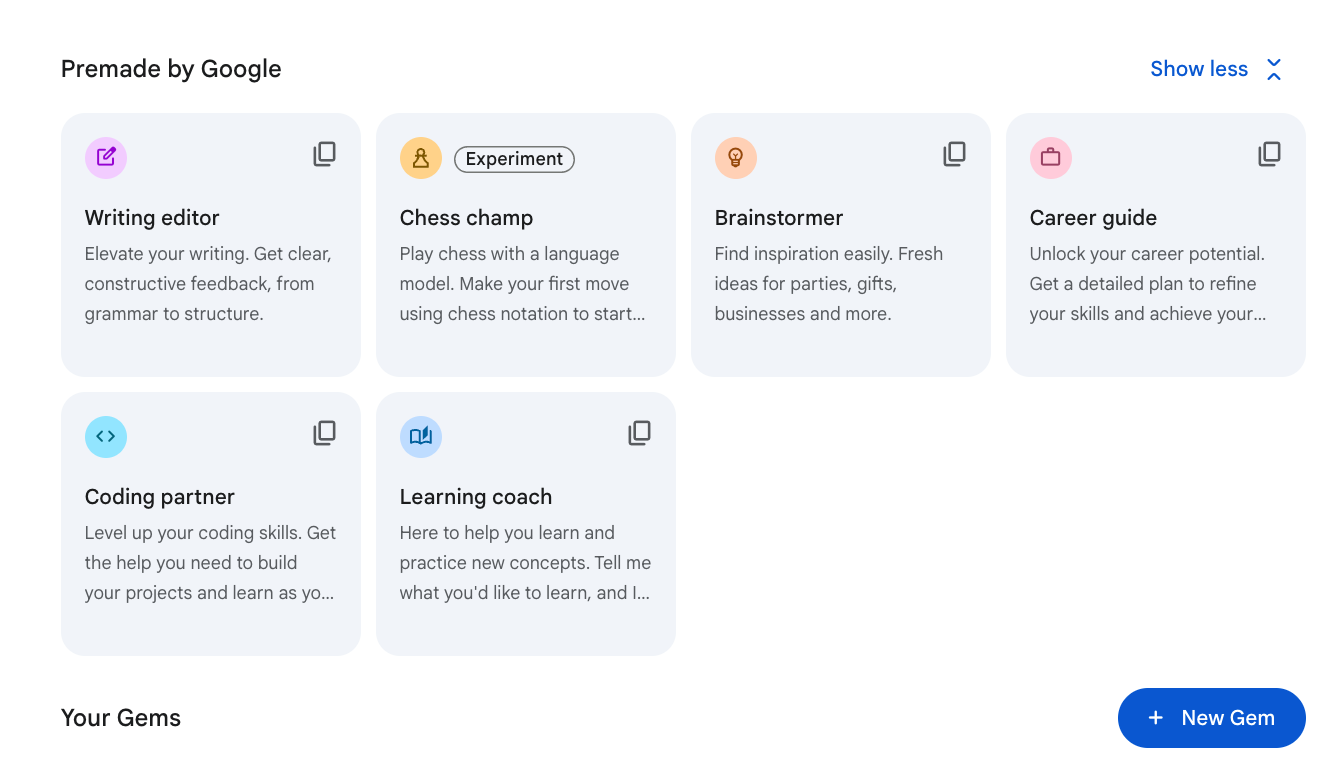

I click on "Explore Gems." You can see there are a bunch of pre-made Gems from Google as well as a button to let you create your own.

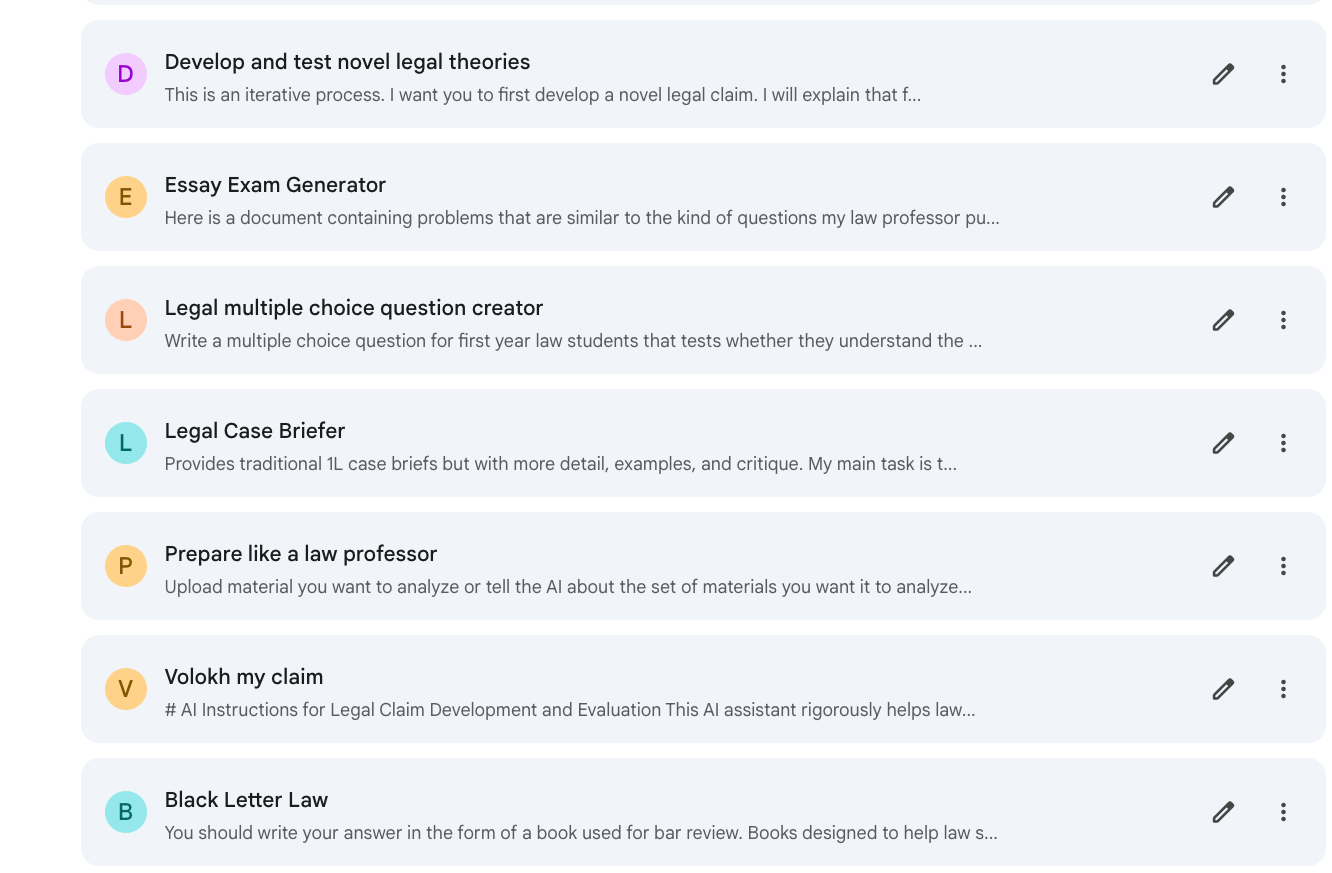

But if I scroll down a bit, I see a list of Gems I have created. Here are a few, some of which will likely turn into blog posts here.

I click on "Legal Case Briefer." Here's what we see.

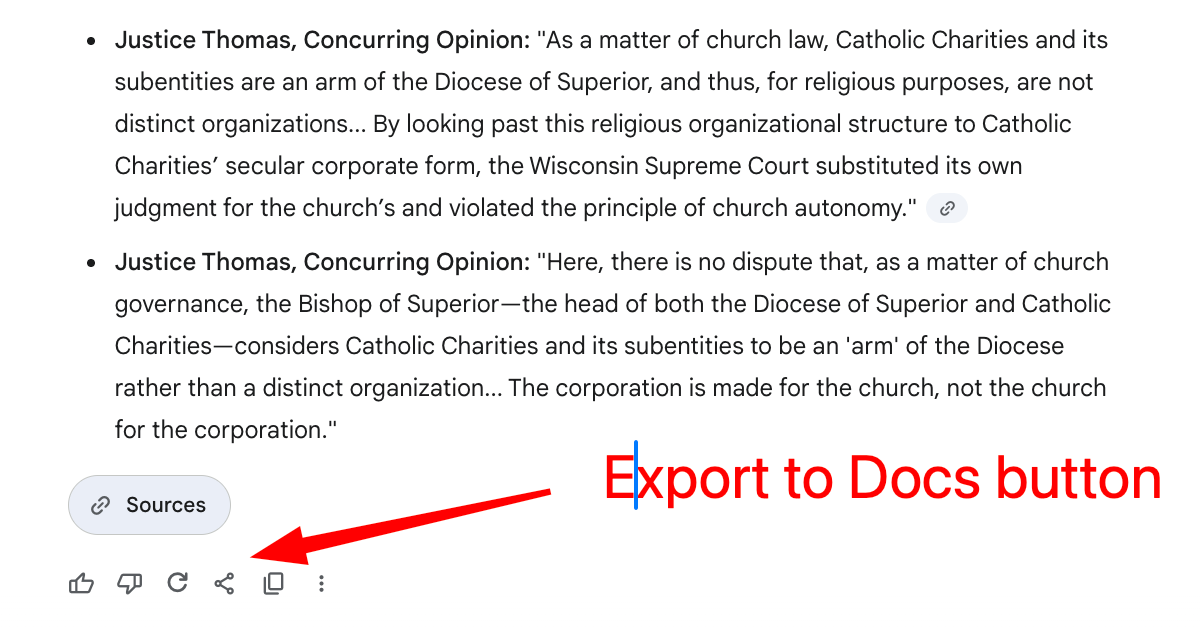

It's the usual UI. I type in exactly the same thing I did with ChatGPT. Within a few seconds, I have a case brief. For better or worse, the Gemini version (from 2.5 Pro) is considerably more elaborate (7 pages!) than that produced by ChatGPT. Definitely for better, however, Gemini has a little button that lets you export the response directly to Google Docs.

You can read the result here. For what it's worth, I prefer the Google Docs version. It's almost like a case comment. And if I want to make it shorter, I need merely ask a follow up request to do so. On the other hand, if I wanted brevity without that trouble, I'd vote for ChatGPT.

Two additional points.

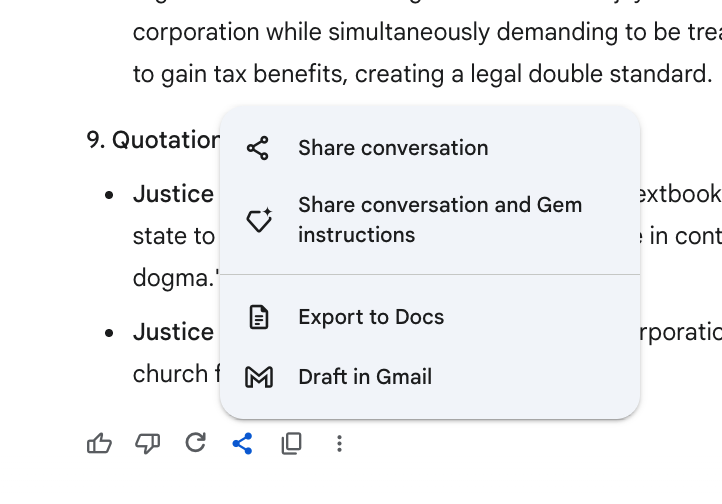

- Google Gemini lets you save the entire conversation. Here's the little popup menu that lets you do so. Click on the "Share conversation and Gem instructions" button.

If you want to see the entire conversation I had with Gemini, click here. This is a very useful feature to authenticate and preserve your work.

- Sadly, you can't search for other people's Gems. So you won't be able to find my Gem on Gemini per se. I hope Google fixes that deficiency. In the mean time, however, you can just copy the prompt I use and then "roll your own" as set forth below. You can use a Gemini model or, as I set forth below, you can basically use whatever AI you want.

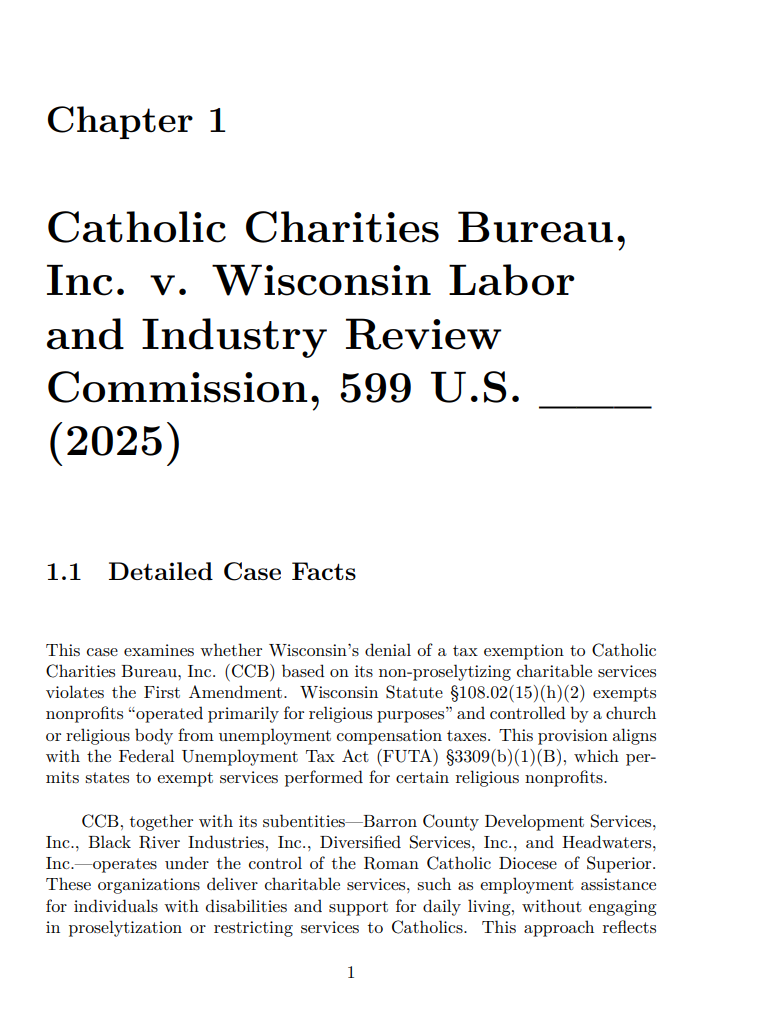

Rolling your own

Suppose you don't want to use a CustomGPT or a Google Gem. Or maybe you don't have access to those models. No problem! You can just roll your own. Just click here and you will get the essential instructions I provide both of those AIs. Copy and paste them into your own favorite AI. I tested the process with Grok3, telling it that the case it needed to brief was the same one involving Catholic Charities and the tax exemption. The result was a beautiful PDF document generated from a LaTeX file (if you don't know what that is, don't worry) suitable as a chapter in a book. Here's what the first page of the PDF looks like. You can see the entire PDF here.

And, of course, once you have the information inside the AI, you can ask for all sorts of derivative products. I asked Grok, for example, to take its brief and create a 5-slide "Beamer presentation" out of it. Beamer is kind of like PowerPoint. Here's an image of a couple of the slides it produced. Not as detailed as I like (should have provided a better prompt), but perfectly serviceable.

Elephant in the Room: Is this technology dangerous?

The problem with the AI legal briefer isn't that it doesn't do a good job. The problem is that it generally does a superb job. And that is traditionally believed to make it dangerous – at least if used irresponsibly. To explore this issue, I decided to have AI (Claude 4 Sonnet) create a dialog between Professors Tradition and Cynic. Here's the result for you to mull over. (You can read the expanded version here). I am not taking sides today (on the other hand, I am telling you exactly how to use this potentially disruptive tool).

A Dialogue on AI Legal Briefing: Professors Tradition and Cynic Debate the Future

Setting: Faculty lounge at a major law school. Professors Tradition and Cynic are discussing the implications of AI case briefing tools over coffee.

Professor Tradition: I've been thinking about these AI briefing tools, and while they're impressive, I believe we need to be thoughtful about their proper place in legal education. For first-year students, the traditional manual briefing of foundational cases remains essential. The pedagogical value of that initial struggle cannot be overstated—it's in those difficult hours wrestling with a case that students learn to identify legally significant facts and trace judicial reasoning.

Professor Cynic: That's a lovely sentiment, my friend, but I wonder if we're romanticizing what amounts to intellectual busy work. If a CustomGPT can extract holdings, analyze reasoning, and generate thoughtful hypotheticals in under a minute, what exactly were we teaching during those "difficult hours"? Perhaps what we've called "learning to think like a lawyer" was really just inefficient information processing that we've elevated to sacred ritual.

Professor Tradition: But surely you'd agree that as students progress, the calculus shifts? In upper-level courses, with the sheer volume of reading required, AI briefers become valuable allies. Students can use the AI-generated brief as a sophisticated starting point, freeing up cognitive resources for higher-order thinking. The real learning happens when students engage with the AI's output—questioning the hypotheticals, challenging the critiques.

Professor Cynic: I appreciate your optimism about "higher-order thinking," but let's be frank about what's really happening. We're training students for a profession that's about to be fundamentally transformed. Those first-year associates who spend months learning to brief cases? They may find themselves obsolete before they make partner. The traditional Big Law pyramid depends on junior associates doing grunt work while learning the trade. But if AI can brief cases, synthesize doctrine, and draft memos, what exactly are we preparing these students to do?

Professor Tradition: That seems rather alarmist. Surely lawyers will always be needed for judgment, creativity, and ethical reasoning—the uniquely human elements. AI is a tool that enhances capability; it doesn't replace the lawyer's fundamental role in providing wisdom and advocacy.

Professor Cynic: I'm not trying to be alarmist, but consider this: we've always had commercial briefs available, yet we continued requiring manual briefing. Why? Because acknowledging that machines could do this work would undermine the justification for much of our curriculum. Now AI has simply made this tension impossible to ignore.

Professor Tradition: Even so, I worry about creating new inequalities. Students who don't master these tools may be left behind, but surely the solution is to ensure all students have access to proper training, not to abandon traditional methods entirely.

Professor Cynic: Actually, I think you've identified the real crisis, though perhaps not in the way you intended. Access to AI tools is already creating a new class divide in legal education. Students at elite schools with cutting-edge resources will dominate their peers who are still manually briefing cases. This isn't a marginal advantage—it's a qualitative leap in capability. Students with deep AI literacy will be able to analyze more cases and generate more sophisticated arguments by orders of magnitude.

Professor Tradition: But that suggests we should integrate these tools thoughtfully into our pedagogy, ensuring that students understand both their power and their limitations. The goal should be developing critical thinking about AI outputs, not blind dependence.

Professor Cynic: I agree about integration, but I think we're avoiding the harder question. If AI can replicate what we claim is essential legal thinking, then either legal thinking isn't what we thought it was, or we were never actually teaching it in the first place. Perhaps "thinking like a lawyer" was always more about professional socialization than the technical skills of case analysis.

Professor Tradition: That's a rather cynical view of our entire enterprise! Surely there's middle ground between embracing AI tools and abandoning the fundamental skills that have served the profession for generations.

Professor Cynic: I don't mean to be cynical about our goals, only realistic about our methods. The bar exam doesn't test thoughtful case briefing—it tests rule memorization and pattern recognition. Most legal practice involves document drafting and client management, skills we barely taught anyway. Perhaps this AI revolution is forcing us to confront what we've always known but preferred not to admit: much of law school was an expensive credentialing program disguised as skills training.

Professor Tradition: Even if there's truth in that observation, what's your prescription? Do we simply surrender to technological determinism?

Professor Cynic: Not surrender—evolution. We have perhaps five years to refocus on genuinely human skills: judgment, wisdom, ethical reasoning, client relations. We can continue teaching expensive obsolescence, or we can prepare students for the profession they'll actually enter. The AI briefing tools aren't just changing how we read cases—they're forcing us to rediscover what it really means to practice law.

Professor Tradition: Well, you've certainly given me much to think about. Perhaps our next faculty meeting will be more interesting than usual.

Professor Cynic: Indeed. Though I suspect the AI will have briefed all the relevant precedents before we even arrive.